He died as he had lived, trusting the promises of the Lord! Three weeks before his last day he wrote these words to his old comrade-in-arms, Farel: “It is with difficulty that I draw my breath, and I expect that every moment will be my last. It is enough that I live and die for Christ, who is the reward of his followers both in life and death.”

Then came the end on Saturday, May 27, 1564. He was buried somewhere in the Genevan cemetery, but, according to his express wish, no stone was erected above his bones, and “no man knoweth his resting-place until this day.”

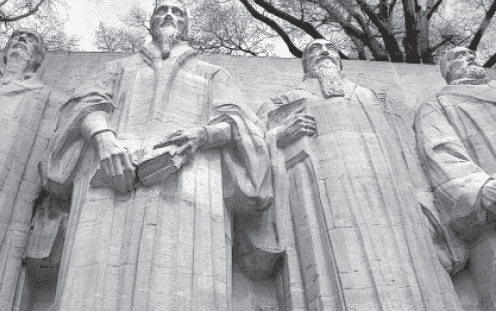

Who was this man who lived and died in the utmost simplicity, who had no children, but who could declare, “. . . that he had offspring in thousands over the whole of Christendom”? We write of John Calvin, the last of the great reformers, the church-father of Reformed and Presbyterian Christianity. Four centuries have now passed since his death.

It is impossible to sketch in a short essay his character, theology and influence. He has been praised beyond measure and slandered beyond measure.

He has been called ‘the Caliph of Geneva’ (Audin, Spalding). He has also been called ‘a character of great majesty’ (the Genevan Little Council). A man, who was certainly not a Calvinist, declared of him: “Among all he accomplished most, because he was the most Christian among all, yea the most Christian man in Christianity” (Renan). Calvin himself would have protested those last words of praise; he was a very simple man indeed, even somewhat shy. At no less than three occasions in his life, he had to be brought to his God-appointed place by a kind of ultimatum (Geneva, Strasburg, Geneva again).

His heart longed for friendship and work; the friendship of a gentle soul as Melanchthon’s; and the plain and hard work of a scholar at his study. But the hand of the Lord brought him in the midst of the spiritual battlefield of his time. If ever there was a predestinated man, called to a great purpose, then it was John Calvin.

What was that time in which he lived?

We can call it the crisis of the Reformation. When Calvin initiated his work in Geneva (1536), Zwingli had died, and the reformer of Basle, Oecolampadius, had followed him into the grave. The Swiss reformation seemed to have come to a standstill. Luther would die some years later (1546), and the morality of the Lutheran countries still left much to be desired; the Lutheran theologians were divided among themselves, and Melanchthon was an uncertain man, certainly not a convinced leader. The anabaptistic revolution had stamped all reformation-work as a fantastic fallacy, and in the Netherlands this new movement was smothered in blood. In France many were burned at the stake. In England Henry VIII tried a strange type of reformation in harmony with his personal wishes. In Germany Charles V pursued the aim of repressing Protestantism in a very astute manner, and the Counter-Reformation began its work in the Council of Trent and the first endeavors of the Jesuits. This was the time of John Calvin, and it seemed to be most probable that the young flower of the Reformation would be crushed under the feet of many enemies; that this movement would be shipwrecked as had been the movements of the Hussites and the Wyclifites two centuries earlier.

But God in His providence had decided otherwise. He raised up the reformer of Geneva, who completed and perfected the work of his predecessors and was blessed with the progress and extension of the Reformed faith not only in Switzerland and France, but also in the Netherlands and parts of Germany, in England and Scotland, in Poland and Hungary, and finally in America and throughout the world.

How did he succeed in such an astounding enterprise?

We can only answer: with the help of God and as an instrument in His hand. Calvin did not make Calvinists, but God prepared the hearts for the message of the pure gospel. Is, then, that message of Calvinism to be identified with the pure gospel? Not as far as Calvin and the Calvinists are concerned, who were and are only imperfect human beings. They should always repeat the device: ecclesia reformata, quia semper reformanda (a reformed church, because it should always continue in reforming). Not as far as any theological work of Calvin is concerned which is, after all, only human and fallible.

But certainly, as far as the aim and purpose, the heart and core of this theology is concerned. It aims only at bringing the pure gospel, reformed, stripped of all human additions.

Let us take a look at it. Then we are struck first of all by the prominence which Calvin conferred on the Word of God. Often he has been accused of having framed his Calvinistic system of doctrine as the logical conclusions of one religious or philosophical principle. But Calvin was not in the first place a systematizer or a dogmatician, but an exegete, an interpreter of Scripture. His Institutes are the systematic exposition of that doctrine which he found in the prophetic and apostolic books of the Old and New Testament. Calvin expressed himself in no uncertain terms:

This is the difference between the apostles and their successors: the former were sure and genuine scribes of the Holy Spirit, and their writings are therefore to be considered oracles of God; but the sole office of others is to teach what is provided and sealed in the Holy Scriptures (Inst. IV, VIII, 9).

As a matter of fact, all the reformers acknowledged the sole authority of the Bible. But with Calvin we find a kind of intrepidity and consistency which made him take all the words of Scripture seriously. When Scripture spoke of human depravity, he did the same; when Scripture made mention of God’s predestination, he followed that line without hesitation; when Scripture spoke of the necessity of regeneration, he stressed that point; when Scripture emphasized human responsibility, he did the same, and asked absolute obedience to God’s commandments.

Calvin was therefore, in the second place, the man of the fear of God. His last words to the Syndics and Senators of Geneva, spoken on April 27, 1564, were: “I again entreat you to pardon my iniquities, which I acknowledge and confess before God and His angels, and also before you, my much respected Lords.”

That expression “before God and His angels” is a repeated expression in his letters and treatises. He always is mindful and makes others mindful of the presence of God. He has been called “the messenger of that Jehovah who had appeared to Moses upon Mount Horeb and who, in their wanderings, had gone before the children of Israel in a pillar of fire” (Carew Hunt). Another author compares him with Moses, who had seen God and whose face shone by the brightness of God’s glory, and adds: “The same must repeat itself inwardly with him who, as Calvin did, looks upon God daily and does not turn his eye from his face” (E. Stahelin).

Because Calvin was the reformer of the fear of God, he was also the man of the glory of God in human life. Not only man’s soul, but also his head and hand should praise the Lord. Not only the psalms in church, but also the science of the scientists should honor Him. Not only the clergy, but all the citizens of Geneva should obey their Lord in their threefold office as prophets and priests and kings.

Calvin shared with Luther the central doctrine of justification by faith only; he declares that the sum of the gospel embassy is to reconcile us to God, since God is willing to receive us into grace through Christ, not counting our sins against us (Inst. III, XI, 4). Yet his final aim is not the salvation of souls, but the honor of God in all spheres of life.

He has often been accused of being the dictator of Geneva who ruled and reigned with an iron hand. This accusation is not true. During a period of several difficult years, he found a council of hostile citizens against him. He had to fight the battle of his life in order to obtain real freedom for the church. As a matter of fact, the strict laws of Geneva requiring a sober and modest life and forbidding dancing, cursing, luxury and all forms of Romish superstition were to be found in other Protestant cities also.

But the difference was that in the city of Calvin those laws were enforced; in other cities they were often dead letters. Calvin wanted them to be taken seriously, and he succeeded in the time of some twenty years to transform Geneva from a most frivolous city into the model-city of the Reformation, in which the fear of the Lord was the beginning of wisdom.

In the fourth place we should stress Calvin’s ecumenical position.

He has been called—and rightly so—the one international reformer. It is a well-known fact, that his simple house in Geneva became in due time the headquarters of the Reformation-movement. His correspondence embraced a large part of Europe, while he gave leadership to churches in several countries. He approached the Lutheran churches and admired Luther as a father in Christ; he was the close friend of Melanchthon and contacted Bullinger, the successor of Zwingli in Zurich, and succeeded with him in unifying the Swiss Reformed churches. He even desired a general council of all Protestant church leaders, not to engage in permanent dialogue, but to frame and define a common confession of faith founded on the Word of God.

He wanted a real union and not a sham union. Therefore he warned with all his heart against compromise with Rome; and also against closer relations with the Anabaptists and Socinians, the liberals of that day. He did not like the maneuvers of his friends Bucer and Melanchthon, who were inclined to express themselves in vague terms and glib formulas. He warned against the interim policy of Charles V, who tried to seduce the Protestants. He wrote to the kings of England and Poland and other high placed persons, that they should take a firm stand and purge their churches from all papal idolatry, making them truly reformed churches.

We might conclude by saying that Calvin wanted a real church. In his own life he showed much reverence for the church, as long as possible, even in a corrupt or disorderly state. He hesitated long before he left the Church of Rome. Only God’s own hand could convince him of the lawfulness of that step after the experience of his subita conversio (sudden conversion). And after his expulsion from Geneva he did not allow his followers to establish separate churches; he hated schism and wrote “that the ministry and sacraments should be held in such reverence that wherever they perceive them to exist, they should judge the Church to be.”

Therefore he wanted one church of the Reformation, only one church. But it should be a real church, the purity of which was evidenced by the faithful use of Christian discipline. It has been questioned whether Calvin (as several Reformed Confessions do) considers this use of discipline to be one of the marks of the church. It is unquestionable that he fought the struggle of his life to get and maintain it. In 1538 he was expelled from Geneva because he refused to administer the Lord’s Supper without the proper use of discipline. During the second period of his ministry there he wrestled for years to establish that discipline.

“As the saving doctrine of Christ,” he said, “is the soul of the church, so does discipline serve as its sinews, through which the members of the body hold together, each in its own place. Therefore, all who desire to remove discipline or to hinder its restoration are surely contributing to the ultimate dissolution of the church” (Inst. IV, XII, 1).

In the exercise of discipline Calvin stresses moderation and mildness. He does not carry the idea of a pure church too far. Well known are his words: “The pure ministry of the Word and the pure mode of celebrating the sacraments are, as we say, sufficient pledge and guarantee that we may safely embrace as church any society in which both these marks exist. The principle extends to the point that we must not reject it so long as it retains them, even if it otherwise swarms with many faults. What is more, some fault may creep into the administration of either doctrine or sacraments, but this ought not to estrange us from communion with the church. For not all articles of true doctrine are of the same sort” (Inst. IV. I, 12).

The positive contribution of Calvin to the work of the Reformation on this score has been that he settled the freedom of the church to arrange its internal affairs by means of its own consistory. Luther had taken refuge in the princes of Germany, who assumed the task of organizing the several churches and of appointing governmental consistories. Zwingli had called upon the magistracy of Zurich to rule the church. Consequently discipline in the Lutheran and Zwinglian churches had not been maintained in purity. It was Calvin’s ideal to have a free church in a free city, although in his days the power of the government of Geneva over the church was still great, and even the elders were not appointed after a free election by the people but by the councils of the city. Calvin’s ideal was a church governed only by its own office-bearers and (in France) by its own minor and major assemblies; a church fundamentally only governed by its Head Jesus Christ and free from all interference by the state.

It is difficult to say whether Calvin was the man primarily of the right organization of the church, of the personal fear of the Lord, or of the subjection of all areas of life to God and His Word. However that may be, we honor him as a chosen vessel of God, an instrument in the hand of the Almighty who gave him at the right time to His church.

We conclude with the words of his friend and successor, Beza, penned at the end of his Life of Calvin: “I have been a witness of Calvin’s life for sixteen years, and I think I am fully entitled to say that in this man there was exhibited to all a most beautiful example of the life and death of a Christian, which will be as easy to calumniate as it will be difficult to emulate.”

Rev. Louis Praamsma (1910-1984) served several churches in the Christian Reformed Church. He also served as an Assistant Professor at Calvin Theological Seminary.