Perhaps you have heard of a heart-warming story about a family so deeply in debt that it would never be able to pay its way out. Then out of nowhere a philanthropist comes along, pays the debt, and delivers them in a way that they could have never delivered themselves. There is a very popular show on TV in America right now called “Extreme Makeover: Home Edition.” The extreme makeover team gets applications from people all over the nation who are in extreme need. Usually the family has experienced some devastating disease, death, or tragedy that has cost them their home and their ability to rebuild it. With tears in everyone’s eyes, the extreme home makeover team moves into place, and within seven days, the team rebuilds the house, while the blessed family is off on some exotic vacation. The family returns to find that everything has not only been torn down and removed, but they return to a brand new, beautiful home. This is a great example of philanthropy.

Throughout the whole story of Ruth, the reader has witnessed Naomi’s family brought to utter destruction and hopelessness; the family’s needs are too costly for them to pay. What this family needs is a philanthropist! From the start of our story, we have pain, sorrow, and death. The death and destruction that grips our story leads to a break in the future hope of this family. Throughout the story we are longing for someone to do something. However, the redemption of the family is not easy. Our story marks Boaz out as a philanthropist.

What is a philanthropist and what is philanthropy? Philanthropy is a combination of two Greek terms; philos—love—and anthropos—man. Hence, at its root, philanthropy means the love of man. Philanthropy is defined as the voluntary promotion of human welfare at one’s own expense. The philanthropist usually has a deep desire to improve the material, social, and spiritual welfare of humanity, especially through charitable activities.

Another word, altruisism, is sometimes used to describe this kind of activity. Altruistic concern for human welfare and advancement is an outward, not an inward concern. To be altruistic is to be concerned for others. This is manifested by donations of money, property, or work to needy persons, by endowment of institutions of learning and hospitals, and by generosity to other socially useful purposes.

Even more pointedly, a philanthropist is someone who takes of his own resources and gives it to others without an expectation of return. The reason giving to museums, libraries, and hospitals is considered such a good example of philanthropy is related to the reality that these kinds of institutions don’t offer any kind of an immediate financial return on one’s investment. The investment is almost entirely for the good of someone else.

Athanasius was fond of using the word philanthropy. This word seemed to capture the essence of the incarnation of Jesus. Jesus was a lover of mankind. Perhaps the most characteristic element of Jesus’ love was that it was completely selfless. His love was a pouring out of himself on behalf of others. Even more astounding was the fact that this love was poured out toward sinners.

Our Savior is the source of all true philanthropy. Thus, when we find stories in the Bible that point us to Jesus, we find stories of philanthropy. Think about this as you see our story of Ruth and Boaz move towards its conclusion. Boaz is foreshadowing our Savior, and as such, he illustrates for us true philanthropy. He is the selfless husband, and Ruth is the blessed wife who humbly receives his love. She opens herself to Boaz as an empty widow, and he fills her. She lies at his feet, and he covers her. This is a beautiful picture of Jesus and the church.

Chapter 4 takes the reader to the conclusion of this story of philanthropy. The story has taken the final turn towards blessing. Yet, the reader may still be asking, what will happen next? For the closing scene, Samuel takes the reader to the city gate.

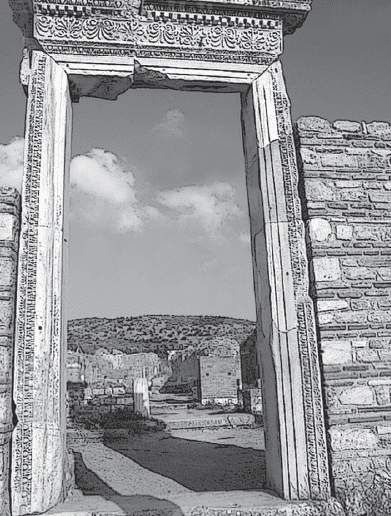

The Gate

This is like the city council or city courthouse; it is the place of life and death. The men sat down for business because the gates of a city were the place where legal transactions took place. It was the place of entrance for those who were admitted into the city. It was also here that you might be denied access. The gate is where you would be sentenced if you were convicted of a crime. People were stoned to death at the city gates. We see the same idea communicated in the New Testament when Jesus says that the gates of hell will not prevail against the church—the gate represents the authority of the city.

Mr. So-and-so

As they gathered at the gate, Boaz called out to a man who remained noticeably unnamed. He was conspicuously anonymous. In a story where the author uses names to teach theological lessons, the irony can sometimes be humorous. This is especially the case when the reader learns that this nameless relative was afraid of jeopardizing his name. Samuel uses a phrase that has baffled many scholars. Its origin and use is not known. It may have contained a word play, but we can’t be certain. Still, almost all agree that it was some kind of a colloquial phrase that could be translated as “so and so.” We could humorously call him Mr. “So-and-so.” He is deliberately nameless.

Here the nameless character is known to us only as a man who refused to act as redeemer in order to preserve his name. What an irony! The man said, essentially “I can’t do this because I will jeopardize my name, my inheritance!” He desperately wanted to do everything he could do to preserve his name, and in so doing, he lost the opportunity to have his name preserved.

It ought to strike us as highly ironic that the man so anxious to preserve his name and his inheritance is not known to us by name. If he would have responded to the duty of the Lord, we would now be speaking of him instead of Boaz. Is this not the paradox of which our Savior spoke in his own ministry? The man who seeks his life will lose it, but he who loses his life for Christ’s sake will gain it.

The relative in the story is called upon to serve his distant family member. As the story unfolds, Mr. So-and-so discovers that there won’t be any return on his investment in a financial sense. His return would have had to come in being satisfied with helping the relative—in being a servant to a needy family. This is not a return in the common sense of the term. The whole venture involved the very real possibility of investing everything he possessed, only to enhance someone else’s estate. Mr. So-and-so did not hold the land in trust because he felt the risk was too great. He wanted the land all for himself or he did not want to have it at all. Hence, he gave Boaz the right to redeem the land and to take Ruth as his wife.

The Catch

At first it looked like purchasing the land would be a great benefit. Mr. So-and-so could have worked it, and he could potentially have reaped all the rewards. However, there was a huge catch—redeeming the land also required him to be a redeemer for Ruth. Notice that Boaz purposefully waited to reveal this to Mr. So-and-so. Boaz deliberately linked the land together with the levirate laws. The transaction and our whole story involved far more than a piece of land—this was about performing the duty of a younger brother as outlined in Deuteronomy 25. Hence, Boaz wanted to draw this man into a public rejection of his duties so as to seal the whole deal with witnesses in a court of law. There would be no doubt about who was Ruth’s true husband because of the way the man actually removed himself from the scene with his own words.

Notice how Boaz drew Mr. So-and-so into renouncing his claims with a kind of “Oh, by the way” statement. This piece of land needed to be purchased in order to keep the land in the family—the extended family. You will notice that Boaz didn’t mention Ruth at first. Rather, he spoke only of the land. “Then Boaz said, ‘On the day you buy the field from the hand of Naomi, you must also buy it from Ruth the Moabitess, the wife of the dead, to perpetuate the name of the dead through his inheritance.’ And the close relative said, ‘I cannot redeem it for myself, lest I ruin my own inheritance. You redeem my right of redemption for yourself, for I cannot redeem it’” (vss. 5–6).

If Ruth had one son by this man, the boy would have had Elimelech’s name, and he could possibly have gained this man’s inheritance if he had no more sons. Remember, the levirate laws require the firstborn son to belong to the older brother. This seems to imply that the rest of the children born to this family would belong to the younger brother. Hence, humanly speaking, it is a bit of a gamble. This could involve a huge investment and cost him in many ways. Likewise, there was a very real possibility of little and even no return for this man. There was always a calculated risk in every investment. This man simply thought that the risks outweighed the costs at this time. After all, his entire investment might be lost in one sense.

At this the man decided not to purchase the land. If the man bought the land, he would not get to keep it or pass it on to his own sons. Rather, he would purchase the land only to hold it in trust for the firstborn of the dead man. Any sons that he may have who would bear his name would not get the investment of the land. The firstborn son would bear the name of Elimelech, and the land would belong to Elimelech’s son. Consequently, this man’s firstborn son could possibly inherit the land, which he was now making an investment. Perhaps the risk was fine if he were assured of a long term return. Yet, with the very real possibility that this man might lose the land quickly, he reconsidered his investment. What if he had only one son? Then not only this piece of land, but all of the rest of his inheritance might have gone to Elimelech’s heirs.

The Hebrew language indicates that Ruth actually owned the land and was going to sell it. If it were just the land, then the man could have had the property all to himself. Perhaps he could have sold it at a profit. Maybe he saw this as a sheriff’s sale, and he was hoping to turn it around quickly. More than likely he could have purchased the land, developed it, and added it to his whole estate, and then he could have passed it on to his children as part of his inheritance at least until the year of jubilee. God had given the various laws regarding the land not so they could keep it forever. Rather, God tested the faithful—would they grasp after an inheritance of their own making, or would they trust in the Lord and give it back freely to the previous family?

It could have been that Naomi had rights to a portion of a common field in which many families shared. This would have made it very difficult for her to obtain it as a widow. It would have also made this man’s purchase a sweet deal. He could have increased his investment and he would have experienced an immediate return on the land at the next harvest. Samuel doesn’t record the exact details, but at least from Mr. So-and-so’s perspective, he thought he could make a one-time transaction and profit from the land, but there was a catch, and her name was Ruth.

I Cannot Redeem:

Boaz brilliantly maneuvered Mr. So-and-so into making the public proclamation: “I cannot redeem.” In saying this he removed himself from the scene. His words reflect the symbolic exchange of the sandal that takes place later. He was ready and willing to take the land when it was only the land, but when Boaz connected all the dots of his responsibility, he stepped aside willingly. This man’s response was a classically selfish response. He was not acting in selfless faith to the duty of the Lord. Like Elimelech, he was faithless. His actions remind us of Onan, in Genesis 38, who refused to perform the duty of the levirate for Tamar. These are the kinds of men who preferred a piece of land to the will of God. He was selfish and confused, grasping after something that would never preserve his name, and in so doing he removed himself from our story. Ironically Mr. So-and-so disappears forever as a nameless failure.

The Sandal

When Mr. So-and-so refused to carry out his duty, he was required to show this publicly by exchanging his sandals. Why a sandal, and what does this mean? As noted in the previous chapter, Ruth provides evidence of the levirate laws in action. We find some help from Deut. 25:7–10.

But if the man does not want to take his brother’s wife, then let his brother’s wife go up to the gate to the elders, and say, ‘My husband’s brother refuses to raise up a name to his brother in Israel; he will not perform the duty of my husband’s brother.’ Then the elders of his city shall call him and speak to him. But if he stands firm and says, ‘I do not want to take her,’ then his brother’s wife shall come to him in the presence of the elders, remove his sandal from his foot, spit in his face, and answer and say, ‘So shall it be done to the man who will not build up his brother’s house.’ And his name shall be called in Israel, ‘The house of him who had his sandal removed.’

Spits in his Face

The reader notices that Ruth’s story does not include the infamous “spitting in the face.” This is quite obviously an expression of contempt and shame. One need not possess tricky insight into the nuances of the Hebrew language—it is safe to say that spitting in someone’s face is a fairly universal action of scorn. Samuel conspicuously leaves this out of the sandal exchange in Ruth’s story. Ruth’s story also omits the woman’s removing of the man’s sandal, which was used as a symbolic action of shame. Because the man in Deuteronomy 25 refused to raise up seed for his dead brother, he was publicly humiliated as impotent. He was shamed as one who is unable to perform his duty as a levirate. It also indicated that this man refused to stand in his own shoes in regard to this responsibility. He deserved to be ashamed because he refused to maintain his obligations.

In Deuteronomy 25, the widow pulls off the man’s sandal, spits in his face, and declares his disgrace using a new name. Now most of us today don’t think of the name, “the one whose sandal is removed” as a blight on our reputation. It may sound a bit odd, but it doesn’t seem to carry the kind of intense humiliation that this procedure must have carried in ancient Israel. However, we should note that this was something very significant. “Now this was the custom in former times in Israel concerning redeeming and exchanging, to confirm anything: one man took off his sandal and gave it to the other, and this was a confirmation in Israel” (Ruth 4:7).

What Samuel recorded in Ruth’s story is not this kind of shame, but it does involve something similar. In our scene the reader should notice that there was no shame in the transaction, since neither one of these men was the younger brother. Hence, the handing of the sandal seemed to indicate that one man was transferring his obligations or responsibilities to another. It was as if to say, “You walk in my sandals in this matter.” The issue did not involve public shame connected to levirate refusal as in Deuteronomy 25, but it represented the idea of a transfer of duty and responsibility.

And Boaz said to the elders and all the people, “You are witnesses this day that I have bought all that was Elimelech’s, and all that was Chilion’s and Mahlon’s, from the hand of Naomi. Moreover, Ruth the Moabitess, the widow of Mahlon, I have acquired as my wife, to perpetuate the name of the dead through his inheritance, that the name of the dead may not be cut off from among his brethren and from his position at the gate. You are witnesses this day” (Ruth 4:9–10).

Boaz showed himself to be the responsible man. He stepped into the shoes of the kinsman redeemer and carried out his duty. Likewise, Boaz became the mediator between the deaths of the early part of our story and the life that is to come at the end. He opened the future to resurrection life.

Resurrection

As Ruth’s story concludes, perhaps the clearest theme of all is the idea of resurrection from the dead. In this final transaction the reader sees the dead raised to life. The names of the two deceased brothers were mentioned in reverse order from the earlier portion of the story. Samuel may have done this to remind us that Boaz’s actions reversed their deaths, and that through Boaz, God would bring new life to the family.

Boaz is the goel—remember that goel is the Hebrew word for kinsman redeemer. This was the family member charged with the responsibility of caring for the welfare of the family, even at his own expense. The redeemer would buy back land, pay debts, and set prisoners free. He would stand in the place of the helpless, or in this case, in the place of the dead. He stood for those who could not stand for themselves. The redeemer stood in the place of the widow and the orphan. The redeemer stood in the place of the helpless man who had fled to a city of refuge under the threat of death. The redeemer was the ultimate philanthropist, because his actions did not directly benefit him. The whole concept demanded a selfless love for others.

In Ruth’s story the redeemer was a lawyer—Boaz was the resurrection lawyer. The concept of goel involved the idea of prosecuting justice on behalf of someone who had no legal standing. He played the messianic roles of our Savior in so many ways. For example, Boaz stood as an advocate in a court case. Remember that the gate of the city was the ancient courthouse. Thus, Boaz was prosecuting justice on behalf of Naomi and Ruth. Boaz would not allow the first relative to take advantage of Ruth or Naomi. He stood as the advocate for these two helpless widows. In Ruth’s story, Boaz rightly combined the concepts of redemption and the levirate laws. Because Boaz stood in the gap, Mr. Selfish So-and-so was not allowed to take the land and run away from his responsibilities.

When the unnamed relative agreed to one part of his obligation, Boaz pressed the claims of Ruth according to the levirate laws. Whoever stood in the place of the redeemer also had marriage obligations that came with the land. He had to be a true husband who was concerned for his family and the land. Redemption as a concept was powerfully argued when it was melded together with the obligations of a redeemer and a husband.

Boaz advocated justice for Naomi as a widow with no apparent base of support from her family, because they had all died. Boaz also stood as the advocate for Ruth, a widow and a foreigner, who was in an even more precarious position. Boaz stood where these two women could not have stood on their own—he was their advocate.

Resurrection and new life propels us forward into the resurrection chain of blessings, which leads us directly to our Savior, Jesus. Indeed, our standing before God is commonly linked to a courtroom and throne scene. The judge looms over us as we are helpless, but God provides an advocate. Notice 1 John 1:9–10, “If we confess our sins, He is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all unrighteousness. If we say that we have not sinned, we make Him a liar, and His word is not in us.” Also, notice these words, “My little children, these things I write to you, so that you may not sin. And if anyone sins, we have an Advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous. And He Himself is the propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the whole world” (1 John 2:1–2). It is Jesus who pleads our cause and lifts us from our knees in condemnation to a position of one who obtains justice. He takes us as his own. He gives himself as our mediator and husband. We are his bride. The whole of the story of Ruth drives us forward to the story of Jesus. Yes, as we have said repeatedly, Ruth’s story is our story.

Jesus, the Ultimate Philanthropist

What Jesus does as our advocate cost him dearly. Indeed, our Savior gave everything with nothing to gain. Love from Jesus flows outward like the images of the rivers of water that flow from the temple in Ezekiel 47. He was punished so we would not be. He was lashed and beaten so we could avoid the beating we so rightly deserve. Oh Christian, do you appreciate his philanthropy? Jesus has given more than any millionaire has ever given to the cause of libraries, schools, or hospitals. He sacrificed himself for us, and it cost him everything.

Jesus was scourged and beaten, mocked and hated, but why? What did he do to deserve such scorn? What did he do to deserve the betrayal and the hatred? What did he do to deserve the crown of thorns or the nails that pierced his hands and feet? He gave himself entirely on behalf of sinners—he is the ultimate philanthropist. Listen to the well known but never too familiar prophecy of God’s philanthropy, of God’s love for sinners in Isaiah 53:4–8,

Surely He has borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we esteemed Him stricken, smitten by God, and afflicted. But He was wounded for our transgressions, He was bruised for our iniquities; the chastisement for our peace was upon Him, and by His stripes we are healed. All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned, every one, to his own way; and the LORD has laid on Him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed and He was afflicted, Yet He opened not His mouth; He was led as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before its shearers is silent, so He opened not His mouth. He was taken from prison and from judgment, and who will declare His generation? For He was cut off from the land of the living; for the transgressions of My people He was stricken.

What a contrast! We see the selfish, unnamed relative evanescing into the vaporous halls of history’s unknown. The selfish man who struggles and strives to protect his name is never named and disappears forever. Only the philanthropist remains! Only the one who gives his life to God and neighbor will have an eternal inheritance. He through Christ will have an everlasting name.

Where are you in this story? Are you struggling desperately to preserve what can’t be preserved by your own efforts? Or will you be like Ruth, who longed to be covered by Boaz? If you will come to Christ, as Ruth came to Boaz, then you will encounter the ultimate philanthropist, and you will find the ultimate love!

Questions for Consideration

1. What is philanthropy? Can you give some examples?

2. What is the significance of the city gate?

3. What is the significance of the name, “Mr. So-and-so?

4. Why does Ruth’s story omit the “spitting” of Deuteronomy 25?

5. Why do Boaz and Mr. So-and-so exchange sandals?

6. How was Boaz an advocate, and how is this like Jesus?

7. Do you agree that Jesus was the ultimate philanthropist? Explain.