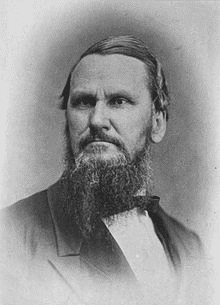

January 1998 marks the 100th anniversary of the death of notable Southern Presbyterian theologian, Robert L. Dabney. Dabney was a lively, zealous and influential churchman of his day, though one often unknown by contemporary Reformed Christians who are not of southern heritage. In the interest of remembering the efforts of Reformed theologians who have preceded us, this article will offer some basic background and analysis of the life and work of Dabney.

THE MAN

Robert L. Dabney was born in 1820 to a fairly well-off and respected family in Virginia. He was raised in the faith in the Presbyterian Church, and received much of his early education at small. local private schools where considerable attention was given to training in the classics. At age 16 he enrolled in Virginia’s Hampden-Sidney College, where he excelled at his studies and completed a great deal of the required work. However, he decided on his own to drop out of school a little more than a year later, due to some financial hardship his widowed mother faced as she tried to manage the family affairs. Approximately his next two years were spent shoring up the family property by means of rigorous agricultural work, though he earned a little money on the side by establishing his own small school and teaching a number of young students.

By late 1839 his mother’s affairs were in good enough shape to convince Dabney that it was time to return to school. Instead of heading back to Hampden-Sidney, he decided to attend the venerable University of Virginia. He remained there for about two and a half years, and received a well-rounded education for which he would express great appreciation in later years. He graduated with the M.A. degree (no prior bachelor’s degree was required). Following this, Dabney spent two more years working on his mother’s farm and teaching at his school. It was apparently some time during this interval that he committed himself to pursuing the ministry, and in November of 1844 he matriculated at Union Seminary in the town of Hampden-Sidney, a Presbyterian school primarily serving the states of Virginia and North Carolina. Dabney seems to have been something of a legend as a student at Union. He finished his studies in just two-thirds of the usual time, while reading and writing extensively on his own and even doing voluntary maintenance work around the seminary grounds as a form of exercise.

Soon after finishing seminary, Dabney was ordained and sent off as a home missionary to serve in a large, sparsely-populated part of Virginia. After riding circuit for about a year, he received a call to pastor a rather large, established church in his home state, a call he accepted and pursued until 1853. During this tenure as pastor, Dabney married Lavinia Morrison, with whom he eventually had five children. Dabney also pursued the life of a part-time scholar while he pastored, and his writings which began to appear regularly in religious journals caught the attention of some of the leaders among the Virginia Presbyterians. The result was a call to teach church history at his alma mater, Union Seminary, a call which he accepted with apparently some hesitation. After teaching in this field for six years, he was elected professor of systematic and polemic theology, a position considered to be of more importance than that of church history. He remained at Union teaching theology for nearly twenty-five more years, during which time he built up a reputation as one of the leading Reformed theologians of his day. Certainly he was one of the most influential, judged by the large number of future pastors he trained at the Seminary and by the rather enormous amount of writing which he published.

Dabney’s days teaching at Union Seminary were not ones of scholarly repose. Within a couple years of being appointed to teach systematic theology, Dabney saw his beloved Virginia invaded by the Northern armies. Dabney had earnestly hoped that the federal union could be preserved, and believed South Carolina extremely foolish for seceding when it did, but he was enraged by what he perceived as an unwarranted response by President Lincoln and other Yankee leaders. Thus, Dabney stood entirely behind Virginia when it seceded, and he volunteered in the Confederate army in a non-fighting capacity. He served for a time as a chaplain, and was later appointed chief of staff for the famed General Stonewall Jackson (whose biography he would write on commission from Jackson’s widow). Following the defeat of the South, Dabney was appalled and grieved by the demise of the civilization of old Virginia and by the harsh measures of reform imposed by the North. He briefly contemplated emigrating, but decided to remain and continue his work as professor and pastor. However, seeing the defeat of his native state was to leave a permanent mark on Dabney that would eat away at him throughout his remaining years.

In 1883, Dabney, now in his sixties, accepted an appointment as professor of moral and mental philosophy at the newly organized University of Texas. The principal reason for his leaving Virginia seems to have been the advice of doctors to seek a warmer climate to support his wavering health. Despite advancing years and the onset of blindness, Dabney took up his new task with vigor. In addition to teaching philosophy, he instructed students in economics, became involved with ecclesiastical affairs in Texas, and was instrumental in founding the Austin Theological Seminary, a school designed to provide badlyneeded pastors for the Texas Presbyterian churches. His teaching career came to an end before Dabney would have wished. In 1894 the University decided to relieve the blind 74-year-old of his duties, but he continued to write almost to the day of his death, January 3, 1898.

DABNEY’S THEOLOGY

Giving an assessment of Dabney’s life and work in a short paper like this is difficult and necessarily superficial. Dabney was a complex man of many interests who did not hesitate to stand up for unpopular and controversial causes. As a man of the church, Dabney was a staunch old-school Presbyterian who was a leading force in the foundation of the Southern Presbyterian Church at the time of the Civil War—and a leading opponent of merging back with northern Presbyterians after the war. Any new movement in the church that could be considered the least bit liberal was sure to find staunch resistance from Dabney, and he was perhaps the most revered leader among the most conservative of the Southern Presbyterians. He defended traditional Calvinist ideas like strict Sabbath observance, no instrumental music in worship, and presbyterian church government (or at least his own somewhat controversial version of it). On broader theological matters, Dabney also wrote extensively defending Reformed doctrines such as the substitutionary atonement and the bondage of the human will to sin. Readers of his theology should not expect to find too much that is original in terms of doctrines expounded, though he did write with a particular logical clarity and force of argumentation that sets forth many important doctrines in effective ways.

DABNEY’S IDEAS

But Dabney was more than just a churchman and theologian, and it may be his peculiar ideas on philosophical, social, educational and political issues which give Dabney his distinctive place in the pantheon of Reformed thinkers. The broad range of his thought is evidenced by his appointment to teach philosophy and economics at a late stage in his career after dedicating himself so long to theology, though in fact his writings throughout the course of his life display a keen interest in matters other than those which were strictly theological. An investigation of his ideas on some of these other issues, however, brings to light a Robert L. Dabney which is nothing short of scandalous at times. Standing out particularly are his militant defense of Southern slavery and his continuing advocacy of the subordination of blacks to whites even after the northern armies laid the slave system to rest.

Dabney believed that in this fallen world a system of slavery was at least an acceptable social arrangement, and in some circumstances he believed it was the best arrangement possible. He felt that economic and political liberty were privileges designed only for the virtuous and responsible members of society, and that if the uneducated, immoral and irresponsible people were granted these privileges, the resulting chaos and injustice would leave society without order or freedom. He defended his position with extensive Biblical arguments in which he tried to demonstrate that slavery, far from ever being condemned by God, was regulated by Him through detailed commandments to both masters and slaves. In his own setting, Dabney was convinced that the Africans brought to America as uncivilized, uneducated and non-Christian people, were just the sort of people unfit to be given much liberty. Though Dabney was insistent that masters treat their slaves fairly and provide for their material and spiritual needs, and though he severely condemned the failings of slaveholders in these areas, he believed that the system of slavery itself was acceptable to God and most conducive to producing peace and order in a community in which so many people, he thought, were incapable of living on their own. As a young man, Dabney hoped that the civilization of blacks would continue to progress and enable slavery to be ended peacefully in a short period of time. But with the onset of the Civil War and the sudden and violent emancipation that this conflict brought, Dabney despairingly thought that blacks had been given their freedom too soon and believed that their future prospects morally, religiously and economically, were dim. He repeatedly asserted that black people should not be given the right to vote and was a leading voice in the fight to keep blacks from being ordained in the Southern Presbyterian church.

EVALUATION

To find fault with Dabney on these issues is not difficult. Some of his writings contain inexcusably racist statements. And whatever one’s views on the pace of change and prospects for the peaceful end of slavery in the South, most can surely agree that once the Civil War and Reconstruction were fait accompli, Dabney’s bitter attitude and his refusal to consider the possibility of blacks’ contribution to society was not a model Christian approach. At the same time, one of the frustrating, and sometimes fascinating, things about Dabney is that amid the occasional comments that make us cringe, are extremely insightful and illuminating comments about society that Reformed Christians today would find very appealing. He warned of the corruptions which radical democratic and egalitarian impulses would bring into the political system-and looking at the state of modern American politics it is difficult to deny the force of his arguments. He also fought against the extension of public education in Virginia, and his arguments regarding the unavoidable deceptiveness of religiously-neutral education and the necessity of a distinctively Christian education would ring true for many of us today.

There is much profit in remembering men like Robert L. Dabney. His confident defense of the Reformed faith ought to serve as an inspiration to us in a day when it remains severely challenged. And his extensive commentary on the social issues of his day sheds interesting light on many of our own, often similar cultural struggles. Even his faults may serve as a warning to us of the dangers of unwarranted cultural assumptions pervading the life of even the most godly of people. One hundred years after his death, Robert L. Dabney remains one of the most interesting and controversial figures in the history of Reformed Christianity, and one still worth studying.

David M. VanDrunen is a graduate student atNorthwestern University School of Law and Trinity Evangelical Divinity Schoo!, and a member of Grace Orthodox Presbyterian Church in Hanover Park, Illinois.