The last of the days for commemoration listed in the Reformed Church Order is Pentecost. It is a day with which Reformed people sometimes seem to be ill at ease. Pentecost prompts articles on “The Holy Spirit: The Forgotten Person of the Trinity?” (a question sometimes answered positively and sometimes negatively) or “John Calvin: Theologian of the Holy Spirit.” In some places, depending on the year, the commemoration of Pentecost even has to share time with the high holy day of the greeting card industry: Mother’s Day.

Interestingly enough, in the early church, “Pentecost” designated the entire fifty day period following Easter. It was a period of great rejoicing during which neither fasting nor kneeling was allowed, and during which baptisms regularly took place.1

The period of Pentecost was seen as displaying the significance of Easter. Gradually, the fiftieth day of this period became the feast commemorating the giving of the Holy Spirit to the church by the ascended Christ. In the Reformed churches, with their more restrained view of days of commemoration, the 50 day period of Pentecost was replaced by the celebration of a single day.

The choice of the fiftieth day corresponded to the Old Testament feast called the Feast of Harvest (Ex. 23:16), or the Feast of Weeks (Deut. 16:9–12), or Pentecost (Acts 2:1). The feast took place 50 days after the day after the sabbath which fell during the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Lev. 23:15–21).

Why is it dated in this way? On the day after the sabbath during the Feast of Unleavened Bread, a sheaf of the first fruits was waved before the LORD (Lev. 23:9 ff.). That is, the priest would elevate it to the LORD. The idea was that the sheaf of the first fruits was given to the LORD and then received back from Him.

The first fruits were only acceptable when they were received back from the LORD. Along with the first fruits, an ascension offering was brought to show the total dedication of the worshipper to the LORD. With that offering also came a tribute offering that was twice the size of the normal tribute offering. The offering of grain on top of the ascension offering was a presentation of Israel’s work to the LORD. It acknowledged that the LORD was the real author of the land’s produce. Thus, a double portion of the previous year’s harvest was brought to Him. None of the early harvest could be eaten until the first fruits were given to the LORD. He is the owner of the land. For Israel to eat first would be a shocking lack of gratitude.

Pentecost built off of this waving of the first fruit. It came seven weeks later reminding Israel of what the LORD had done. Israel was to live out of the LORD’s provisions. The feasts showed that the LORD was Israel’s King and that by His blessing, she was His new creation.

This new creation aspect is highlighted when we consider the connection between the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Passover) and Pentecost. Passover commemorated God’s deliverance.

With Passover, the old leaven was cut off and Israel received new life from God. This new life grew for seven weeks. Then, at Pentecost, the leavened loaves were brought to the Tabernacle. God had given new growth and new life. The Pentecost Feast celebrated the gracious founding and consummation of the covenant.

Leaven could not be placed on the altar (Lev. 2:11) because Israel was not to give new life to God, they could only receive it from him. Symbolically, Israel had seven weeks of righteous growth and then they presented to the LORD what He first gave to them.

The old leaven of sin and death had been purged. The new life had grown to be a tribute offering of two leavened loaves. This was the double portion, the portion of the firstborn. God grew His kingdom from the sacrifice of the lamb (representing the firstborn son), to the waving of the first sheaf of new grain, to the waving of two leavened loaves after a sabbath of weeks. We could, without much difficulty, relate this to the Year of Jubilee which celebrated the LORD’s release of captives and His provision of life for His people (Lev. 25:8–17).

This is closely linked to Israel’s life as the people of God. The loaves were for the priests. In Leviticus 23:22 we find a repetition of the law about gleaning (Lev. 19:9–10). As Israel gave the gifts of the harvest to the LORD, they also had to express compassion toward the poor. The care for the priests and for the poor illustrated how Israel must live as the communion of the LORD’s holy ones.

We must, however, go one step further. Pentecost was closely linked with the harvest and, therefore, with the LORD’s mighty act of bringing Israel into the land. Pentecost also commemorated the giving of the Law at Sinai.2 Sinai was the goal of the exodus (Ex. 3:12). At Sinai, the LORD dwelt in the midst of Israel, spoke to them, and renewed the covenant. Pentecost, then, celebrated the gracious founding and consummation of the covenant. It celebrated the LORD taking Israel as His Bride. Indeed, the language of Exodus 19:4 is marriage-type language. At Sinai, Israel was recreated and renewed as the LORD provisionally dwelt in their midst.3

With this background, it is not difficult to see the fulfillment of these themes in Jesus Christ. The great act of deliverance in the Old Testament was the exodus from Egypt which was memorialized in the Passover and fulfilled on Pentecost. The great act of deliverance in the New Testament is the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, our Passover (I Cor. 5:7), and is fulfilled in Pentecost. In His death, the old leaven was definitively, once-for-all cut off. He was raised on the day after the sabbath during the Feast of Unleavened bread. That is, He was raised as the First Fruits, offered to God, and received back from Him. This marks the beginning of new life.

Jesus was raised on the first day of the week. If we look at it in terms of His completing Adam’s defiled week, He was raised on the eighth day, the day of new creation.4 Fifty days later there is the recreation of God’s people with the full and final outpouring of the Holy Spirit. In both the Old and the New Covenants, Pentecost is the Feast of the Word and the Spirit.

Here we need to remember that Old Testament history is, essentially, the history of exile from the LORD. Adam and Eve are expelled from the Garden-Sanctuary of God. From that time until the building of the Tabernacle, there was no central sanctuary on earth. Even with the Tabernacle, and later the Temple, there are all sorts of degrees of access, of who could draw near and how close one could come. The High Priest was permitted to enter the Most Holy Place, but only once a year on the Day of Atonement, and then only for a brief time. The priests could enter the Holy Place. They were allowed to eat the showbread, and were given portions of certain sacrifices, but they only served in the sanctuary and had to leave the Holy Place when their work was done. The Levites were allowed to serve in the Tabernacle courtyard as guards and servants, but they could not enter the sanctuary. Israelites, who conformed to the laws of cleanness, could come up to the altar in the courtyard of the Tabernacle and offer sacrifices, but they could not go any further.

Unclean Israelites were not allowed enter the Tabernacle at all, nor could they bring sacrifices until they had been cleansed. Beyond this were the unbelieving nations who had no access at all. The people were basically exiled from God. The whole Old Testament says, “Come close, but not too close.”

Of course, the Holy Spirit was active among God’s people. And, of course, people were saved the same way under the Old Covenant that they are under the New Covenant: by grace through faith – in the Old Covenant, faith in the promise of God of the coming Seed of the Woman. There are not different ways of salvation in the Old and New Covenants. That being said, however, the outpouring of the Spirit was limited in the Old Covenant. Yes, individual Israelites could pray, but they prayed on the basis of the work of the priests in the central sanctuary. They drew near through the priesthood and the sacrificial system. In the Old Covenant, God’s people were “slaves,” in the sense that they did not know what their Master was doing; in the New Covenant, we are called “friends” for we have greater access (John 15:14, 15).

(Because of the sentimentality surrounding this verse in the minds of many, we ought to be clear what “friend’ means in this context. “Friend,” here, is an official position. Pilate, for example, was called “Friend of Caesar.” This did not mean that he and Tiberius shared a bond of friendship. It meant that he was part of Caesar’s court, that he could advise Caesar and would be heard by him, that Caesar would consult him in matters pertaining to Judea – in short that he had access. The disciples, and the church built on them, are “Friends of Christ” in this sense. This explains why, while Jesus calls the disciples “friends,” they are not given leave to call Him “friend.”)

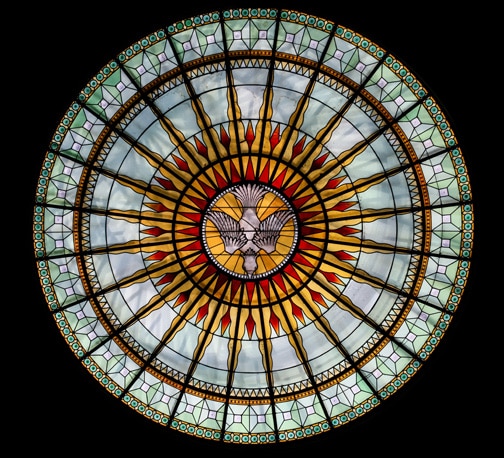

Christ recreated and renewed His people, and He now dwells with us. This is what Pentecost speaks of and commemorates. With the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, the church is united to Christ and is seated in the heavenly places. All this explains the Sinai imagery in Acts 2. They are gathered in the upper room.5 As we saw last month, mountains, high places, rooftops, and upper rooms are meeting places of heaven and earth. The company of 120 “ascends” and we find Sinai-like phenomena. Sinai was covered with wind, fire, and thunder. Acts 2 has these same things and they fill the whole house just as the Glory-Cloud filled the Tabernacle and the Temple.

God lights the fire of the altar in both the Tabernacle and Temple. Here we find flames of fire on the heads of the members of the church. They are now the altar. Just as the fire on the altar represented the presence of God, here the tongues of fire represent God’s presence. And, mirabile dictu, they are not consumed, nor are they driven out for they are living sacrifices. When the Glory of God filled the Tabernacle and the Temple in the Old Testament, the priests could not enter in (Ex. 40:35; I Kgs. 8:10, 11). The whole book of Leviticus addresses this problem: how can an unholy people enter in before the holy God? In Acts 2, the church is marked out as the Temple of God, as His dwelling place.

On Pentecost, God’s Glory—His Spirit—comes on the church and consecrates her as the place where He is enthroned. And, immediately, they begin to proclaim God’s Word, the Gospel of Jesus Christ, just as God coming to Sinai led to His proclamation of His Torah to His people. By His Word and Spirit, Jesus Christ marks out a people as His true temple. The Holy Spirit is the coronation gift of Christ to His people. Through Christ and His Spirit, we have access to the Father (Eph. 2:18). The church enters the heavenly sanctuary. The church, especially as she is gathered for public worship on the Lord’s Day, is the heavenly sanctuary on earth. The Holy Spirit is the foretaste of all our gifts in Christ.

What is the great promise of the covenant? That God will be our God and we shall be His people. So what is promised in salvation? Union and communion with God and to partake of the divine nature (II Peter 1:4). In short, what is promised in salvation is God Himself. In the giving of the Holy Spirit, we receive God Himself as our Guarantee; at the consummation, we will receive more of what we already have – we will receive “more” of God Himself. All members of the church receive the Holy Spirit; they all share in the fullness of this union and communion, which begins with their baptism.

(While a detailed discussion of the speaking with “other tongues” would lead us far afield, we should note the following: this proclamation in tongues is in known languages and it is proclamation to Jews. If we compare this with I Corinthians 14:20 and Isaiah 28:11, we must conclude that ‘tongues” were a sign to the apostate people of Israel that the focus of God’s saving activity was moving from them to the nations. That is, the Jews were in the process of having their lampstand removed and would have to come out of national/ethnic Israel into the church to be considered God’s people. “Tongues” were a sign of judgment against the faithless people of Israel and, thus, ceased when the Canon closed and judgment was meted out to Israel in A.D. 70. Biblical tongues have nothing to do with modern “speaking in tongues.”)

The giving of the Holy Spirit is not an individual, ineffable, inner matter, but is for and in the context of the church—and by “church” here is not meant some phantasmagorical “invisible” church, but the visible gathering of God’s people under His office-bearers that is marked out by the preaching and hearing of His Word, the use of His sacraments, and the exercise of His discipline. This is the only church the Bible knows of. Sometimes we hear people talk about the “experience” of the Holy Spirit as a warm, gooey feeling. They sound, as Luther once said, as though they had “swallowed the Holy Spirit, feathers and all.” The Spirit is poured out for our living together as Church, as the communion of the saints. Just as the Old Testament Pentecost was marked out by care for the priests and the poor. The New Testament Pentecost is also marked by the communion of the saints.

The life of the Spirit is found in being baptized, confessing the truth, living obediently, worshipping, and taking the Lord’s Supper. There is nothing, at least nothing biblical, over and above this. The Holy Spirit works faith in us through the proclamation of the Word and strengthens us through the sacraments. The church is the product of the Holy Spirit. The local, visible church is where God’s Presence is. This is the seriousness of this – only this church, known clearly by the marks (Belgic Confession, art. 29), is the obligatory church, the place where we must be. The Holy Spirit works very publicly and corporately.

Augustine, in The Trinity, points out the trinitarian structure of Pentecost. With reference to Galatians 4:4–5, he notes that there is a sending of the Son by the Father for our salvation and a sending of the Spirit by the Father.6 The sending of the Son accomplished certain things in the history of God’s people; the sending of the Spirit also, then, accomplishes things. By the Lord and Giver of Life, we are united to Christ and share in His anointing. His work brings us, as God’s congregation, into the presence of the Father through the Son. We are filled with the Spirit, beginning, in our baptism, to serve God and one another. The gift of the Spirit is not to induce a private “Sweet Hour of Prayer” so that we can leave this “world of care.” The Spirit is poured out on us so that we would live peacefully and righteously, confessing the truth in Christ’s church.

Rev. Ken Kok

Endnotes

1 For the history of the celebration of Pentecost see Peter G. Cobb, “The History of the Church Year,” The Study Liturqy, edited by Cheslyn Jones. Geoffrey Wainwright, and Edward Yarnold (London: SPCK, 1978) pp.411, 412. Also see Robert Louis Wilken, “Is Pentecost a Peer of Easter? Scripture, Liturgy, and the ProDrium of the Holy Spirit,” Trinity, Time, and Church: A Response Theology of Robert Jenson, edited by Colin E. Gunton (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans, 2000), pp.159–160.

2Alfred Edersheim, The Temple: Its Ministry Services as They Were at the Time of Christ (Grand Rapids: William B.Eerdmans, 1983; reprint of 1874 edition), p. 261. Also see James B. Jordan, A Chronological and Calendrical Commentary on the Pentateuch (Niceville, FL: Biblical Horizons, 1995), pp. 48–49.

3 The Tabernacle may be seen as a portable Sinai, the LORD’s dwelling with His people. See Angel Manuel Rodriguez, “Sanctuary Theology in the Book of Exodus” Andrews University Seminary Studies, Summer 1986, vol 24, No. 2, pp. 127–145. See, especially, p. 133.

4 On the eighth day, see Alexander Schemann, Introduction to Liturgical Theology (Portland, ME: American Orthodox Press, 1966), translated by Ashleigh B. Moorhouse, pp. 61-63; Jean Danielou, The Bible and the Liturgy (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1956), pp. 262-286.

5 Without further detail, we may safely assume that the “one place” of Acts 2:1 is the upper room of 1:13. See James D.G. Dunn, The Acts of the Apostles (Valley Forge, PA: Trinity Press International, 1996), p. 24.

6Augustine, The Trinity (Brooklyn, City Press, 1991), translated by Edmund Hill, pp. 102f (Bk. 2.8–11).