This is the second half of a chapter in Sing a New Song, a new book that covers the topics of psalm singing in history, psalm singing in Scripture, and psalm singing and the twenty-first-century church. Among the contributors are W. Robert Godfrey (foreword), Joel R. Beeke, Terry Johnson, D. G. Hart, Derek Thomas, and John V. Fesko. It will be available fall 2010 from Reformation Heritage Books (www.heritagebooks.org).

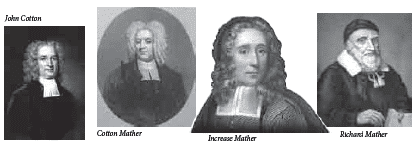

John Cotton (1584–1652), the well-known New England Puritan who may have written the preface to the Bay Psalm Book,1 wrote an important treatise in 1647, typical of Puritan thought: Singing of Psalmes: A Gospel-Ordinance Or A Treatise, Wherein are handled these foure Particulars. 1. Touching the Duty it selfe. 2. Touching the Matter to be Sung. 3. Touching the Singers. 4. Touching the Manner of Singing.2 This was “the first major work by a New Englander on psalmody and worship.”3 It is one of the best sources for the study of Puritan psalmody, as it carefully addresses the main issues in psalm singing. For most of the remainder of this chapter, we will follow Cotton’s four-step order.

The Duty of Singing Psalms

On the title page of the Bay Psalm Book, Cotton states that psalm singing is a gospel ordinance. His grandson Cotton Mather called psalm singing a “holy, delightful and profitable Ordinance in the Church or Household.”4 The Westminster Assembly divines said in their “Directory for the Publick Worship of God” that it is the duty of all Christians “to praise God publicly, by singing of psalms together in the congregation, and also privately in the family.”5

Cotton points out that Christ sang a psalm with His disciples after “the administration of the Lords Supper” (Matt. 26:30).6 Matthew Henry remarks: “Singing of psalms is a gospel-ordinance. Christ’s removing the hymn from the close of the passover to the close of the Lord’s Supper, plainly intimates that he intended that ordinance should continue in his church, that, as it had not its birth with the ceremonial law, so it should not die with it.”7

When Cotton Mather published Accomplish’d Singer in 1721, his father, Increase Mather, wrote an endorsement for the book, remarking that psalm singing was “somewhat lost in many places.”8 The problem was not new. Cotton had already dealt with it in Singing of Psalmes (1647). In the first section of this volume, Cotton specifically addresses the issue of vocal psalmody. He says there are “Antipsalmists, who doe not acknowledge any singing at all with the voyce in the New Testament, but onely spirituall songs of joy and comfort of the heart in the word of Christ.”9 In arguing for vocal psalms, Cotton cites two classic texts on singing psalms: Ephesians 5:19 and Colossians 3:16. He says that in these verses Paul exhorts us to sing not only silently in our hearts but also audibly with our voices.

Cotton further argues that lifted voices should be understandable, so that even uneducated hearers “might be edified, and say, Amen, at such giving of thankes” (1 Cor. 14:14–15).10 Psalm singing should bless not only the singer but also the listener. Yet, edification should not be the chief aim in singing—it should be God’s glory. As Cotton Mather declares, “Let a sincere View to the Honour of God (the great End of Psalmody) animate and regulate your Endeavors to attain this worthy Accomplishment. Let all be done after a godly Sort, that even by this common action you may please and glorify God.”11

Because God’s glory is psalmody’s supreme goal, the Puritans believed that singing in worship should be robust rather than reserved, as some have caricatured their singing. While the Puritans sang out of duty, they did so with profound joy and delight in their souls. That is why Mather calls psalm singing a “delightful ordinance.”

The Matter to Be Sung

Should singing in public worship be confined to the book of Psalms? Should congregations sing the songs of Moses, Mary, Elizabeth, and other biblical saints? And should the church be allowed to sing hymns composed by spiritually gifted believers? Cotton addresses these questions in the second part of his book.

Cotton says the singing of uninspired hymns should not be allowed in public worship.12 Quoting Ephesians 5:19 and Colossians 3:16, he says that when Paul exhorts or commands us to sing, he instructs us to sing “psalms and hymns and spiritual songs,” which, for Cotton, are “the very Titles of the Songs of David.”13 To stress his point, Cotton says that the word hymn in Matthew 26:30 is “the generall title for the whole Book of Psalmes.”14 Therefore, Paul was directing us to sing not hymns or spiritual songs written by any believer, but specifically the psalms of David. In Cotton’s mind, the title “Psalms or Songs of David” refers to all 150 psalms, even though David did not write all the psalms.

Other Puritans supported Cotton’s interpretation of Ephesians 5:19 and Colossians 3:16. In commenting on Colossians 3:16, Edward Leigh argues: “As the Apostle exhorteth us to singing, so he instructeth what the matter of our Song should be, viz. Psalmes, Hymnes, and spirituall Songs. Those three are the Titles of the Songs of David, as they are delivered to us by the Holy Ghost himself.”15 Similarly, Jonathan Clapham, maintaining the worth of singing David’s psalms, says, “The Apostle, Eph. 5 and Col. 3, where he commands singing of Psalmes, doth clearly point us to David’s Psalms, by using those, Psalmes, hymnes, and spirituall songs, which answer to the three Hebrew words, Shorim, Tehillim, Mizmorim, whereby David’s Psalmes were called.”16

Thomas Ford, a member of the Westminster Assembly of Divines, also affirmed this view. He asserted in his Singing of Psalmes: the duty of Christians under the New Testament. Or A vindication of that Gospel-ordinance in V. sermons upon Ephesians 5. 19. Wherein are asserted and cleared 1. That 2. What 3. How 4. Why [brace] we must sing (1653):

I know nothing more probable then this, viz. That Psalmes, and Hymns, and spiritual Songs, do answer to Mizmorim, Tehillim, and Shirim, which are the Hebrew names of David’s Psalmes. All the Psalmes together are called Tehillim, i.e. Praises, or songs of praise. Mizmor and Shir are in the Titles of many Psalmes, sometimes one, and sometimes the other, and sometimes both joyn’d together, as they know well who can read the Originall. Now the Apostle calling them by the same names by which the Greek Translation (which the New Testament so much follows) renders the Hebrew, is an argument that he means no other then David’s Psalms.17

Ford’s statement is important because it indicates that when the Westminster Confession of Faith says that “singing of psalms with grace in the heart” is a part of “the ordinary religious worship of God” (21.5), it means exclusively the book of Psalms.18

Nick Needham, however, suggests that the framers of the confession did not intend the word psalms to mean only the psalms of David.19 Needham argues:

If only they [the composers of the confession] had written ‘David’s psalms,’ that would be an end of the matter. But they did not write ‘David’s psalms.’ From a purely linguistic standpoint, it is therefore wholly possible and legitimate to interpret the unqualified word ‘psalms’ in 21.5 either as David’s psalms, or as religious songs in general.20

This would thus allow for uninspired hymns.

Matthew Winzer, who understands the term psalms in the confession to refer strictly to the book of Psalms, challenges Needham’s view. Winzer concludes that Needham “failed to properly represent the view of the Westminster Assembly when he claims that exclusive psalmody is the least probable historical-contextual interpretation of the reference to ‘singing of psalms’ in Confession 21.5.”21 Winzer’s argument seems to hold more weight than Needham’s.

Though Cotton made a strong case for the exclusive psalmody interpretation of Ephesians 5:19 and Colossians 3:16, he was not a strict advocate of exclusive psalmody. He stated: “Not onely the Psalms of David, but any other spirituall Songs recorded in Scripture, may lawfully be sung in Christian Churches, as the song of Moses, and Asaph, Heman and Ethan, Solomon and Hezekiah, Habacuck and Zachary, Hannah and Deborah, Mary and Elizabeth, and the like.”22

As for doctrinally sound uninspired, or extra-scriptural, hymns, Cotton says they should not be sung in public worship, but they may certainly be sung in “private houses.”23 He instructed,

We grant also, that any private Christian, who hath a gift to frame a spirituall Song, may both frame it, and sing it privately, for his own private comfort, and remembrance of some speciall benefit, or deliverance: nor doe we forbid the private use of an Instrument of Musick therewithal; So that attention to the instrument, doe not divert the heart from attention to the matter of the Song.24

Cotton does not deny “that in the publique thankesgivings of the Church, if the Lord should furnish any of the members of the Church with a spirituall gift to compose a Psalme upon any speciall occasion, he may lawfully be allowed to sing it before the Church, and the rest hearing it, and approving it, may goe along with him in Spirit, and say Amen to it.”25

In a word, Cotton sanctioned singing newly composed religious songs, but only in special gatherings. He was concerned that only David’s psalms and other Scripture songs be sung in worship services.26

The Singers

Who must sing these divinely inspired songs? Should an individual be allowed to sing for the congregation, or should the entire congregation sing? Should men and women sing, or men only? Should unbelievers be allowed to sing with believers? Should people who are not church members be allowed to sing? Cotton addresses these kinds of questions in the third section of his book.

While solos might be appropriate in other settings, Cotton says that in public worship God wants the entire congregation to sing together. Intriguingly, Cotton explains that after partaking of the Lord’s Supper, Jesus and His disciples—a sort of congregation—sang a psalm. Likewise, in the Old Testament, “Moses and the children of Israel [who were a body of people] sang a Song of Thanksgiving to the Lord” (Exod. 15:1).27

Cotton says women may sing along with men in congregational singing, citing Exodus 15:20–21, which says that Miriam and other women sang God’s praises along with men. For Cotton, this passage is sufficient ground “to justifie the lawfull practice of women in singing together with men.”28

Cotton spends much time addressing the questions of whether believers who are not members of the local church and unbelievers are allowed to sing with believing church members in public worship. Some people in Cotton’s day believed that only professing church members had the right to sing during a worship service. Cotton’s response was that since psalm singing is a moral duty of all Christians, every person, whether a church member or not, is “bound to sing to the praise of God.”29 He says psalm singing is a “generall Commandment”; thus, as the psalms themselves make clear, everyone in the world—including unbelievers—is called to lift up their voices to the Lord. Scripture is plain: “O sing unto the Lord a new song: sing unto the Lord, all the earth” (Ps. 96:1); “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all ye lands” (Ps. 100:1); “Sing unto God, ye kingdoms of the earth; O sing praises unto the Lord; Selah” (Ps. 68:32).30

Not all Puritans agreed with Cotton on granting unbelievers the right to participate in congregational singing. For example, this issue surfaced in John Bunyan’s Bedford meeting house. Two years after Bunyan’s death, the Bedford church met and “discussed the subject and gravely decided . . . that Publick Singing of Psalms be practiced by the Church with a caution that none others perform it but such as can sing with grace in their Hearts according to the command of Christ.”31

The Bedford congregation’s conviction was not uncommon among separatist churches, which said a local church should consist only of believers; thus, in public worship, only believers should sing. But Cotton made it clear that on the basis of the general nature of the command to sing to the Lord, none is “exempted from this service.”32 Most Puritans agreed. However, Cotton acknowledged that “the grounds and ends of Singing . . . peculiarly concerne the Church and people of God and therefore they [the believers] of all others are most bound to abound in this Dutie.”33 While the unsaved are commanded to make melody to the Lord, the redeemed should delight in this command.

The Manner of Singing

In the final segment of Singing of Psalmes, Cotton addresses the issue of whether it is lawful to sing psalms in meter to tunes invented by men. Using common sense, Cotton reasons that if it is “the holy will of God, that the Hebrew Scriptures should be translated into English Prose in order unto reading, then it is like sort his holy will, that the Hebrew Psalmes, (which are Poems and Verses) should be translated into English Poems and Verses in order to Singing.”34 Practically speaking, Cotton says a metrical psalter makes “the verses more easie for memory, and more fit for melody.”35 Hence, singing David’s psalms in meter is not only proper but also wise.

As for tunes, Cotton says that since the Lord “hath hid from us the Hebrew Tunes, and the musicall Accents wherewith the Psalmes of David were wont to be sung, it must needs be that the Lord alloweth us to sing them in any such grave, and solemne, and plaine Tunes, as doe fitly suite the gravitie of the matter, the solemnitie of Gods worship, and the capacitie of a plaine People.”36 God gives us freedom to compose reverent tunes for the Psalms, so long as the rhythm and tunes are pleasing to God and edifying to His people.37 We should never use this liberty to satisfy our selfish desires.

Cotton suggests that a minister read each line of a psalm before asking the congregation to sing it. Though the Bible does not require this practice, Cotton found it helpful “that the words of the Psalme be openly read before hand, line after line, or two lines together, that so they who want [lack] either books or skill to reade, may know what is to be sung, and joyne with the rest in the dutie of singing . . . and by Singing be stirred up to use holy Harmony, both with the Lord and his people.”38

The Westminster divines similarly advise:

In singing of psalms, the voice is to be tunably and gravely ordered; but the chief care must be to sing with understanding, and with grace in the heart, making melody unto the Lord.

That the whole congregation may join herein, every one that can read is to have a psalm book; and all others, not disabled by age or otherwise, are to be exhorted to learn to read. But for the present, where many in the congregation cannot read, it is convenient that the minister, or some other fit person appointed by him and the other ruling officers, do read the psalm, line by line, before the singing thereof.39

A “Puritan” Baptist Exception

As Puritanism waned at the close of the seventeenth century, a Puritan-minded Baptist preacher named Benjamin Keach (1640–1707) introduced hymns, in addition to psalms and paraphrases, into the English Nonconformist churches. He began by allowing one hymn after each administration of the Lord’s Supper, and then moved to one hymn per Sabbath.40 Eventually he became “a pioneer of congregational hymn singing.”41

In response to Isaac Marlow’s A Brief Discourse Concerning Singing in the Public Worship of God in the Gospel Church (1690), which argued that hymn singing was a distraction from the plainness of Puritan worship,42 Keach wrote his first book on the subject: The Breach Repaired in God’s Worship; or Singing of Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs, Proved to Be an Holy Ordinance of Jesus Christ (1691). Keach argued for hymn singing based on examples from David, Solomon, and others, and its “educational value.” This book, together with Keach’s Spiritual Melody; containing near Three Hundred Sacred Hymns (1691), created quite a stir, even in Keach’s own church, where nine people withdrew their membership. That, however, was the tip of the iceberg. Marlow responded with an appendix to his own book even before Keach’s The Breach Repaired was available to the public, moving Keach to add an appendix to his own book. That sparked pamphlet war among a number of pastors, most of whom supported Keach. Despite this, Keach lost an additional twenty members to Robert Steed, who wrote against the congregational hymn singing in An Epistle Written to the Members of a Church in London Concerning Singing (1691).43 The following year the issue of hymn singing reached the General Assembly, which censured both sides for their uncharitable reflections against their brethren; with that, the pamphlet war ceased for four years.44

In 1696, pamphlet war began again after Keach published A Feast of Fat Things; containing several Scripture Songs and Hymns. In all, Keach himself wrote nearly five hundred hymns and promoted hundreds more by publishing hymnbooks that circulated throughout the United Kingdom and North America. His work paved the way for Isaac Watts (1674–1748), often called “the father of English hymnody,” whose renowned Hymns and Spiritual Songs (1707) dealt a serious blow to the fading Puritan convictions about Psalm singing in public worship.45 For the first time in church history, man-made hymns replaced psalm singing.46

Conclusion: Practical Benefits of Psalm Singing

Albert Bailey rightly concludes that Calvin’s theological beliefs about the Psalter helped unite the Reformers and Puritans around the conviction that “only God’s own Word was worthy to be used in praising Him.”47 Psalm singing was important to Calvin and the Puritans, however, not only because it is biblical and historical and is our theological and moral duty to God, but also because of the gracious effects it has upon those who sing. Here are some spiritual and practical benefits of psalm singing:

Psalm singing comforts the soul. It lifts up the spiritually downcast and provides spiritual riches that are Christ-centered and experiential. Cotton says psalm singing “allayeth the passions of melancholy and choler, yea and scattereth the furious temptations of evill spirits, 1 Sam. 16.23.”48 It “helpeth to ass[u]age enmity, and to restore friendship favour, as in Saul to David.”49 Increase Mather observes “that musick is of great efficacy against melancholy.” Mather says, “the sweetness and delightfulness of musick has a natural power to [overcome] melancholy passions.”50

For Calvin and the Puritans, a psalter is what Robert Sanderson (1587–1662) called “the treasury of Christian comfort.”51 Sanderson, Bishop of Lincoln, ejected from his professorship at Oxford and imprisoned by Parliament, found great comfort through difficult times in the psalter. Subsequently, he wrote that a psalter is

fitted for all persons and all necessities; able to raise the soul from dejection by the frequent mention of God’s mercies to repentant sinners: to stir up holy desire; to increase joy; to moderate sorrow; to nourish hope, and teach us patience, by waiting God’s leisure; to beget a trust in the mercy, power, and providence of our Creator; and to cause a resignation of ourselves to his will: and then, and not till then, to believe ourselves happy.52

Psalm singing cultivates piety. Lewis Bayly included a section on psalm singing in The Practice of Pietie. He set down five rules for psalm singing:

1. Beware of singing divine Psalmes for an ordinary recreation; as do men of impure Spirits, who sing holy Psalmes, intermingled with prophane Ballads. They are Gods Word; take them not in thy mouth in vaine.

2. Remember to sing Davids Psalmes, with Davids Spirit.

3. Practice Saint Pauls rule: I will sing with the Spirit, but I will sing with the understanding also.

4. As you sing, uncover your heads, and behave your selves in comely reverence, as in the sight of God, singing to God, in Gods owne Words: but bee sure that the matter makes more melody in your hearts, then the Musicke in your Eares: for the singing with a grace in our hearts, in that which the Lord is delighted withal. . . .

5. Thou maist, if thou thinke good, sing all the Psalmes over in order: for all are most divine and comfortable. But if thou wilt chuse some speciall Psalmes, as more fit for some times, and purposes: and such, as by the oft-usage, thy people may the easilier commit to memory.53

Finally, psalm singing helps us glorify God, as the Reformation and post-Reformation divines tell us repeatedly. Wilhelmus à Brakel, a primary Dutch Further Reformation divine, writes: “Singing is a religious exercise by which, with the appropriate modulation of the voice, we worship, thank, and praise God.”54 Therefore, let those who sing, sing for the praise of God! “Sing praises to God, sing praises: sing praises unto our King, sing praises. For God is the King of all the earth: sing ye praises with understanding” (Ps. 47:6–7).

Taken from Sing a New Song, © 2010 by Joel R. Beeke and Anthony T. Selvaggio. Used by permission of Reformation Heritage Books, 2965 Leonard Street, NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49525. All rights reserved. 1. Ibid., 18. Perry Miller and Thomas Johnson, on the other hand, believe Richard Mather wrote the preface. See their The Puritans (New York: American Book, 1938), 669.

2. London: Printed by M. S. for Hannah Allen, at the Crowne in Popes-head-alley: and John Rothwell at the Sunne and fountaine in Pauls-church-yard, 1647. Hereafter, Singing of Psalmes.

3. David P. McKay, “Cotton Mather’s Unpublished Singing Sermon,” New England Quarterly 48, 3 (1975): 413.

4. “Text of Cotton Mather Singing Sermon April 18, 1721” in ibid., 419.

5. “The Directory for the Publick Worship of God,” in Westminster Confession of Faith (1646; Glasgow: Free Presbyterian Publications, 1997), 393.

6. Singing of Psalmes, 7.

7. Matthew Henry, Commentary (Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 1991), 5:318.

8. See “An Attestation from the Very Reverend Dr. Increase Mather,” in Cotton Mather, Accomplish’d Singer (Boston: Printed by B. Green, for S. Gerrish at his Shop in Cornhill, 1721).

9. Singing of Psalmes, 2.

10. Ibid.

11. “Text of Cotton Mather Singing Sermon April 18, 1721,” in McKay, “Cotton Mather’s Unpublished Singing Sermon,” 422.

12. Singing of Psalmes, 32.

13. Ibid., 16.

14. Ibid., 25.

15. Edward Leigh, Annotations upon all the New Testament philologicall and theologicall wherein the emphasis and elegancie of the Greeke is observed, some imperfections in our translation are discovered, divers Jewish rites and customes tending to illustrate the text are mentioned, many antilogies and seeming contradictions reconciled, severall darke and obscure places opened, sundry passages vindicated from the false glosses of papists and hereticks (London: Printed by W. W. and E. G. for William Lee, and are to be sold at his shop, 1650), 306.

16. Jonathan Clapham, A short and full vindication of that sweet and comfortable ordinance, of singing of Psalmes. Together with some profitable rules, to direct weak Christians how to sing to edification. And a briefe confutation of some of the most usual cavils made against the same. Published especially for the use of the Christians, in and about the town of Wramplingham in Norf. for the satisfaction of such, as scruple the said ordinance, for the establishment of such as do own it, against all seducers that come amongst them; and for the instruction of all in general, that they may better improve the same to their spiritual comfort and benefit (London: [s.n.], Printed, anno Dom. 1656), 3.

17. Thomas Ford, Singing of Psalmes: the duty of Christians under the New Testament. Or A vindication of that Gospel-ordinance in V. sermons upon Ephesians 5. 19. Wherein are asserted and cleared 1. That 2. What 3. How 4. Why [brace] we must sing (London: Printed by A. M. for Christopher Meredith at the Crane in Pauls Church-yard, 1653), 15, 16.

18. Westminster Confession of Faith, 92.

19. Nick Needham, “Westminster and Worship: Psalms, Hymns, and Musical Instruments?” in The Westminster Confession into the 21st Century, ed. J. Ligon Duncan (Fearn, Ross-shire: Mentor, 2003), 2:250–53.

20. Ibid., 253.

21. Matthew Winzer, “Westminster and Worship Examined: A Review of Nick Needham’s essay on the Westminster Confession of Faith’s teaching concerning the regulative principle, the singing of psalms, and the use of musical instruments in the public worship of God,” The Confessional Presbyterian 4 (2008): 264.

22. Singing of Psalmes, 15.

23. Ibid., 32.

24. Ibid., 15.

25. Ibid.

26. For Thomas Manton’s similar view, see William Young, The Puritan Principle of Worship (Vienna, Va.: Publications Committee of the Presbyterian Reformed Church, n.d.), 27–28.

27. Singing of Psalmes, 40.

28. Ibid., 43.

29. Ibid., 44.

30. Ibid., 45.

31. Scholes, The Puritans and Music in England and New England, 268.

32. Singing of Psalmes, 45.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid., 55.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid., 56.

37. Ibid., 60.

38. Ibid., 62–63. For more on Cotton’s view, see Young, The Puritan Principle of Worship, 20–27.

39. “The Directory for the Publick Worship of God,” in Westminster Confession of Faith, 393.

40. J. R. Watson, The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), 110; cf. Horton Davies, Worship and Theology in England from Andrewes to Baxter and Fox, 1603–1690 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), 510.

41. Hugh Martin, Benjamin Keach, Pioneer of Congregational Hymn Singing (London: Independent Press, 1961).

42. For Isaac Marlow, see Davies, Worship and Theology in England from Andrewes to Baxter and Fox, 274–75.

43. James Patrick Carnes, “The Famous Mr. Keach: Benjamin Keach and His Influence on Congregational Singing in Seventeenth Century England” (M.A. thesis, North Texas State University, 1984), 59–61.

44. Robert H. Young, “The History of Baptist Hymnody in England from 1612 to 1800” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, 1959), 43–44.

45. Carnes, “The Famous Mr. Keach,” 94–95. For a succinct study of Watts, see Watson, The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study, 133–70; cf. Darryl Hart’s chapter in this volume.

46. LeFebvre, To Sing the Psalms, Again, 14.

47. Albert Edward Bailey, The Gospel in Hymns: Backgrounds and Interpretations (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1950), 17.

48. Singing of Psalmes, 4.

49. Ibid., 4.

50. Increase Mather, A History of God’s Remarkable Providences in Colonial New England (1856; reprint, Portland, Ore.: Back Home Industries, 1997), 187.

51. Cited in Rowland E. Prothero, The Psalms in Human Life (1903; reprint, Birmingham. Ala.: Solid Ground Christian Books, 2002), 176.

52. Cited in ibid.

53. Lewis Bayly, The Practice of Pietie (London: Printed by R. Y. for Andrew Crooke, 1638), 233–34.

54. Wilhelmus à Brakel, The Christian’s Reasonable Service, trans. Bartel Elshout, ed. Joel R. Beeke (Morgan, Pa.: Soli Deo Gloria Publications, 1995), 4:31

Dr. Joel R. Beeke serves as President and Professor of Systematic Theology, Church History, and Homiletics at Puritan Reformed Theological Seminary. He is a prolific author and is also pastor of Heritage Reformed Church in Grand Rapids, MI.