In the first article I attempted to demonstrate, by an appeal to various decisions and documents, that the creeds have always occupied a clearly-defined position within a confessional Reformed church which takes seriously her task of confessing in the world. It was further noted that recent discussions within several of these churches demonstrate the presence of problems in this connection. Specific words and phrases are under fire.

It is therefore not amiss that once again I raise the question: What is the character of the standards of the church? Perhaps I do not express myself too strongly, when I contend that this is a basic, a burning question within the fellowship of the Reformed churches today.

It is an ecumenical question.

During the past summer the Reformed Ecumenical Synod again convened. Its avowed basis is the Holy Scripture of the Old and New Testaments as interpreted by the Reformed confessions. All members of such a synod must give public testimony that they adhere to these confessions.1

It is also a pastoral question.

It may well be asked what will happen when one unites with a congregation of likeminded, confessing believers with a determination to maintain distinctions between “essentials and non-essentials,” between “affirmation and representation” of the truth confessed. What are the rights of the congregation, when such is openly done? What may the congregations expect of pastors who champion such distinctions? Who gives the pastors the right to appeal from the creeds to the Gospel, when these men preach to God’s people who are by no means always in a position to follow the intricate evolutions of recent theological thought?

It is fully as much an ethical question.

What does creedal subscription really mean? If such subscription implies a subjection to the substance but not the words of the creeds, is not thereby the door thrown wide open to an unethical and unallowable reservatio mentalis? Well may everyone who subscribes ask himself the pertinent question; To which creed am I subscribing—my own or that of the church? And should I be subscribing to my own creed, even in the most sincere way possible because therein I hear Christ’s voice, what guarantee is there that I am not disagreeing with the confessing church which has legally called me to be its pastor?

A LESSON FROM HISTORY

Several Dutch Reformed theologians at this point speak of the intent of the confessions. They fail, however, to answer the pressing and prior question: Is it always evident that there exists such an intent of the confession apart from the specific words which have been adopted? Is not the door flung wide open in such cases to individualism and subjectivism, to a degree of latitude in doctrine, perhaps even to a devaluation of Scripture when this idea of the vox humana (the relative historical context and content of human words) comes to be applied to the written Word of God?

We never live in a climate of rein-kultur, a climate of experimenting which would leave our experience unchanged. Our problems—and this deserves to be remembered—are the problems with which former generations also wrestled.

Here history can teach a much-needed lesson. Sometime during the previous century the father of Dutch Modernism wrote his justly famous and significant work on systematics, The Doctrine of the Reformed Church. This man Scholten was an honorable fellow. In harmony with the so-called results of the Biblical sciences of his day he developed a liberal theology. But in all sincerity he called his systematics Reformed! This is apparent from his introduction. “One can conclude from my inquiry how a Reformed minister, faithful to his subscription, can adhere to the doctrine which, in its nature and spirit, is essentially and chiefly the Reformed confession, except for the free development of science; and that it makes quite a difference scrupulously to honor the letter of the creeds or heartily to consent to the spirit and principles of the Reformed Church and to continue building on the evangelical foundation of our fathers.”2 Scholten wanted to be Reformed, Biblical, and confessional. His pupils, as one after another they filled the pulpits of the land, corrupted the Reformation, the Bible and the church confessions.

CREEDS SUBJECTED TO THE SCRIPTURES

All this makes the question most pertinent: What is the character of church confessions?

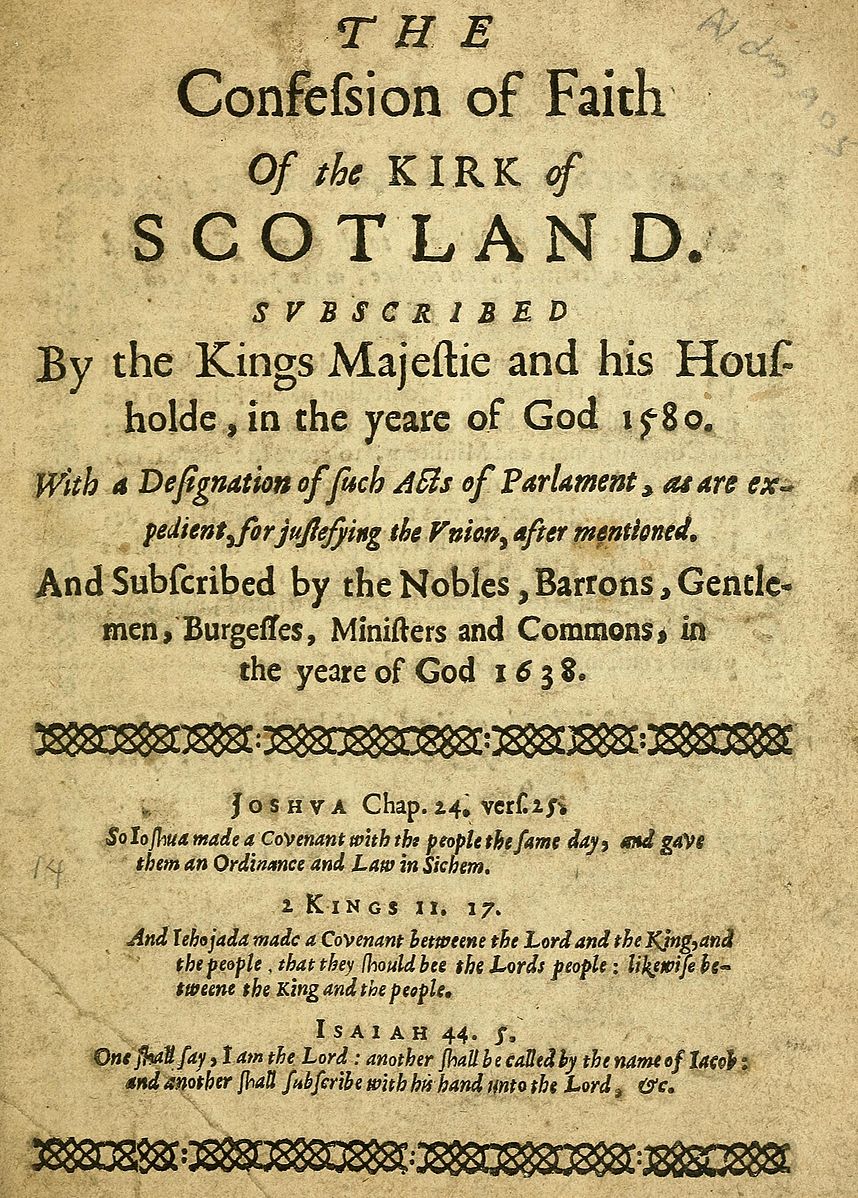

Let us look at one of the oldest creedal statements of the Reformed Churches, the Scottish Confession of 1560. In its preface we read this statement: “If any man will note in this our Confession any article or sentence repugnant to God’s Holy Word, that it would please him of his gentleness and for Christian charity’s sake to admonish us of the same in writing; and we upon our honours and fidelity to God’s grace do promise unto him satisfaction from the mouth of God, that is from His Holy Scriptures, or else reformation of that which shall prove to be amiss.”3 Here the view is plainly stated that a confession should echo God’s Word. A creed therefore is changeable; in fact, it should be changed if anyone can demonstrate that the Gospel is not clearly sounded therein. Such a change must even be called a reformation!

The Arminians in the Netherlands, who deviated in their doctrine of predestination from the Belgic Confession, strongly opposed the binding character of creeds. Their arguments were refuted by the church historian, Trigland, in the following manner: “In which sense should one subscribe to the creeds? Because they agree with the common opinion of all Reformed churches. But suppose your deviating opinion is indeed true and agrees with the Word of God? In that case you are right in this respect and the church is wrong. But in the meantime you cannot be a minister of that church, because it does not recognize as long as it has that confession any other ministers as its own than those who accept its Confession as being in accord with Scripture. If the Reformed churches would change their Confession for another, the situation would be different. But this is not yet the case, because they know that their Confession agrees with the Word of God. If we do not speak in this vein, everything in our churches is un· settled, and all things are rendered free and uncertain.”4

Trigland’s position is illuminating. He stresses that God’s Word alone has final authority. It is possible, too, that the creeds in one or more parts must be changed. Yet so long as this is not done, the church confesses in and through its specific creeds the truth of God’s Word. No one may claim for himself the right to change the words of these creeds or deviate from their evident meaning.

Those within the Reformed community today who wrestle with problems presented to them by the language, expressions or texts quoted in the creeds usually overlook another equally significant problem: that of the community of faith within the church, of the mutual agreement of all members be they scholars or unlearned men, men who are competent to read Kittel’s Theological Dictionary or unable to do so, trained ministers or ordinary housewives. For all without exception the rule stands: our Forms of Unity are standards of the church. They are our common treasure. It is, therefore, an evil thing to speak of their intent apart from the meaning commonly attached to the words which they employ.

REAL AND IMAGINARY PROBLEMS

Are there, then, no real problems left at this point? Is it not a kind of confessionalism to adhere slavishly to the words and expressions of these venerable documents as these stand and are evidently meant?

Should anyone defend the thesis that our creeds are sacrosanct, that in them once-for-all every aspect of the truth of God’s Word has been summarized adequately, I would not hesitate to call him a confessionalist. On the other hand, if there are real problems—and I read so much about this in today’s theological literature—these must be presented and discussed and resolved in the assemblies of the church. This procedure alone does justice to both the church and those who have real difficulties.

Here I believe we should concern ourselves only with real difficulties. There are also imaginary difficulties. Among these must be reckoned objections raised against the language, style and syntax employed in the sixteenth century; to the quantity and quality of the texts quoted in the creeds; to the incompleteness of the creeds resulting from the fact that they do not meet all the needs and fail to challenge all the errors of our day. Who would not heartily agree with men who speak of the desirability of a new creed which could profess the name of our Lord in the language of and according to the needs of our time? How greatly the churches would benefit, if such a creed were framed and adopted.

Real objections are those registered against the evident meaning of words and expressions employed by the creeds. These are inspired by the tension between such words and the Gospel as we have come to understand it. Should such difficulties arise, the only proper road to follow is that prescribed by the Form of Subscription, “We promise that we will neither publicly nor privately propose, teach, or defend the same, until we have first revealed such sentiments to the Consistory, Classis or Synod.”

THE WAY OF THE SPIRIT

Here the task of the confessing church, which is also communion of the saints, begins. Such a true church is not a court of law. Neither are its assemblies a place for endless dialogue. Rather, the true church is the house of prayer where we may confidently expect and experience the presence of the Holy Spirit who leads us into all truth. Asking for the Spirit’s light, the church will find the way which leads into all truth.

At this point several distinct possibilities open up, when these difficulties are properly registered and processed with the ecclesiastical assemblies.

The possibility is very real that by means of brotherly discussion the objections will be removed.

A second possibility which emerges is the possibility of changing the creeds. In such instances advice should be asked of all Reformed churches who hold these confessions in common with us. They are not the private property of one denomination!

A third possibility is that the church will deem it wise to elucidate an expression an her confession by means of an explanatory note.

It may be—and this is a fourth possibility—that the church cannot feel free to change her confession and the objector cannot feel free to change his opinion in the matter, but that synod nevertheless declares that the deviating view, under certain conditions, can be tolerated within the church’s fellowship.

A fifth possibility is that to the church’s mind the objections raised betray such a heretical character, that the person who presented them and persists in them must be disciplined not only because he patently contradicts the confession but because he is at this point disobedient to God’s Word.

This is the way of the well-organized church.

By following this road the church will enjoy the blessing of true fellowship in the common faith so strikingly set forth by St. Paul, “that we no longer be children, tossed to and fro and carried about with every wind of doctrine, by the cunning of men, by their craftiness in deceitful wiles. Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ” (Ephesians 4:14, 15).

1. Rules and Standing Orders of the Reformed Ecumenical Synods, II and IV.

2. J.H. Scholten: De Leer der Hervormde Kerk, 1861; p. vii.

3. Philip Schaff: Creeds of Evangelical Protestant Churches, p. 437.

4. J. Trigland: Kerkelijcke Geschiedenissen, p. 439.