This is the first half of an article reprinted from the July-August 1968 issue of The Outlook (then known as the Torch and Trumpet) in commemoration of the sixtieth anniversary of the founding of Reformed Fellowship, Inc. in April, 1951. The second half will appear, Lord willing, in the May-June issue.

EVERYWHERE in today’s world the Christian church is facing, with a new sense of urgency, the question of its calling. It confesses to having received the gospel of God’s grace in Christ Jesus. This, so the church acknowledges, must be presented and passed on. Such communication is its calling.

Communication by the church, however, is replete with frustrations. Nowhere do these come into sharper focus than when we become painfully aware of the multitudes estranged from the life of the church and its saving message. Bridges of all kinds are attempted between men and men, between one nation and another, between the church and the world. Frequently, however, the first piers sunk into the swirling waters are swept away. This happens most poignantly and painfully when the church sees children and young people, embraced by Christ’s baptism, turn away. Millions of these sustain no living relationship to the Word of life. To us who know and love the God of our salvation they seem like salt that has lost its savor. While on many mission fields and in younger lands the Christian church still appears to be registering advances, in the Western nations it beats a slow but sure retreat.

This points up what may well be the major issue facing the church today. Can it so communicate the Christian message that from one generation to the next God is praised among the peoples? Unless this can be done consciously and committedly, men will experience no true reconciliation. Hendrik Kraemer points this up well, when he writes,

Only the re-creation, the restoring, of the right relationship with God can be the basis of the re-creation of true unfrustrated communication with each other. This is one of the deep meanings of the Church, to be the place and sphere of this re-creation of true communication, because its function is to be the true community, founded through Christ in God, the embodiment of renewed humanity.1

Here the self-revealing God manifests himself, challenging the church to speak his word, which declares, “Light shall shine out of darkness, who shined in our hearts, to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6). Only such convinced speaking can communicate, for the Spirit honors the word that testifies faithfully to the grace of God in Christ Jesus. And those to whom the church is called to speak first of all are within her closest reach—the children whom he has embraced in his covenant and church. Their hearts and mouths must be opened by grace unto grace, so that also the next generation may know the mighty works of the Lord. To neglect them while seeking to communicate with others afar off is disobedience that flirts with spiritual disaster.

Time and again the church has had to be called back to this task. That Scripture is filled with exhortations to train the children of the covenant in the Lord’s fear needs no demonstration. Even the words of our Lord and his apostles on this point are too well-known to require repetition.

In the ancient church, however, this task was largely the responsibility of Christian parents. Such fathers as John Chrysostom, Rufinus, and Augustine, while speaking much of catechizing, only indirectly and by implication speak of the duty of the church to its own children. During the middle ages more attention was given to the baptized children. Yet here the church, while attempting to introduce the children and bind them to its life, largely failed to awaken a response of childlike faith in God and his promises. Scripture was too much obscured by an emphasis on living in submission to church ordinances. The voice of the saving Christ seemed strangely silent among the clamorings for an obedience that produced work-righteousness. The way of salvation was largely hidden from the sons of men. Failing to communicate the gospel to millions whom it had baptized, the medieval church demonstrated its desperate need for reform.

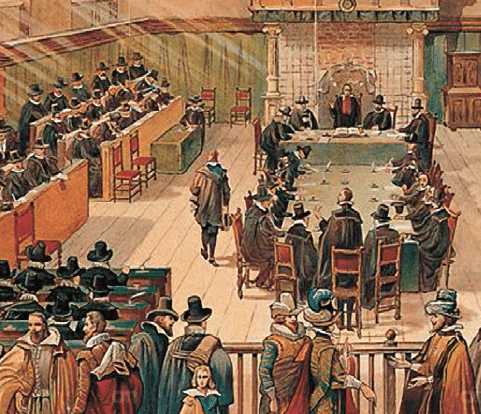

When the Reformation broke like bright dawn across Europe, all evangelical churches undertook with zeal the catechizing of the children of the church. This was an inescapable consequence of the restoration of preaching as the central act in the church’s worship and work. For unless the gospel message was clearly taught to the children, how could they in turn transmit this to their children? At stake was the continuity of a confessing church that knew what it confessed and aimed at passing this on to succeeding generations. Luther,2 Zwingli and Calvin,3 together with their followers, urged such Christian nurture as an integral aspect of the church’s calling. To secure this they prepared their catechetical manuals. Wherever these were used diligently, the life of the congregations grew in purity and strength. At the end of the first century of Reformation history appears the Synod of Dort (1618–19), an assembly of representatives from nearly every Reformed church on the continent. Here the fruits of a hundred years of trial and triumph were garnered, also those that had ripened as a result of the church’s deep concern for its baptized children and young people. And these were intended to be passed on, so that churches in the coming years might reap an even richer harvest. What Dort did for catechesis deserves some attention from us in these years when the churches throughout the world are again addressing themselves seriously to the problems surrounding church education of children.4

Catechesis in the churches

Catechesis is an aspect of the teaching ministry of the church. In the Reformed church it has historically been regarded as the chief means of communicating the Christian gospel to those whose spiritual life (i.e., life in faith-union and communion with God in Christ) has not attained that degree of maturity essential to a clear and credible profession of faith in the Lord Jesus Christ.

Here some distinctions deserve our attention. Not all education and training in the Christian life should be subsumed under catechesis. Also the faithful proclamation of the gospel at the time of public worship has an educational dimension. Here the church does well to remember that “Every Scripture inspired of God [and this alone is to be expounded and applied in the churches] is also profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, for instruction which is in righteousness” (2 Tim. 3:16).

Even pastoral work, when scripturally carried on, sustains an inescapable connection with the teaching function of the church.5 Yet catechesis performs a unique service. Here the church in Christ’s name instructs the catechumens in the mysteries of the Christian faith, so that they will be prepared to profess their faith in the God of salvation and thus be able to conduct themselves responsibly as Christian believers in the church and in the world. Today we recognize much more clearly than some centuries ago that the church has a catechesal responsibility not only to those who have received Christian baptism; without a “missionary” or “evangelistic” catechesis, which in several respects ought to be distinguished from catechesis within the churches, we fail to honor fully our Christ-given mandate.6

But, and this needs underscoring in our time, the church is by no means the only agency called upon to provide Christian education. Thus a distinction must be made between the responsibilities resting on the church and those that devolve on Christian homes and schools. While we may rejoice that today, under the influence of the ecumenical movement and its theologians the church, also in its institutional form, receives its due more justly than before, the danger of a totalitarian church is by no means imaginary. Here in more ways than one the views of the ecumenically-minded theologians at times sound strangely like Rome. By not a few, all religious and Christian education is assigned to the institutional church, a convenient escape from the impasse created by the increasing “secularization” of our homes and schools, but one fraught with great peril for the freedom of the Christian man, woman, and child under Christ.

Especially in Reformed churches during the past century this matter has received attention. Much more clearly than the fathers of Dort do we recognize that home and school and church each have unique contributions to make in the Christian education of children. But more, much more, needs to be clarified on this score, if the gains that have already been registered shall be sustained and strengthened. Catechesis is only one yet a most essential and indispensable agency for the education of children in the faith that is according to godliness.

This is still widely recognized in the Christian Reformed Church. Each year tens of thousands receive such instruction.7 It is not merely expected by the people; it is an obligation assumed by the churches in adopting as Church Order regulations also the following:

Article 63. Each church shall instruct its youth—and others who are interested—in the teaching of the Scriptures as formulated in the creeds of the church, in order to prepare them to profess their faith publicly and to assume their Christian responsibilities in the church and in the world.

Article 64. a. Catechetical instruction shall be supervised by the consistory. b. The instruction shall be given by the minister of the Word with the help, if necessary, of the elders and others appointed by the consistory. c. The Heidelberg Catechism and its Compendium shall be the basis of instruction. Selection of additional instructional helps shall be made by the minister in consultation with the consistory.8

Although somewhat more detailed, these regulations do not differ markedly from those adopted in earlier church orders, including the redaction prepared by the Synod of Dort. In this respect our churches—and not those that have substituted the usual Sunday school classes or discussion groups or junior church services—stand in the classic Christian tradition that goes back to Calvin and even earlier.

Such regulations alone, however, offer no assurance that the aims of catechesis will be attained. Above all else sound understanding of and whole-hearted commitment to this teaching ministry is necessary. And this seems sadly lacking among many.

Criticisms of the catechesal program are many. Some consistories pay no more attention to this work than making a few formal arrangements. Ministers are known to assign this task to others without serious qualms of conscience, in order to pursue what they deem more worthy of their time and attention. Not infrequently the catechesal classes are reduced to little more than half an hour and the catechesal season to not much more than twenty or twenty-five weeks in a year. In some churches these classes have become a rather meaningless routine conducted in drab and even dingy surroundings, which soon stifles any interest that the children may have. In others, experimentation with manuals and methods of all kinds tends to undermine the aims that the churches themselves have spelled out. That catechesis still yields some rich and rewarding fruits is often more in spite than because of us.

For much of this decadence, Christian parents as members of the church must bear a large measure of responsibility. The pressures that they bring to bear on this pattern of the church’s ministry, although often subtle, are exceedingly strong. Having enrolled their children, they will tend to do little more. A careful inquiry into and explanation of the lesson to the children at home takes too much of their time. Soon they allow dental appointments, basketball games, and family affairs to preempt the hour scheduled for catechesis. Not a few argue that these classes are quite unnecessary, since the material is identical to that presented in Sunday school and in the Christian day school. Others complain too quickly that the minds of the little children are being too much overburdened—and that in a day when thorough education in all other departments of learning is regarded as indispensable! All this demonstrates a declining interest in God and his service that plagues churches and church members in today’s “scientific” and so-called “secularized” world. Unless this and much else is remedied, the catechesal classes will go by default to the detriment of multitudes for generations to come. No church can be true church unless its members know and believe and testify to the gospel of our God. This calls for “indoctrination”—plain and patient and persistent teaching of the Christian faith that is unto godliness. Unless this is achieved, the church within a generation may no longer have a gospel to communicate.

But why speak about Dort in this connection? This question cannot be shoved under the rug. Too many people manifest a strong anti-historical bias. To them all that counts is what has been proposed no earlier than yesterday. The past is regarded as an accumulation of dead bones, of baggage that only hampers us in the adventure of living life to the full in these years.

To respond to them and their opinions fully would take too much space here. However, a few salient facts should be brought to their attention.

No generation among the sons of men lives without its strong and inescapable ties with the past. This is true also of Christ’s church. We cannot understand who we are and why we live as we do except we reflect on the life and labors of those who have gone before. The eminent Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, in an altogether different connection, calls attention to this in his Encounters in History.

History does not only fashion that understanding and participating attitude of mind in the most general way with respect to life and humanity; it calls forth feelings of kinship with the group to which the spectator belongs; it strengthens the sense of community. With understanding grows love for what one is a part of, and a more profound and firmer love as it is free from illusions. . . . It is not an escape from the present; it is strengthening ourselves for the struggle that is calling us.9

Nowhere is such strengthening more needful than in Christ’s church. Here by profession we acknowledge our kinship with all those called to salvation in Christ—“I believe one holy, catholic church.” This church, which lives in Christ and through Christ and for Christ, has been assured by him of the Spirit’s leading into all truth. This process, which spans the centuries, is his gift to us. And we disregard or disdain it to our grave spiritual impoverishment.

Gispen, that capable, justly famous and quite eccentric Reformed preacher of nearly a century ago, saw a striking parallel between the church and the circus. Acrobats make their appeal to the populace as some stand on the shoulders of others to reach even greater heights; they can soar safely through space from one trapeze to another only when in passing they seize and are propelled by others at the crucial moment. Here no individual can do without his partners. Communicating the gospel is a kind of spiritual acrobatics. We stand on the shoulders of the past; we are gripped by the trained hands of those who have gone before in order to move into the future with the full and rich Christian gospel that every age needs. And since our understanding of that message has to a large degree been shaped by Dort, we do only disservice to our self-understanding by disregarding it.

The roots of Reformed catechesis

If we cannot understand the catechesal pattern and practice of our churches apart from knowing something about Dort, we shall not be able to understand what and why Dort spoke on this without some consideration of what preceded the assembling of that synod. Its deliberations and decisions were not the product of a single day.

To only a few of the salient features of Reformed catechetical history can we call attention now.

Here the work of Luther and Calvin should be signalized.10 As reformers within Christ’s church their place is unparalleled. They called men throughout all of Christendom back to the Scriptures. Only on the basis of God’s word could the church be truly reformed. And in the task of reformation according to the Word the catechizing of children and young people was crucial. Both of them early in their reformational work prepared catechetical manuals for the children, so that the pure doctrine that is proper food and drink for the believing church might not perish but be perpetuated from generation to generation. And that the churches learned well from them is evident from the fact that during succeeding centuries confessional Lutheran and Reformed churches pursued the pattern that they learned from their “spiritual fathers in Christ.”

The teachings of Calvin spread by various means to the Netherlands of the sixteenth century. Here the churches early adopted a confession of faith that even in its details harmonized with what was taught in Geneva.

In order to promote the unity and strength of the Calvinistic reformation in the Netherlands, leaders met in the German town of Wesel and drew up a tentative Church Order. These articles did not possess official and binding status, since the Convent of Wesel (1568) was not a legally constituted assembly of representatives of the churches. Yet they provided the basis for church orders adopted by succeeding synods, beginning with Emden (1571).11

Wesel devoted an entire chapter to the teaching ministry of the churches, specifically that of catechizing. It affirmed that responsibility for this rested upon the ministry of the Word. Likewise, such catechizing “according to our judgment is positively (stellig) to be maintained in all churches.” It urged the Dutch-speaking churches to employ the Heidelberg Catechism and the French-speaking (Walloon) churches the Catechism of Geneva.12

Fully as significant were the deep pastoral concerns of this assembly. Every effort was to be put forth by the catechetes that the children, in accordance with their age, “not only learn to recite the Catechism accurately but also understand its content and retain this not only in their minds but also in the depths of their heart.” Thus careful and clear exposition was required of those who taught. The “simplest manner of speaking, which is appropriate to the understanding of children” was urged. And that such instruction might be consistently provided, parents were under obligation to present their children for such teaching “in the true religion and piety.” Those who refused to cooperate became subject to ecclesiastical censure.

This was the pattern soon confirmed and maintained officially by the Dutch churches.13 The close relation between the churches and the schools and between these churches and schools and the civil magistrates, occasioned by the recognition of the Reformed faith as the religion of the nation, gave rise to many knotty problems. This was especially true in those areas where the population had conflicting ecclesiastical loyalties. The schools were placed under supervision of the churches, specifically of the ministers. Also here the catechism was to be taught, at least two times each week. In addition, the schoolmasters were to see to it that the older children (usually boys) were brought to divine worship. The disadvantages of these regulations, especially to Roman Catholics, and to a lesser extent to Lutherans and Anabaptists, are obvious. Some classes and particular synods insisted on a rigorous enforcement; others with greater insight and wisdom modified their application. Thus the Gelderland synod held in Zutphen (1596) refused to compel children of Roman Catholic parents to attend Reformed worship even though they were to be instructed in the Heidelberg Catechism in the schools.14 The same synod, meeting in Nijmegen (1606), saw the issues involved even more clearly. In response to a gravamen presented by Harderwyk that was rejected, it declared that catechetical instruction was “an ecclesiastical matter” and that therefore “every church and minister shall labor to the end, that the members continue to send their children to catechism.”15

What especially constrained the Synod of Dort (1618–19) to address itself to catechesis was the Arminian controversy. This party—which sprang up in the Dutch churches and grew in influence for some twenty years—chafed at the rigid confessional and church-political requirements of the Reformed churches. By various and even devious means they sought to undermine the standards that had been adopted officially by the synods and to which they themselves had subscribed when assuming office in the churches. Time and again, at first very cautiously but afterward with growing boldness, they urged a revision of the Belgic Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism. Sometimes it was made to appear that they aimed at only minor redactional changes. But whenever they were requested to state clearly what they sought to have changed, an answer was not forthcoming. Rightly did those who championed the Reformed teachings fear that Arminian dissatisfaction and dissent was more deep-seated than its representatives were ready to admit. Tendencies in the direction of Semi-Pelagianism, Pelagianism, and even Socinianism betrayed themselves in the writings of several. Throughout this discussion the Arminians posed as champions of “moderation,” which to all practical purposes would mean a church no longer consistently bound by its own confessional statements. Catechesis as well as preaching in the pulpits was being affected. Many in the churches were confused as to what was a sound presentation of the Reformed faith. So sharply were the lines between the two parties drawn during the eight years before the Synod of Dort convened, that many congregations were rent by schism.

None of the Arminians, so far as we have been able to trace, ever argued against catechesis as such. What they aimed at, however, was quite different from the pattern pursued in the Reformed churches since their organization in the land. This becomes especially evident when we take note of the Gouda Catechism, which was drawn up by some of their leaders in 1607 and published the next year.16 The argument was that the Heidelberg Catechism was much too long and complicated to serve as a suitable manual for instruction. By no means could all of its contents be considered essential to a sound knowledge of the Christian faith. In fact, it was to be regarded as merely the work of men. Therefore a catechism was needed that adhered much more closely to the very words of Scripture, and then only those words (relatively few when we review this product of their pen) that were indispensable to a man’s salvation. We meet here, therefore, a kind of “Biblicism” that in Anabaptist fashion had no eye for the leading of the Holy Spirit throughout the centuries of church history as well as a kind of “reductionism” that is always characteristic of those who defend latitudinarianism in Christian doctrine.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the Synod of Dort felt constrained to speak on catechesal matters. Without using the word, it addressed itself to the communication of the gospel. And since this was to be done in classroom as well as from the pulpit, in order that the confessional church might truly be a confessing church, it addressed itself seriously to this aspect of the teaching ministry. Only in this way, so it believed, could the rich gains enjoyed since the days of Reformation be preserved for and passed on to the church of the future.

1. Hendrik Kraemer: The Communication of the Christian Faith (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1956), p. 19

2. On Luther’s Small Catechism cf. Philip Schaff: Creeds of Christendom, 4th ed. (New York and London: Harper & Bros., 1919), vol. I, pp. 247–253, and vol. III, pp. 74–92.

3. Calvin wrote two catechisms. The first has been translated by Paul T. Fuhrmann: Instruction in Faith (1537) by John Calvin (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1959). The second is reproduced by Thomas F. Torrance: The School of Faith (London: James Clarke & Co., 1959), pp. 4–65. For Calvin on catechesis, cf. the author’s article “Calvin’s Contributions to Church Education” in Calvin Theological Journal (Nov., 1967), vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 162–201.

4. Attention should be addressed to the renewal of catechesis in the various branches of Christendom. Here the lead has been taken by the Roman Catholic Church both with respect to “missionary” catechesis and catechesis for children of the church. The new Dutch catechism, approved by the hierarchy of the Netherlands, has occasioned much discussion and debate. Its “existentialistic” approach has rendered it highly suspect among conservative Catholics, both in Rome and the United States. Under the impact of neo-orthodoxy a flood of literature on this work has appeared in German-speaking lands. Both Hervormde and Gereformeerde churches in the Netherlands have “werk-groepen” that have addressed themselves to the same subject for several years. A renewal of the church’s teaching ministry, both with respect to message and form, is much discussed in the United States, usually in connection with the Sunday- or church-school. For a delineation of the issues involved and the radical differences between the Germans and the Americans on this score, cf. Arnold H. De Graaff: The Educational Ministry of the Church: a perspective (Delft: Judels & Brinkman, 1966), pp. 3–24.

5. J. Firet: Het Agogisch Moment in het Pastoraal Optreden (Kampen: J. H. Kok, 1968), who insists that all pastoral work, including therefore “zielzorg” of all kinds and pastoral counseling, is “ . . . not the activity of men, but the act of God, who via the intermediary of official ministry comes to men in his word” (italics ours) p. 25. The various ways in which the Word functions are discussed in great detail and depth, in which understanding cannot be separated from teaching which is or has been given.

6. Several reasons may be given why early Reformed churches, also at Dort, gave so little attention to Christian missions and therefore to “missionary catechesis.” Yet to say that nothing was done is a serious misrepresentation. Cf. the author’s article “Christian Missions in the days of Dort” in TORCH AND TRUMPET (May–June, 1968), vol. XVIII, No. 5, pp. 26–32. The unique dimensions of such catechesis even now are receiving a totally inadequate treatment by Reformed churchmen.

7. The most recent statistics (Jan. 1968) list 56,608 catechumens enrolled in Christian Reformed churches. During 1967 some 5,815 or slightly more than 10% made public profession of their faith. A carefully controlled inquiry into catechesal enrollment, attendance, etc. would be necessary to determine with any degree of accuracy present-day trends in the churches.

8. An interpretation of these articles is given in Monsma and Van Dellen: The New Revised Church Order Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Publishing House, 1967), pp. 249–254. Reference is also made to synodical decisions of the Christian Reformed Church.

9. Pieter Geyl: Encounters in History (Cleveland: The World Publishing Co., 1961), pp. 273, 274.

10. Kendig Brubaker Cully: Basic Writings in Christian Education (Philadelphia: The Westminster Press, 1960) contains Luther’s “To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany that they establish and maintain Christian Schools,” pp. 135–144, and Calvin’s “To the faithful Ministers of Christ who preach the pure doctrine of the Gospel in East Friesland,” pp. 165–169.

11. For this and other early church orders of the Reformed churches in the Netherlands cf. P. Biesterveld and H. H. Kuyper: Kerkelijk Handboekje (Kampen: J. H. Bos, 1905). The pertinent articles drawn up by the Convent of Wesel are found on pp. 15, 16.

12. By this the churches meant Calvin’s second catechism, drawn up in French in 1541, published in Latin in 1545.

13. A more detailed study of catechesis in the Dutch churches would require reference to the influence of early Reformed catecheticians, Hyperius and Zepperus.

14. Reitsma and Van Veen: Acta van de Particuliere en Provinciate Synoden (Groningen: J. B. Wolters, 1892) vol IV, p. 56.

15. Ibid., p. 145.

16. The Gouda Catechism, reproduced by Bakhuyzen vanden Brink: De Nederlandsche Belijdenisgeschriften, demonstrates clearly the radical difference between Arminians and Reformed on what constituted proper material for catechesal classes. A separate article should be devoted to this, because the differences spring from contradictory convictions concerning the church’s calling to communicate the gospel to its own generation as well as of the value and validity of the church’s doctrinal formulations. To the argumentation for the Arminian position presented at synod by the Remonstrant delegation of Utrecht, the response was given that the method they proposed would be a means to extirpate all other forms of catechizing and that there had never been produced any creed or catechism as they proposed. Cf. H. Kaajan: De Pro-Acta der Dordtsche Synode in 1618 (Rotterdam: T. De Vries, 1914), pp. 199–200.

Dr. P. Y. De Jong (1915–2005) wrote frequently for The Outlook. He is well-remembered as a prolific writer, professor at two seminaries, and brilliant preacher of God’s Word.