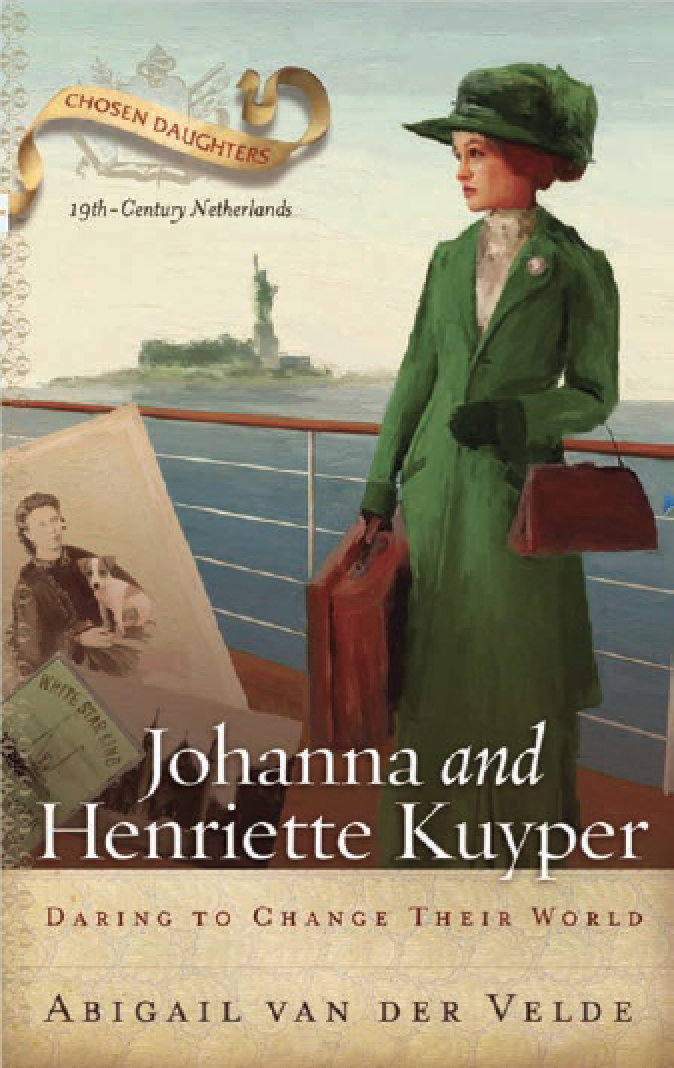

Their World, by Abigail Van der Velde. Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2017. 268 pages. $10.00 (and various prices online).

Lately, it seems impossible for me to escape: whether I open my business LinkedIn page, pick up a newspaper, or stick around long enough to watch a television commercial, there’s now always a celebration of women in high-ranking positions who have “leaned in” to become “leaders” in their fields. Along with this, of course, is the flip side of the coin: the complaint that there are still not enough women CEOs, high-ranking government officials, or international movers and shakers.

This is nothing new, but the clamor for female leadership, whether in business or government, seems to have gotten both more frequent and shriller since Hillary Clinton lost the presidential election in 2016, and Facebook executive Sheryl Sandberg published and built an organization around her book, Lean In, a how-to for women to lead in our society and culture.

It’s refreshing, then, to read about a Christian woman who knows her own mind, a relatively well-educated one for her time at that, who is, firstly though not only, dedicated to her husband and children. Such a woman was Johanna Kuyper, wife to Abraham, as portrayed in this historical novel. Johanna (“Jo”) is shown to be submissive though far from servile, an effective manager of a busy household who is much more than a housekeeper, and a counselor and godly example to both her children and husband.

A Woman’s Gifts

Mrs. Van der Velde’s book is part of P&R Publishing’s Chosen Daughters series. Several Christian publishers have introduced such novels, portraying women, often behind famous and highly gifted men, who themselves are gifted and learn to use their gifts in the wider world even while serving as mothers and helpmeets. Such novels are fun to read as they paint historic backdrops for us, while also serving as instructional encouragement for Christian young ladies who still have much before them.

Mrs. Van der Velde’s portrayal of mid-nineteenth-century Rotterdam with its bustling harbor and cobblestone streets is memorable, as are her descriptions of the family life of the Schaays, Jo, Jo’s parents and siblings—from the rambunctious boys to the nineteenth-century women’s dresses and fineries. Jo met Abraham Kuyper (“Bram”) while on an outing at a distant town fair with his sisters, an event her aunt organized. Mrs. Van der Velde captures Jo’s excitement behind her propriety with the attention Bram pays her. The young Kuyper is portrayed as energetic, richly (though graciously) verbose, and intent on pursuing Jo. He wins Mr. Schaay’s approval to visit several times, after which a five-year courtship begins, which ends with Jo and Bram marrying when she turns twenty-one.

Jo k eeps a “workbook,” a place for her thoughts, lists of to-dos, and miniature artistic creations. It’s here, but also in her imagined interior monologues, that the author shows the teenaged Jo’s girlish though not improper thoughts. After she marries, these interior monologues mature, becoming less about herself and more about others, or shift entirely into prayer. Most of the book imagines Jo’s life between the age of sixteen, when she first meets Bram, and her wedding day. Later chapters jump years at a time, as more children fill the Kuyper household and Bram starts thinking biblically through, and acting on, different social improvements, to which Jo adds her input.

eeps a “workbook,” a place for her thoughts, lists of to-dos, and miniature artistic creations. It’s here, but also in her imagined interior monologues, that the author shows the teenaged Jo’s girlish though not improper thoughts. After she marries, these interior monologues mature, becoming less about herself and more about others, or shift entirely into prayer. Most of the book imagines Jo’s life between the age of sixteen, when she first meets Bram, and her wedding day. Later chapters jump years at a time, as more children fill the Kuyper household and Bram starts thinking biblically through, and acting on, different social improvements, to which Jo adds her input.

A Woman’s Ministry

In its entirety, the book is about three generations of women: Mrs. Schaay and her friends at church; Jo and her sisters, especially her older sister, Hennie; and later the Kuypers’ oldest daughter, Henriette (“Harry”). Mrs. Van der Velde shows these women to be concerned about the needs of others as well as their own lives and households. Mrs. Schaay, along with Jo and her sisters, are part of a women’s group that re-sews discarded clothes left at the church for the poor. Jo, the mature Mrs. Kuyper, managing a burgeoning household of her own, finds a way to rescue an overworked and poorly fed housemaid from neighbors to bring the young woman into her own employ. And Harry, who never marries, becomes, among other things, a children’s advocate in Russia and Hungary and a leader of Holland’s version of the Calvinettes.

The Kuypers’ problems are not whitewashed, though not fully developed either. Willy’s, their youngest son’s, death from a bacteria infestation, perhaps a version of E. coli, is realistically and remorsefully portrayed by the author. The Kuyper boys, as they become young men—Guillaume in particular—live uncomfortably in Kuyper’s ever-extending shadow cast by his growing notoriety, and as the years pass, a shadow instead of the man seems to become more evident, as Kuyper’s travels take him not only around the Netherlands but throughout Europe and around the world over long periods of time.

There is dialogue, especially between Bram and Jo, about some of Kuyper’s projects—government-sponsored Christian education and labor reform in particular. These views wouldn’t wear well with us here today, but to understand the impetus behind them in nineteenth-century Holland, they need to be placed in context: The division between secular and Christian education would, of course, be unacceptable to Kuyper, who saw all education as necessarily Christian. At the least, then, Christian schools should have the same advantages and resources as government schools, so poorer families that want a Christian education for their children could have one.

A Different Time

Also, poverty in nineteenth-century Europe cannot be compared with what we call the poor today here in North America. There was no welfare state at all then. Ruin and homelessness could be around the corner if a farmer’s herd of cows contracted a disease or if the farmer suddenly died, leaving behind a wife and children. Wages were low, and for young women there were often no wages at all, just room and board. Hours were long and grueling, especially in the cities where people flocked to escape rural poverty, and opportunity for the poor to rise above their circumstances were virtually nonexistent. It’s into this milieu that Kuyper spoke, not as a socialist, but as a Christian invoking love of neighbor, especially to businessmen who lived pampered lives while paying little to their workers, and not creating much opportunity for them to improve their lot either.

If we grimace somewhat at Kuyper’s promotion of labor unions and government-sponsored Christian education, it’s because our history is different from that of nineteenthcentury Holland: Labor unions here have contributed to the stifling of our industrial competition and have a history of corruption and even mafia involvement. Most of us would say “No thanks” to government sending money to our Christian schools, fearing, rightly, future strings attached. But that wasn’t the case in Kuyper’s Holland, and of course as energetically brilliant as he was, he did not foresee how bad ideas are really good ideas turned bad.

Mrs. Van der Velde portrays Mrs. Schaay, Jo, and Harry, three generations of Christian women, each with a more expansive sphere of influence outside her own household than the woman from a generation before: Mrs. Schaay is busy at home and at church, for the church but also for the community through the church; Jo as the mature Mrs. Kuyper is the same, but also has an eye and heart for young women around her, even ones who don’t necessarily attend her husband’s preaching; and Harry, a single woman, expands a ministry to children but also ministers among the war wounded and women in general, internationally.

What about Harry?

Henriette Kuyper, the Kuypers’ oldest daughter, gets a scant few chapters at the end of this book compared with her mother, Jo, but they are filled with activity, all of it directed outwardly toward others. She is a Red Cross volunteer, working with the wounded during World War I, but also with a children’s orphanage in Budapest, while at the same time serving as a war correspondent to Dutch newspapers. She is a writer and speaker at women’s groups and conferences throughout Europe and eventually America, discoursing on Dutch history but also other historic topics, wanting to help women expand their thinking and worldviews. The daughter of Holland’s former prime minister, she is the guest of President William McKinley but also of John D. Rockefeller—the means for helping the poor residing, as it did during the Gilded Age, only with wealthy philanthropists.

Her father didn’t like Harry addressing assemblies, even if they were comprised only of women—it didn’t seem right—but he eventually reconsidered and changed his mind as he neared the end of his life. Harry was a “lean in” woman in her way and in her time, not advocating for women’s boardroom seats but for them to be able to vote in elections (as her father had years earlier for congregation members regarding church business) and, though it wasn’t an obsession with her, for the right of women to run for political office (not prime minister, but seats in parliament).

Mrs. Van der Velde has Harry say at the book’s close to an assembled group of Christian women, “The Bible shows us that God called women to positions of leadership . . . Deborah, a prophetess and judge in Israel, made decisions that affected her people for good. Deborah is a model for any woman who allows the Spirit of God to shape her life.” Did Harry really say this? This can’t pass without a gloss. As true as these words are, there is a reason for Deborah’s leadership, and it’s not a good one. Actually, her position is a judgment, not on her but on God’s people (Isa. 3:12) for what the male judges should have done but didn’t. God’s means, even the unexpected ones, are always justified, but they may signal that something bigger is not as it should be.

Accurately Portrayed

Though she is an experienced writer, this is Mrs. Van der Velde’s first book, and it’s a historical novel, not a biography. Nonetheless, she has done her homework. Events are replicated with a helpful timeline provided (not to mention a recipe for traditional Dutch apple pie), historical geographies are researched and accurately represented, and Mrs. Van der Velde was able to access correspondence between Jo and Bram. Broadly, the narrative is historically accurate even while on a relational basis between characters, it’s pure—though reasonably believable—invention.

The novel is, however, imbalanced. Half of it occupies the Kuypers’ courtship (of interest to a young teenaged Christian girl, no doubt), but it speeds up, skipping years at a time, and compacts most of their years together that follow. Harry is the subject of a short, factual, but also inventive biographical sketch. What’s more, Bram’s conversion to the faith, even as he’s steeped in theological studies at Leiden University, is handled curtly, even off-handedly, and in Jo’s family’s living room—though in fairness, this is not a novel about Kuyper himself.

The dialogue between Jo and Bram at times seems instructive for the reader rather than natural, and thus contrived, and the presentation of Harry as a near proto-feminist is at times gnawing. If it is true, I’d think a reader would like to have seen more evidence for it. Women’s treatment was, and still is, a genuine concern, and Mrs. Van der Velde drops narrative hints of the need for melioration on this front in nineteenth-century Holland—a baker’s wife serving customers with a suspiciously black eye while her husband yells at her from behind a closed door, and the young, overworked, poorly fed housemaid rescued by Jo.

But the central theme, running like a thread through the novel, is not women’s rights so much as their legitimate gifts, the good involved in discovering them and allowing them to flourish, and, as opportunity serves, the outward-bound use of these gifts that grows from their personal, Spiritled development and exercise. That’s not about leaning in, but looking up, then leaning out. Isn’t that our hope and prayer for all our daughters?

Gerry Wisz is a freelance writer, college instructor, and semi-retired public relations professional who, with his family, is a member of Preakness Valley URC in Wayne, NJ.