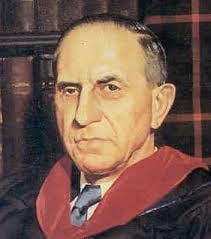

John Murray was born in Badbea, Magdale, Scotland, on October 14, 1898. We think of him today, therefore, on the one-hundredth anniversary of his birth. Thousands know him through his writings, especially Redemption Accomplished and Applied (1955); Principles of Conduct (1957); and his commentary on the Epistle to the Romans (1959, 1965). Since his death on May 8, 1975, a further treasure of his writings has appeared in the four-volume Collected Writings of John Murray published by Banner of Truth Trust. His widow, Mrs. Valerie Murray, made available the manuscripts printed in this collection. Dr. lain Murray, the editor, also included in the third volume a biography of Westminster’s Professor of Systematic Theology.

Through the recollections and research of the Rev. Geoffrey Thomas of Aberystwyth, Wales, you will soon be treated to a study by one whose life and ministry is itself a moving tribute to the one who was his mentor. My privilege is to recall with you John Murray as a man of prayer.

RECOLLECTIONS OF JOHN MURRAY’S PRAYERS

All who heard John Murray’s classroom lectures will remember his prayers that began the lecture hour. I had some faint hope that a few of his recorded lectures might include the prayers with which they began.

But although Westminster Media in Philadelphia searched the recordings they have on file, they could not find a single example. “Perhaps they were removed in the editing,” it was said. I think not. John Murray himself would have seen to it that no recording of a prayer would have been made. His personal adoration of the triune God, and his petition for the illumining work of the Spirit prepared him for his labor in the Word at that time and place, and with that subject on his heart. In prayer, he stood before the throne, and not before a class.

Students who were led in these classroom prayers observed how often John would begin in hushed reverence, humbled before the majestic glory of the living God upon whom he called. Adoration brought confession of our sin and unworthiness. Then, emboldened by the sure promises of grace, his voice rose toward heaven with the wonder of the finished work of our Mediator. the glories of His heavenly ministry and of the Father’s saving plan. Indeed. the pattern of his prayer was often echoed in the lecture, where ringing proclamation of God’s truth climaxed the hour. (l am not sure that this came at the very end of a lecture, but I can still hear a John Murray climax: “No known or predicted eschatological era separates us from our hope.”)

John Murray ministered to me personally on many occasions. His Collected Writings include a charge he gave me when I was installed as Professor of Practical Theology at Westminster on October 22, 1963 (Writings, vol 1,pp. 107ff.). Much earlier, in 1942, he preached the sermon on my ordination to the gospel ministry in New Haven, Connecticut. That sermon, too, is in his writings, entitled “The Call to the Ministry,” Jeremiah 1:5–7 (Writings, vol. 3, pp. 172–177). I now regret that John did not give me a copy of his manuscript, for I see wisdom that my memory failed to store. His text stayed with me, as did his emphasis on the electing choice of God’s love. But these words I wish I had memorized:

The sacred office has its peculiar temptations, temptations sometimes to arrogance and pride, and sometimes to doubt and fear and crushing depression of spirit. The antidote for such fluctuating billows of temptation is to carry in the forefront of memory and conviction that fountain of eternal love that is not susceptible to the fluctuations of our experience, but which is an overflowing and even-flowing stream of grace to promote humility and to refresh our souls against the perils of debilitating melancholy. ‘Before I formed thee in the belly I knew thee.’ (Writings, 3:173.)

The application of those words to prayer is evident.

I vividly remember John’s glancing at me when he came to Jeremiah’s response, “Ah, Lord God, behold, I cannot speak: for I am a child.” I had no trouble identifying with Jeremiah although I had much to learn about how much I had to learn. As always, John was faithful to the text, and charged me not to soften the stroke of God’s Word to spare people’s feelings, but like Jeremiah, to go “to all that I shall send thee, whatsoever I command thee thou shalt speak.” John’s sermon ended on that stern note. The next Sunday morning my first duty as the new pastor was to install a man who had been elected a deacon, and to discover that, in the judgment of charity, he was a convinced Arminian. When I explained that, believing as he did, he could not possibly make the vow that he was scheduled to take, he stalked out of the room and out of the church.

Yet I must confess that I was sterner by far with the liberal enemies of the gospel outside the Orthodox Presbyterian Church than with the sins of those to whom I ministered. I preferred to draw men to Christ rather than drive them, but I lament my lack of John Murray’s sternness in exposing sin. Yet John’s warnings always pointed to the glory of sovereign grace.

So much more could be harvested from my memories of John as my teacher and colleague — not least the astounding ease with which he accepted this child in the roles I was given at Westminster. But I must speak, not of John as a man, but of him as a man of prayer.

Here, again, more memories crowd in. In a time of devastating personal grief concerning a member of my family, I sought John Murray to request his prayer. We sat together in the library of Machen Hall, then the faculty room. As John interceded for me, and for the deepest concern of my heart, he prayed with urgency and strength, weaving together passages of Scripture to form the fabric of his claim on the mercy and promises of God. At that moment, I confess I was overwhelmed with the sheer blessing of having such an intercessor to take me before my heavenly Father. Then, as his prayer was lifted to the mercy-seat, he began to thank the Father for the mediation of God’s eternal Son, the merciful and faithful High Priest, who ever lives to make intercession for us. Then it came home to me. I had a better Intercessor than John Murray. Jesus Christ my Savior prayed for me.

I will not try to describe the prayer of John Murray at the funeral of my mother, whom, of course, he knew.

In my one extended visit to Scotland, I was driven through much of the country to speak at “Wee Free” churches, including a number in the highlands of Scotland. We did visit Mrs. Valerie Murray and their son Logan at Bonar Bridge. In the highlands, and particularly at Inverness, I had the opportunity to meet some of the leading pastors of the church. For their training of candidates for the ministry, they chose pastors known for their piety and for their expertise in some branch of theological and pastoral study. A candidate would live with one of these pastors, usually in his home, assist in the ministry and be instructed in New Testament, Old Testament, Theology. Church History, Homiletics and other disciplines, all in the midst of pastoral service. When these pastors prayed, I knew that Ihad heard prayers like that only from John Murray. Many of his emphases in prayer were supported by that highlands tradition of reverent and importunate calling upon the Lord of glory and grace.

Although John Murray spoke of prayer as a means of grace (Writings 3: 169), his published lectures do not deal systematically with prayer. He has a sermon on “Prayer” based on Psalm 116:1, 2 (Writings 3:168). In that moving message he preaches exegetically with his usual faithfulness to the text. Rich as it is, it does not summarize his thought on prayer. His best-known writing on prayer is the Campbell Morgan Bible Lecture for 1958. delivered in Westminster Chapel. London: “The Heavenly, Priestly Activity of Christ.” Of course, many other places in his writings bear testimony to both his teaching about prayer and his life of prayer. His commentary on Romans is particularly rich, as we shall see.

(To be continued next month.)