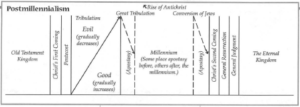

Throughout this series of articles on the major millennial views, I have been stressing the fact that there are two major types of views, each of which has two distinguishable expressions. The first two views considered, classical premillennialism and dispensational premillennialism, share the conviction that Christ’s return will precede the period of the millennial kingdom. Despite their many differences another, related issues, they share this fundamental understanding of the future course of events. Similarly, the view considered in my last article, post-millennialism, and the view to be considered in this article, a-millennialism, share the conviction that Christ’s return will follow the millennium.

However, despite this fundamental similarity between post-millennialism and a-millennialism, there are a number of respects in which these two positions can be distinguished. To complete our survey of millennial views, therefore, we need to consider the view commonly known as a-millennialism. Following the pattern of previous articles, I will begin with a comment on the terminology of “a-millennialism,” and then consider briefly the history and a number of the main features that especially distinguish this view from post-millennialism.

YET ANOTHER COMMENT ABOUT TERMINOLOGY

On more than one previous occasion, I have commented upon some of the terminological confusion that surrounds the subject of the various millennial views. Nowhere does this problem of terminology prove more difficult than in the case of the view commonly known as “a-millennialism.”

Perhaps the most obvious and immediate problem with the term, “a-millennialism,” is that, literally, it means “no millennium.” At first glance, therefore, it would appear that a-millennialism is a position that rejects the idea of the millennium altogether. This would suggest that it is not so much a millennial view at all, as it is a rejection of all forms of millennialism. However, this is not the case, since a-millennialism has a distinctive view of the millennium, as we shall see.

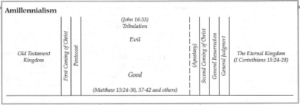

The terminology of “a-millennialism” has been coined, however, because this view rejects the chiliasm of the other major millennia! views. A-millennialism identifies the millennium with the entire period of history between Christ’s first and second coming. Accordingly, it does not look for a golden age millennium either after the return of Christ, as in pre-millennialism, or in the period just prior to the return of Christ. Unlike the traditional chiliasm of post-millennialism, which distinguishes the millennium as a particular period of history prior to the return of Christ but not encompassing the entire era of the New Testament church, a-millennialism regards the present age in its entirety to be the period of the millennium. Because it rejects the idea of a distinguishable millennium or golden age which commences at some point after the early history of the Christian church, this view has been given the name a-millennialism.1

In order to prevent misunderstanding of this view, some have suggested alternative terminology. Jay Adams, for example, in his study of the book of Revelation, The Time is At Hand, has proposed the terminology of “realized millennialism.”2 This terminology reflects the real emphasis of a-millennialism, that the millennium is a present reality, having commenced with the events of Christ’s ascension and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentacost. Still another proposal has been made by Gordon Spykman who, in his Reformation Theology, offers the terminology of “pro-millennialism” as a more appropriate and positive term for this eschatological view.3 It is not a negative view which denies the reality of the millennium, but a positive view which affirms the presence of the millennium here and now before the return of Christ. Of these two proposals, Spykman’s is the more attractive, particularly since it retains a parallelism with the other millennial views, each of which is denominated by a prefixed form of the term “millennialism.” However, terms have a life of their own and it is highly unlikely that any of these or other candidates will displace the traditional language of a-millennialism.

We will continue to speak accordingly, of “a-millennialism,” though in the awareness of its inadequacy and liability to misunderstanding.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF A-MILLENNIALISM

The view which today is known by the terminology of a-millennialism has a long history of advocacy going back to the beginning of the Christian era. Since the fourth and fifth century, it has been the predominant position within the Christian church. Though pre-millennialism has had its advocates throughout the history of the Christian church and has enjoyed a resurgence recently among conservative evangelicals in North America, it is safe to say that a-millennialism has been the consensus position of the largest portion of the Christian church. Louis Berkhof is correct, when he remarks as follows regarding a-millennialism:

Some Pre-millennarians have spoken of A-millennialism as a new view and as one of the most recent novelties, but this is certainly not in accord with the testimony of history. The name is new indeed, but the view to which it is applied is as old as Christianity. It had at least as many advocates as Chiliasm among the Church Fathers of the second and third centuries, supposed to have been the heyday of Chiliasm. It has ever since been the view most widely accepted, is the only view that is either expressed or implied in the great historical Confessions of the Church, and has always been the prevalent view in Reformed circles.4

Though Berkhof does not mention the claim of many present-day post-millennialists that a-millennialism, not post-millennialism, is the relative newcomer, his observations are equally valid in response to this claim.

It is generally agreed that, though the view known today as a-millennialism was already present in the earliest period of the Christian church, the great church Father, Augustine, was instrumental in establishing this view as the predominant one. By treating the millennium of Revelation 20 as a symbolical description of the church’s growth in the present age, Augustine gave impetus to the a-millennialist contention that the millennium does not follow chronologically the early history of the New Testament church. With the exception of some exponents of pre-millennialism, the tenets of a-millennialist teaching prevailed throughout the Middle Ages and during the Reformation. The Reformers were aligned with this broad tradition, though, as we noted in our previous article, there were, soon after the Reformation, advocates of post-millennialism especially within the Reformed tradition.

However strong the influence of post-millennialism may have been within the Reformed churches, especially in North America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the predominant view today is that of a-millennialism. Though there are advocates of post-millennialism among the Reformed churches, and though the majority of conservative evangelicals in North America are premillennialists, the prevailing view among the Reformed churches and the Christian church, broadly conceived, remains that of a-millennialism. It is commonly agreed that, where the historic creeds and confessions address themselves to the subject of the future, they are more congenial to an a-millennialist view than to the other major millennial views. This is true of the Reformed confessions, though they do not explicitly address some of the differences between a-millennialism and post-millermialism.5

THE MAIN FEATURES OF A-MILLENNIALISM

Because there are significant areas of agreement between post-millennialism and a-millennialism, my summary of the main features of a-millennialism will often focus upon those things which distinguish these two views. Just as with the other millennial views, this summary will be very general, recognizing that there are many differences in emphasis and on particular issues among a-millennialists.

The millennium is now perhaps the most important way in which to distinguish a-millennialism from the other millennial views is to note that it teaches the present reality of the millennial kingdom. A-millennialism regards the millennium of Revelation 20 to be a symbolical representation of the present reign of Christ with His saints. During the period of time between Christ’s first advent and His return at the end of the age, Satan has been bound in such a way as no longer to be able to deceive the nations. The millennium, therefore, is not a literal period of one thousand years. The period of one thousand years (ten times ten times ten) represents the complete period within God’s sovereign disposition of history during which He has granted to Christ the authority to receive the nations as His inheritance (compare Psalm 2; Matt. 28:16–20).

A-millennialism is, accordingly, opposed to all forms of “chiliasm,” that is, the teaching that the millennium is a distinguishable period which concludes the period of history between Christ’s first and second coming. This view rejects the idea that at some point in the history of the church the millennial kingdom will be established. Though there are a variety of opinions among a-millennialists as to the nature of the millennium some are more “pessimistic,” others more “optimistic,” as to the triumph of the gospel of Jesus Christ among the nations—a-millennialists do not typically believe that there will ever be a period in history when Christ’s kingdom will prevail upon the earth in the postmillennialist sense. A-millennialists ordinarily reject the post-millennialist conviction that the millennium will be a period marked by universal peace, the pervasive influence and dominion of biblical principles in all aspects of life, and the subjection of the vast majority of the nations and peoples to Christ’s lordship. A-millennialists believe that the Scriptural descriptions of the inter-advental period suggest that the world’s opposition to Christ and the gospel will endure, even becoming more intense as the present period of history draws to a close.

The signs of the times

In the position of a-miliennialism, there is a common understanding that the signs of the times, including in particular the signs of opposition to Christ’s gospel and people (e.g. tribulation, apostasy, the spirit of anti-Christ), are present and future realities. During the entirety of the period between the ascension of Christ and His return at the end of the present age, there will be an on-going conflict, sometimes more intense, sometimes less intense, between the church and the world, the kingdom of God and the kingdom of the evil one. Though there may be in different places or countries and at different times, periods of relative peace and prosperity for the church and people of God, there will never be a time, certainly not a millennial period, in which the cause of Christ will so triumph in the earth that suffering and distress will no longer be experienced by the church of Jesus Christ. This view of the signs of the times regards them as characterizing the history of redemption in the entire period during which Christ is gathering His church by His Spirit and Word. Post-millennialism, by contrast, regards many of these signs to have been (or to be) fulfilled at some point prior to the millennium. It is common, for example, among post-millennialists to regard the signs of the times enumerated in Matthew 24 to refer to the events prior to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 A.D.6 This means that, from the point of view of the millennium, signs of opposition to Christ, like tribulation and apostasy, will no longer characterize history, at least for the duration of the millennium until Satan’s “little season” just prior to Christ’s return at the end of the age.

Revelation 20

Throughout this series of articles on the millennium, the teaching of Revelation 20 has always been close at hand. In the final analysis, the various millennial views can only be tested and justified on biblical grounds, and the key biblical text is, undoubtedly, Revelation 20. Consequently, we will be devoting one or more articles in this series to this key passage. Without settling the exegetical questions here, however, I would like only to summarize the standard view of Revelation 20 among a-millennialists.

Most a-millennialists read Revelation 20 as a passage which, in parallel with several sections of the book of Revelation, describes a vision sequence which covers the entire period from Christ’s first coming to His second coming. Unlike many post-millennialists who read Revelation 19 and Revelation 20 as though they were in chronological succession (Revelation 19 describing the commencement of the millennial period in history, Revelation 20 describing the millennium itself), a-millennialists view the vision of the millennium as a kind of symbolic portrayal of the period of the church’s mission in the world. The binding of Satan described in this vision is a picture of the restraint God has placed upon Satan, preventing him from deceiving the nations, and the certain prospect of the church’s success in discipling the nations.

Though there are differences of opinion among a-millennialists regarding the “first resurrection” and the “coming to life” of the saints who reign with Christ, most a-millennialists understand the first resurrection to be a spiritual one in which all believers participate, particularly the martyred and deceased saints who reign with Christ in heaven. By virtue of this first resurrection, believers are no longer subject to the power of death and have a share in Christ’s reign over all things. Only at the end of the period of Christ’s gathering His church and the reign of His saints will Christ return, the dead be raised, and the resurrection of the body (the second resurrection) occur. The reign of Christ and His saints described in this vision is not a reign of the saints upon the earth, but a reign of the saints who are with Christ in heaven. Thus, Revelation 20 does not describe an earthly millennium, a golden age in the post-millennialist sense, but the history of the progress of Christ’s kingdom upon the earth, as the gospel is preached to the nations, and believers, especially those who are deceased, even martyred for the faith, are given to reign with Christ in the expectation of His triumph at the end of the age.

The Christian’s hope for the future

Another feature of a-millennialism that distinguishes it from post-millennialism is its insistence that the great hope of the Christian and the believer for the future is the return of Christ at the end of the age. Though post-millennialists would regard Christ’s return to be the final, consummating event at the end of this present age, they tend to view history in such a way as to deflect attention from this event to the expectation of a future millennial age. A-millennialists, on the other hand, anticipate that the victory of Christ, and the triumph of the kingdom of Christ, will only occur when Christ returns.

This is a somewhat elusive and difficult point to make. Often times, post-millenniallsts will decry a-millennialists for their pessimism about the prospects of Christ’s kingdom in this present age. A-millennialists, conversely, will scold post-millennialists for being too optimistic and unjustifiably so. A-millennialists are said to be too “other-worldly” in their expectations for the future. Post-millennialists are said to be too “this worldly” in their expectations.

Without attempting to resolve this dispute here, it certainly is true that there is a real difference on this score between these two views. A-millennialism always insists that, in the biblical descriptions of the future, the great and final hope of every Christian focuses upon the event of Christ’s return, His “revelation from heaven” when He will subdue all of His enemies and bring relief to His troubled church (2 Thess. 1). Unlike the expectation of post-millennialism, which teaches a future millennium of one thousand years (or more) of Christ’s reign upon the earth, an expectation which undoubtedly diminishes the urgency and eager anticipation of Christ’s second coming, a-millennialism does not expect any substantial or qualitative change in the circumstance of the church prior to Christ’s return. Indeed, one of the ways in which post-millennialism and a-millennialisrn may be distinguished, is to say that a-millennialism has a more clear expectation of the imminence (the “soonness”) of Christ’s coming again than does post-millennialism. Post-millennialism regards the return of Christ to be a distant reality, one whose fulfillment can only follow upon the millennium or golden age to come.

CONCLUSION

If these main features of a-millennialism are brought together, it is evident that a-millennialism is really a form of post-millennialist teaching absent the “chiliasm” that characterizes classic post-millennialism.7 With post-millennialism, a-millennialism believes that the return of Christ will occur after the millennium. However, against post-millennialism, a-millennialism rejects the notion that Christ’s return will follow a distinct millennial period that comprises only a segment of the period of history between the first and second comings of Christ. A-millennialism, as we have seen, regards the millennium as the equivalent of the entire period of history between Christ’s resurrection and ascension and His coming again. Unlike the expectation of a millennial age, a “golden age” in history before the return of Christ in which the kingdom of God will be realized upon the earth (though falling short of absolute perfection), the a-millennialist expectation is for a continuing history of growth as well as struggle, of advance as well as of temporary retrenchment, for the church of Jesus Christ in this present age. Only at the end of the age, with the return of Christ in glory and power, will every enemy be subdued and Christ’s reign be openly acknowledged in all the earth.

With this summary of the main features of a-millennialism, we have concluded our survey of the four major views of the millennium. No doubt more could be said regarding anyone of these views, and it would be possible to note various differences that exist among their advocates. It has been my intention only to provide a sketch of the most important distinctives of each of the four major millennial views. However, having summarized these four positions, the most difficult task still remains. And that is to evaluate each view by the standard of the Scriptures. To that task, the Lord willing, we will turn in the months to come.

FOOTNOTES

1 Some post-millennialists are fond of calling this view “pessi-millennialism” because it does not teach that the cause of Christ’s kingdom will necessarily triumph and prevail throughout the earth for a lengthy period of many centuries. This language is an example of partisan labeling that does not promote understanding or communication among those who hold differing views, particularly among post-millennialists and a-millennialists.

2 Philadelphia, PA: Presbyterian & Reformed,1970, pp. 7–11. Adams’ position is a kind of amalgam of post-millennialist and a-millennialist views, though it is with the latter that his position is most clearly to be identified.

3 Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1992. pp. 5403–43. It is not difficult to anticipate the objection to this terminology that will come from advocates of the other views: what right does a-millennialism have to the proud title of being “pro-” millennial?

4 Systematic Theology (Grand Rapids, MI Eerdmans, 1941), p. 708.

5 The one exception to this pattern may be the Second Helvetic Confession of 1566 A.D. This confession was first written by Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli’s successor and an influential Reformer in his own right, and later adopted by the Swiss Reformed churches as a confession of their faith. Next to the Heidelberg Catechism, it has been the most popular Reformed confession among the international family of Reformed churches. This confession seems to condemn postmillennialism, when it declares: “We further condemn Jewish dreams that there will be a golden age on earth before the Day of Judgment, and that the pious, having subdued all their godless enemies will possess all the kingdoms of the earth. For evangelical truth in Matt., chs. 24 and 25, and Luke, ch. 18, and apostolic teaching in II Thess., ch. 2,. and II Tim., chs. 3 and 4, present something different” (quoted from Reformed Confessions of the 16th Century, ed. Arthur C. Cochrane [Philadelphia, PA: Westminster, 1966], chap. 11).

6 In my previous articles on the signs of the times, I have already addressed this issue and taken a position that is at odds with this one. Though I did not say so at the time, my view of the signs of the times, if correct. supports an a-millennialist and not a post-millennialist view. We will come back to this issue in a subsequent article.

7 Some readers might wonder why I have not included a certain view of the conversion of “all Israel” as a feature of a-millennialism. Just as many post-millennialists teach the future conversion of the preponderance of the Jewish people, so many a-millennialists reject this teaching and take the reference to “all Israel” in Romans 11:26 to be a reference to all the elect Jews (and perhaps even Gentiles) gathered into the church through the centuries. However, as I noted previously, the advocacy or rejection of this view of the conversion of the Jews is not a sufficient condition for being a post-millennialist or a-millennialist.

Dr. Venema teaches Doctrinal Studies at Mid-America Reformed Seminary in Dyer, IN.