“For I reckon that every phenomenon can be seen, if the sight is sound, hanging by some sort of a navel-string to the Infinite womb.” “The only trouble is that the reverberation dies away so soon in the soul and the bog closes around one again.”1

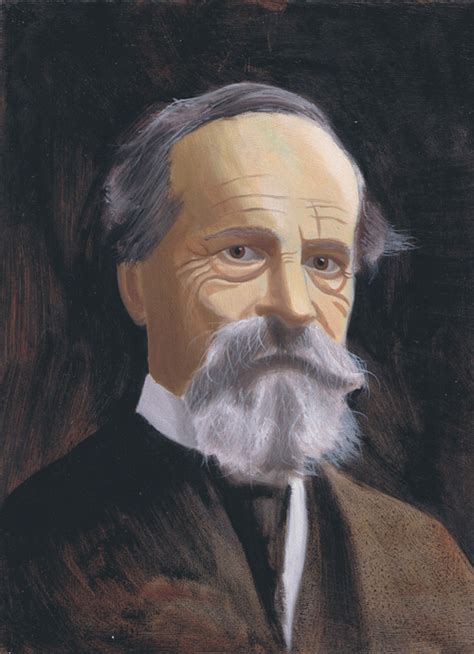

Having been asked to write, from my vantage point as a practitioner and teacher of psychology, a short article on William James—that prophet, king and maverick of American psychology—I cannot but experience both enthusiasm and apprehension as I set myself to attempt to respond to the request.

Enthusiasm: for to encounter James, in biographies, in his philosophical and psychological works, and above all in hi s numerous letters, is an enriching and always eagerly anticipated adventure for me. But to have to try to “place” him somehow, be it in an historical or in a systematic frame of reference, fills me with misgiving, for who shall manage to really catch the mental and spiritual efforts of that many-sided, paradoxical, universal genius by forcing him into a rubric, pigeonhole, a system?

s numerous letters, is an enriching and always eagerly anticipated adventure for me. But to have to try to “place” him somehow, be it in an historical or in a systematic frame of reference, fills me with misgiving, for who shall manage to really catch the mental and spiritual efforts of that many-sided, paradoxical, universal genius by forcing him into a rubric, pigeonhole, a system?

One can of course start by reciting some coldly biographical data: born in 1842 in New York, of Scottish-Irish extraction, good family, religiously learned relatives, many changes of scenery because of travels and studies in many places in the U.S.A. and Europe, wavering in vocational ambitions,painting?, chemistry?, biology?, medicine?, philosophy?, psychology—he studied them all—author of a colossal introduction to the principles of psychology, later of more strictly philosophical works, professor of psychology and philosophy at Harvard University, friend of many great minds in the fields of science, letters and philosophy, called the “psychological pope of the new world” by a European writer2 while a scandalized American colleague thought James had written too much “…with all the delightful insouciance, the naive egoism, of a boy.”3

But what do such little facts convey as regards the man: James, and his view of man? Nothing much, really. Could we not find in his activities as a scholar and teacher some characteristics of the man, so as to have a grasp? Well—let us see…

Does William James initiate academic experimental psychology in the U.S.A.? Indeed: in 1876 or thereabouts he had two little rooms in Harvard College furnished with some apparatuses to give demonstrations and do experiments of a psycho-physiological nature. He regarded an experimental, physiological psychology (studying the physiological processes in perception in their relations to mental experience) to be of essential importance in any psychology. He wrote about this already in 1868 to his friend Tom Ward:

“It seems to me that perhaps the time has come for psychology to be a science—some measurements have already been made in the region lying between the physical changes in the nerves and the appearance of consciousness—at (in the shape of sense-perceptions), and more may come of it. I am going on to study what is already known, and perhaps may be able to do some work at it.”4

After he had established some experimental facilities at Harvard, he induced one of the most promising experimentalists he knew, the German Hugo Munsterberg, to accept an appointment at Harvard. James, it appears, was deeply convinced of the need for an experimental approach in psychology. It is somewhat disconcerting, then, to discover that he did not like it at all: “…the thought of psycho-physical experimentation, and altogether of brass-instrument and algebraic-formula psychology fills me with horror.”5

There are those who believe that James was basically something of an existential philosopher. The Dutchman J. Linschoten has written a quite impressive study attempting to prove it.s On the other hand, James is customarily viewed as a founder of the American philosophy of pragmatism; after all, he introduced the word as a name for his entire world-and-life view (—to the dismay of his teacher Peirce, who coined the word as a label for his view of logic and human reasoning). In this context James is seen as an important forerunner of Behaviorism, the American school of psychology, which emphasizes the study of animal and human behavior from the standpoint of a strict determinism and natural evolution. And certainly James was a determinist: “I’m swamped in an empirical philosophy—I feel that we are nature through and through, that we are wholly conditioned, that not a wiggle of our will happens save as the result of physical laws,…”7

But then American behavioristic psychology actually came about, in the years around World War I, and stressed the necessity to see psychology as an extension of biology, to “explain” all of man in terms of biological functions no different in principle than those in animals. The founder and leader of the movement, John B. Watson, repudiated James completely for he saw James as an unscientific metaphysician! As for James’ reaction to Behaviorism: he died before Watson, in 1912, wrote his epoch-making “Psychology as the behaviorist views it.” But one can guess what James would have felt if he had been able to see to what extent a crass materialism permeated American psychology in the decades after his death, when we read that in a lecture he stated:

“Many persons nowadays seem to think that any conclusion must be very scientific if the arguments in favor of it are all derived from twitching of frogs’ legs—especially if the frogs are decapitated—and that, on the other ,hand, any doctrine chiefly vouched for by the feelings of human beings—with heads on their shoulders—must be benighted and superstitious.” “With these persons it is forever Science against Philosophy, Science against Metaphysics, Science against Religion, Science against Poetry, Science against Sentiment, Science against all that makes life worth living.”8

No—James certainly would not have been a Behaviorist!

This becomes even more obvious when we discover that James was intensely interested in that most suspect of “unscientific” fields: the study of so-called “occult” phenomena, or as it is called today: “Para-psychology.” He was one of the founders of a national society for the study of such mysterious phenomena as mind-reading, haunted houses, second-sight, magic healing, etc. To be sure, he was quite skeptical about many sensational stories and fantastic theories. He believed that “…the more we can steer clear of theories at first, the better. Facts are what are wanted.”9 At the same time, however, James was not one of those who summarily dismissed the whole problem as nonsense. As a matter of fact, in his more unguarded moments James confessed to be convinced of some reality to the “supernatural” phenomena. He was in some ways even akin to the Swiss psychiatrist

C. C. Jung who would later develop a curiously speculative theory about a kind of super-mind, existing independent of all individual human minds, expressing itself in various ways through the individual persons, in dreams, fantasies, visions, and parapsychological phenomena. James wrote that he was convinced that: “…there is a continuum of cosmic consciousness, against which our individuality builds but accidental fences, and into which our several minds plunge as into a mother-sea or reservoir.”10

Many more paradoxical viewpoints and attitudes of William James, both in psychology and philosophy, could be related. His ideas on human emotions, knowledge, morality, religion, were never a nicely consistent and logical unity. His first and perhaps still most important work, Principles of Psychology, is a good example: very loosely organized, a multitude of observations and seemingly contradictory comments, brilliantly written, intensely personal and yet almost indecently learned and scholarly, obviously the work of a great mind and yet scandaliZing many colleagues, whose reactions were varied but perhaps best summarized in the words of one wry commentator who said : “A good book, but too lively to make a good corpse and every scientific book ought to be a corpse.”11 It took James twelve years to write the book (he had originally expected that it would be two years…) and when it finally appeared, in 1892, he was not entirely satisfied with it, it seems, for he called it “…a loathsome, distended, tumefied, bloated, dropsical mass, testifying to nothing but two facts: lst, that there is no such thing as a science of psychology, and 2nd, that W. J. is an incapable.”12 His opinion did not keep the book from becoming a best-seller and a classic, even today—something few other introductory texts written more than a half century ago can lay claim to!

Another very interesting and now just as “classic” a book developed out of a number of lectures: the famous Varieties of Religious Experience. In this James attempts to come to grips with the problems of the meeting of religion and science. Here again we can find little “system” in the presentation and logical analysis of the various topics. Again we are confronted with the peculiar genius of James, who could not write or think a single sentence purely in the abstract, but always was fully involved, as a person, in whatever he did in the field of learning.

All in all, as were his works, so was James:

“…unsystematic—exploring and depicting human nature in all its dimensions, gathering facts from any quarter and by any method, and theorizing as the spirit moved, undismayed by the prospect of starting something that could not be completed.”13

One can not find a worked-through “system” in James; he can not be “located” or “classified”; he was and is too many things to too many in too many ways to be pinned down. And certainly when one only tries to analyze the expressed thoughts of James, one does not do justice to the man. Not even an attempt to see beyond what he said in order to grasp what he meant can be enough, it seems to me. In a way, James cannot really be “discussed” or “analyzed”; one has almost to “experience” him, to sense what it was he was trying to express in all his works and letters. Since he had no set “system” he had no “school” and no real “pupils.” People with widely varying and contrasting theories can and do find inspiration, challenge and fortification in James. His influence on contemporary psychology and philosophy is immense and yet quite vague and undefinable. Everybody in American psychology will agree that James was a great man, perhaps the greatest so far in U.S.A. psychology. But nobody really knows what to make of James in the setting of contemporary research.

It occurs to me that when one wants to “understand” James, one has to look, not first of all for the words he in philosophy or psychology books, but for the personal experience which went into what James said and wrote. And that experience, throughout James’ life, was the anxiety inherent in the recognition of man’s paradoxical, dual nature. Of this R. Niebuhr, the theologian. was to say: “…man. being both bound and free, both limited and limitless, is anxious. Anxiety is the inevitable concomitant of the paradox of freedom and finiteness in which man is involved.”14 All his life James encountered this paradox of freedom and determinism, and he saw it in every act and aspect of man. It was not only an abstract, rational conclusion for him, but a very intense, personal experience also, to the extent of causing mental depression and hypochondria in him for several years, so much so that for a time it appeared that James would not be able to lead any kind of professional life. This experience was also profoundly religious and James never fell prey to the temptation of “explaining” religious feelings as “merely” the products of social and psychological factors which could be scientifically analyzed. The following passage, relating the emotions of a man confronted with the “abyss” of human nature, is illustrative of the intensity with which James felt, thought and worked.

James has never resolved the paradox; he let it stand. He saw it expressed in all man’s being; not as a kind of summation: certain aspects of man are determined by nature, while in other aspects man is free and responsible. This is not what James found; he was struck by the paradox as operative throughout man’s being.

“I feel that we are nature through and through, that we are wholly conditioned, that not a wiggle of our will happens save as the result of physical laws, and yet notwithstanding we are en rapport with reason. How to conceive it? Who knows?…It is not that we are all nature but some point which is reason, but that all is nature and all is reason too.”16

When James says “reason” he means something akin to “transcendence,” that which makes man reach out beyond mere nature.

To characterize James as a “pragmatist” is not wrong. He did defend the position that what counts in life is what man does with it, what function it has in man’s existence, how he lives with it and by it. This emphasis on “pragma” or “deed,” “action,” is certainly native to James’ philosophy and to the American philosophers after him, such as John Dewey, Rowland Angell, etc.

But the word “pragmatist” is a poorly pale label indeed to characterize that striving for insight, completeness of understanding and respect for man’s true nature, which so passionately guided William James in his learnings and teachings. A man of profound sensitivity to the subtleties of human experience, as well as a brilliant intellect, he was always willing to accept the facts of experience, even if they conflicted with the ambitious theories of the sciences of his day. If anyone, then William James is a prime example of the power of common grace to save a glimmer or even a great sparkle of intuition, also in those who cannot bring themselves to accept the personal revelation of the Personal God. Both the richness and the tragedy of James’ profound perception of reality, a perception from which the Christian can learn much with deep gratitude, is apparent in the quotation which I selected as a motto for this article. Whatever aspects of reality James observes—he senses that it points, somehow, to the great Originator, who is the only source of meaning in the universe. Yet the heavy load of unbelief continuously weighs down upon his efforts to trace the meaning and foundation of things. And thus the paradox stands, as the final “…and yet…” which remains the ultimate of insight the secular mind can attain.

References:

1. From a letter to Tom Ward, written in Dresden, May 24, 1868. Quoted in R. B. Perry, The Thought and Character of William James, Vol. I, Little, Brown and Co., Boston, 1935, p. 277.

2. See R. B. Perry, op. cit., Vol. ll, p. 145.

3. Ibid., p. 104.

4. W. James., The Letters of William lames, Vol. I, Longmans, Green and Co., London, 1920, pp. 118–119.

5. See R. B. Perry, op. cit., Vol. II , p.195.

6. J. Linschoten, Op weg naar een fenomenologische psychalogie, Biileveld, Utreeht, 1959.

7. R. D. Perry, op. cit., Vol. I, p. 472.

8. Ibid., Vol. II, pp. 30–31.

9. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 160.

10. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 172.

11. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 104.

12. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 48.

13. Ibid., Vol. II, p. 91.

14. R. Neibuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man, New York, 1941, p. 182.

15. W. ]ames, The Varieties of Religious Experience, Mentor book paperback, 1958, p. 135. James writes as if the experience were someone else’s but later confessed it was his own experience.

16. R. B. Perry, op. cit., Vol. I, pp. 472–473.

Few men have had greater influence on the American mind and yet remain so difficult to assess accurately as William James. Dr. Roelof J. Bijkerk, associate pastor of Psychology at Calvin College, Grand Rapids, MI, leads us to the heart of the problem—the inability of James on his own basic assumption to unravel the riddle of man as both bound and free.