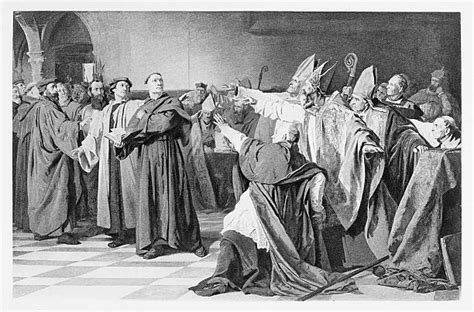

On October 31 it was 448 years ago that the monk, Martin Luther, posted his 95 theses upon the door of the castle church in Wittenburg. In itself it was a rather insignificant fact. It just meant that a young theological professor invited his colleagues for a dispute on certain theological issues. In reality, however it became the starting point for a new theological and ecclesiastical movement that decisively changed the whole face of the Western Church. Up till this very day the impact of this fact is still being felt.

At the same lime, in our day, we hear an increasing number of voices asking: Is it still necessary to hold on to those decisions of the 16th century? There are even voices that say: Actually it was not necessary in the 16th century either. They speak of the Reformation as a “tragic mistake,” which never should have happened. However, the number of the latter voices is not very great. Most Protestants would still agree that the Reformation in the 16th century itself was an historical necessity. Even many Roman Catholics admit that the situation in the Church of Rome of the 16th century was such that something had to be done.

Of course, they still regret the fact that Luther’s action led to a schism in the Church; they also are critical of Luther’s theology, but they do admit that the inner corruption of the Church had reached a stage which made some kind of reform inevitable.

But what about today? Is it still necessary to continue the old controversy? More and more Protestants seem inclined to answer this question in the negative. They believe that the time has come to remove the old barricrs. In fact, they believe that many of the old barriers are not real or relevant any more.

Important Changes

On either side of the old dividing line there have been important changes. Home has changed and shows a real appreciation of the truths rediscovered by the Reformers of the 16th century. The Churches of the Reformers have changed, also, and admit that on many points the theology of the Reformers was determined by reaction, the result being that the fulness of the Christian truth was not always seen by them.

Take, for example, the problem of the relation between Scripture and Tradition. In the 16th century there was a wide gulf on this point. The Reformers emphatically declared that Scripture is the only source of revelation and norm of faith. Over against them the Council of Trent declared that the truth and discipline which Christ proclaimed with his own mouth are contained “in written books and unwritten tradition’s,” which arc to be received and venerated “with equal pious affection and reverence.” In this century, however, the situation has changed. While Trent seemed to teach two parallel sources of revelation, the Second Vatican Council has declared that there is but one source of revelation, viz., the Gospel of Jesus Christ, which comes to us through two different channels—namely the Bible and the apostolic tradition. At the same time many Protestants are willing to accept traditions, not as an additional source of revelation, but as a helpful, and even authoritative, interpretation of the original revelation. In other words, the parties have come much closer together.

Furthermore. it is said, we can no longer afford to continue this struggle within Christianity itself. We are living in days in which Christianity as a whole is threatened by dangerous and mighty foes. Secularism, nihilism, Communism, etc., are slaying. their thousands and ten thousands. In the heathen world we see a strong revival of the old religions. In such a situation there is no time for a “civil war” within Christianity itself.

I believe that it is worthwhile for us as evangelicals to listen to these voices, and ask ourselves the question: Is the Reformation still a living reality today? If it is not, we had better stop our commemorations on or around October 31. If it is only and purely an historical affair, we should use our time for more necessary things. A commemoration, especially an annual commemoration, is meaningful only when the fact that is commemorated is still relevant for our own day.

In these articles we intend to answer these questions by first studying the relation of the Church of Rome to the Reformation, and then also the situation in the Protestant Churches themselves.

Changes In Rome

There can be no doubt that i.n recent years much has changed in the Church of Home. I only need to mention the fact of the Second Vatican Council. A few years ago sueh a Council would have been deemed impossible.

To a large extent this change is due to one man: Pope John XXIII. On purpose I wrote, “to a large extent.” It is evident that he could not have accomplished such a change if there had not been a kindred spirit in large sections of the Church itself. In fact, for many years there was an ever growing progressive party in the Church. But before John was called to the highest office in his Church, this party had hardly any influence upon the administration of the Church. The Roman curia, in particular, was strongly traditionalist in outlook and action. But then John came, and almost overnight the whole situation changed!

There is something of a mystery in the appearance of this man. He had been Pope for a few years only, and yet he changed the face of his Church completely. Many books have been written about him, but no author has yet been able to explain this mystery fully. He was chosen as a “papa di passagio,” a “transition Pope.” Apparently the cardinals could not agree on anyone else at the time. He was an old man, well in his 70s, an age when most people have become rusty in their thinking and set in their ways. Yet he became the greatest innovator of his Church in modern times.

Some have called him “a political genius.” So Robert Kaiser, in his book, Inside the Council, said: “Behind his action, with their political resonances, there lies an intuitive grasp of the geopolitical situation in our world” (p. 4). Others called him “the pastoral Pope with his childlike devotions.” Cardinal Heenan of Westminster wrote in 1964: “Pope John was the old-fashioned ‘garden of the soul’ type of Catholic…He was not an original thinker…He was no innovator … he was responsible for no great reform. His great achievement was to teach the world of the 20th century how small is hatred, and how great is love” (quoted by E. E. Y. Hales, “Pope John and his revolution,” 1965, p. 3). Which of the two is right? It is hard to say. But one thing is certain: Pope John was “sui generis,” an unique phenomenon, and his brief reign was cataclysmic.

All, both Roman Catholics and Protestants, also agree that he was a “bonus pastor,” a good pastor. Both words should be emphasized. He was a real pastor, full of concern for people, not only those belonging to his own Church, but also those outside this Church. He wanted to be a pastor to the whole world. He also was a good man. He had a deep and real love for his Master Jesus Christ. One only needs to read his diary, published after his death: “The Journey of a Soul”—how different is this from the situation in the days of the Reformation!

The Westminster Confession speaks for the situation of its day when it says in Ch. XXV, section vi: “There is no other head of the Church than the Lord Jesus Christ, nor can the Pope of Rome in any sense be head thereof; but is that antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalteth himself in the Church against Christ, and all that is called God.” I know, of course, that this statement is not meant as a judgment of the person of the Pope but rather of his office. But even so, the changes that have taken place are striking. I really wonder whether the Westminster Divines would have saith the same if they had known a Pope such as John XXIII.

Thanks to John, after more than 90 years, a new Council was convened in Rome, and it became one great surprise, even for the Roman Catholics themselves. For the majority of the bishops appeared to be progressive. I do not think that they all were progressives already when first coming to Home. But once present at the Council, the majority of them was caught by the progressive spirit. Some of the most progressive theologians (a.o. Karl Rahner) were appointed as official advisers of the Council fathers.

Karl Barth’s Evaluation

All this meant a very great change. In a recent interview dealing with the relation between Rome and the Reformation, Karl Ruth has said: “Since Rahner, Church of Rome and the Reformation Churches” (published in Christianity Today earlier this year). A reader, who called himself an evangelical, afterwards in a letter to the editor protested against the sentence: “There is no place for Mary or the saints in the divine scheme of salvation.” The reader called this “a direct affront to evangelical faith.” His argument was as follows: “Granting that Mariolatry became a great bone of contention and still is, and recognising that the Roman Church is re-affirming the centrality of Christ as the one Mediator between God and man, do we not as evangelicals recognise that the salvation of men involved Man as well as God? And that Mary’s assent to be used by God the Holy Ghost, giving men this way, credit so to speak, for their free will, was essential to the Incarnation? Once the break was made by Adam God had to find a human being who would freely consent to H is entry into human nature, and this was the Blessed Virgin Mary. It was ‘in man, for man’ that God fought the foe, and without her opening freely the door a real incarnation—God become really man—could not have happened, because that essential quality of man (and of evangelical faith), namely, free will, would have been destroyed. Where is the evangelical faith without the appeal to a free consent to Christ’s discipleship?”

I was rather startled to read this, in particular as the writer claimed to be an evangelical! For this construction—Mary co-operating, on behalf of mankind, with God—is the real heart of the R.C. Mariology. This was exactly the protest of the Reformers against the n.c. doctrine of salvation! In their view this construction meant the end of the doctrine of free grace. Evangelicals should beware not to introduce the essence of the R.C. doctrine of redemption into their dogmatics by an un-Reformed doctrine of free will. Once this has been accepted, especially in the Mariology, one cannot resist the rest of Mariology, namely, Mariolatry, the veneration of Mary (and the other saints). This is only a logical consequence.

(To be continued)

For some years to come Protestant church leaders and members will engage in evaluating the impact of the decisions of the Second Vatican Council which concluded its sessions last fall. In this article Dr. Klaas Runia, professor at the Reformed Theological College at Geelong (Victoria), Australia, begins a series intended to alert us that the issues involved in Rome versus Reformation have not yet been settled.