The year 1963 marks the four hundredth anniversary of the publication of the Heidelberg Catechism. This precious document, one of the creeds of a number of Reformed denominations, in this country and abroad, has enjoyed singular popularity among Reformed people ever since Its first appearance. It has been translated into many languages and is still taught and preached regularly in many churches which hold to the Reformed faith.

It is called the Heidelberg Catechism because it was composed at Heidelberg, Germany, the capital of the German Electorate of the Palatinate, at the behest of the Elector, Frederick II. He wanted the Reformed. instead of the Lutheran, faith to be the dominant religion in his domain and charged two young theologians, Zacharias Ursinus and Caspar Olevianus, with the task of writing a catechism as an instruction book for the youth of the church. Though the product of their pen is a book on doctrine, its practical approach and heart-warming spirit has endeared it to the hearts of untold numbers of Christian people. Many Reformed denomination still require its exposition in public worship service.

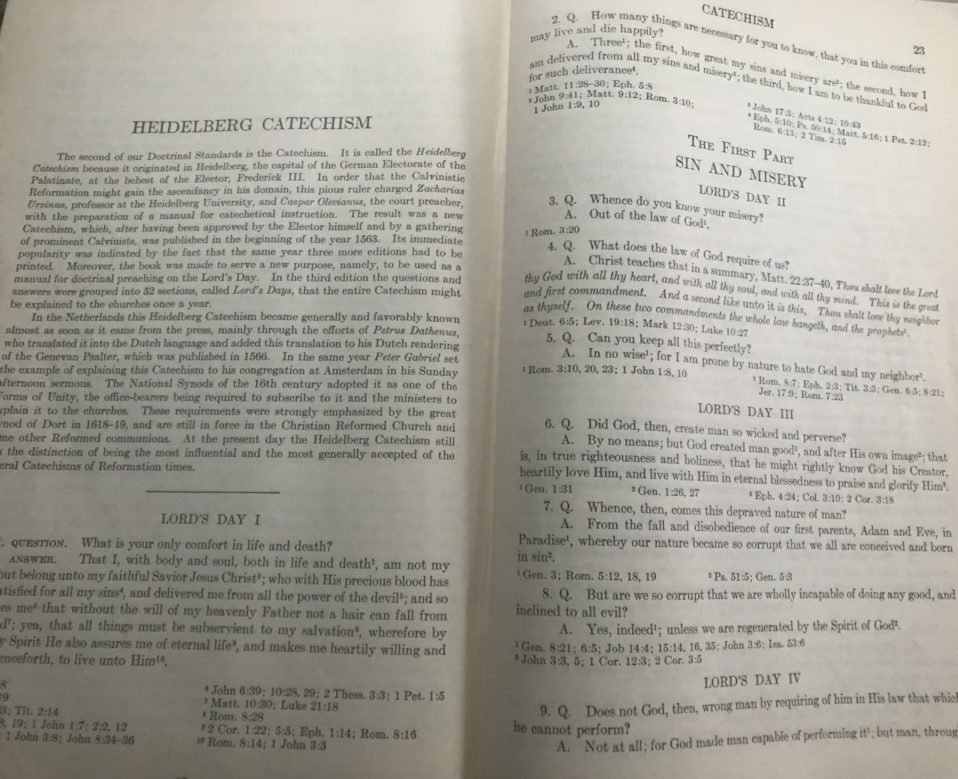

Those in charge of this paper were impelled to set aside space in three of our 1963 issues for as many articles on timely subjects that deal with the Heidelberg Catechism. The fifty-two Lord’s Days of this booklet constitute one of the creeds of all churches of Reformed persuasion. It “has the distinction of being the most influential and the most generally accepted of the several Catechisms of Reformed times.”

Dear reader, do not take for granted that you know all about the answers given to the questions asked in this Catechism. We suggest that you read it through, quietly and thoughtfully, during the next few weeks. You will discover spiritual riches of truth which you have not see before. H.J.K.

In the Reformation period many Protestant Catechisms and Confessions of Faith were produced. Most of them are theological masterpieces, but not all have achieved popularity. One of the most popular is the Heidelberg Catechism. The aim of this article is to point out a few of the features which have in the past rendered that Catechism precious to numerous believers and may well render it precious to believers today.

A COMPREHENSIVE CATECHISM

The Heidelberg Catechism consists of 129 questions and answers. All the questions excel in brevity and so do most of the answers. In the Psalter Hymnal of the Christian Reformed Church the whole covers only 21 pages. And yet it is a tru1y comprehensive—although, of course, not an exhaustive—statement of the Christian faith.

Its three parts: Misery, Deliverance, and Gratitude, or, to employ a bit of alliteration, Sin, Salvation, and Service, describe the entire pilgrimage of the child of God from Mount Sinai to Mount Calvary and from Mount Calvary to Mount Zion.

Worthy of special note is the fact that the Heidelberg Catechism, although 400 years old, gives a strikingly adequate answer for this day and age to the question just what Christianity is. Again and again one hears the cliche repeated that Christianity is not doctrine but conduct. The truth of the matter is that it is doctrine as well as conduct, that, prior to both of these, it is history, and that, in addition, it is worship. All four of those aspects of Christianity are stressed in the Catechism under consideration.

The creation of the universe as related in the first chapter of Genesis, the fall of man as related in the third chapter, the deluge in the days of Noah, the virgin birth of Jesus as attested by Matthew and Luke, his bodily resurrection as affirmed by all four of the evangelists, and his ascension into heaven as most fully described in the Book of Acts are today assigned by men with a reputation for scholarship to the limbo of mythology or the supra-historical or Geschichle in distinction from Historie. The Heidelberg Catechism does nothing of the kind. It regards all of them as history in the most ordinary and generally accepted sense of that term. And well may it, for such historical events constitute the very foundation of the Christian religion. Small wonder that most of them are enumerated in that ecumenical Confession of Christendom known as the Apostles’ Creed. If the foundation is destroyed, the whole structure will topple into ruins. Did not the Apostle Paul declare: “If Christ be not risen, then is our preaching vain, and your faith is also vain” (I Cor. 15:14)? Christ’s resurrection is one of several historical events with which Christianity stands or falls.

That Christianity ·is doctrine is plain as broad daylight. To name a few of the most cardinal doctrines of Christianity, it is the doctrine of the divine inspiration and consequent inerrancy of Holy Scripture, the doctrine of the Holy Trinity, the doctrine of the two natures of Christ, the doctrine of the deity and personality of the Holy Spirit, the doctrine of regeneration, the doctrine of substitutionary atonement, the doctrine of justification by faith only, the doctrine of divine providence, the doctrine of adoption, the doctrine of the holy and universal church, the doctrine of everlasting punishment. All these doctrines to man of which great violence is being done today by men occupying high places in the Christian church, are taught in the Heidelberg Catechism as essential to Christianity.

Those who stress Christian doctrine are often accused of belittling and even neglecting Christian conduct. That charge cannot be laid at the door of the Heidelberg Catechism. Of it 52 Lord’s Days not fewer than 21 are devoted to the subject of the Christian life of gratitude. And, with the exception of the first and the last commandments, an entire Lord’s Day is devoted to each of the ten commandments of the moral law. Answer 114 says of believers that “with earnest purpose they begin to live, not only according to some but according to all the commandments of God.”

In a sense the Christian is a mystic. In other words mysticism of a kind is of the essence of Christianity. It consists in communion with God regulated by the Word of God and mediated by the Spirit of God. It comes to vivid expression in prayer. Also that aspect of Christianity is strongly emphasized in the Heidelberg Catechism. The last eight Lord’s Days are devoted to a study of prayer, the Lord’s Prayer in particular.

A CONSTRUCTIVE CATECHISM

The Heidelberg Catechism is emphatically controversial. In view of the time of its production and the occasion for its promulgation that could hardly be otherwise. Romish error exposed. In the days of the Reformation that was absolutely necessary. And, inasmuch, as significant differences on certain points of doctrine had arisen within Protestantism, Ursinus and Olevianus, the authors of the Catechism, found it fitting to refute Lutheran and anabaptist aberrations also.

Attacks on Roman Catholic heresy are numerous in the Catechism. A few examples may well be cited. Question 30 asks: “Do such, then, believe in the Savior Jesus who seek salvation and welfare of saints, of themselves, or anywhere else?” The emphatic answer reads: “They do not; for though they boast of him in words, yet in deeds they deny the only Savior Jesus; for one of two things must be true: either Jesus is not a complete Savior, or they who by a true faith receive this Savior must find in him all things necessary to their salvation.” Answer 61 declares uncompromisingly that justification is by faith alone. It says: “Not that I acceptable to God on account of the worthiness of my faith, but because only the satisfaction, righteousness, and holiness of Christ is my righteousness before God, and I can receive the same and make it my own in no other way than by faith only.” Answer 80 avers militantly: “The mass teaches that the living and the dead have not the forgiveness of sins through the sufferings of Christ unless Christ is still daily offered for them by the priests; and that Christ is bodily present under the form of bread and wine and is therefore to be worshipped in them. And thus the mass, at bottom, is nothing else than a denial of the one sacrifice and passion of Jesus Christ, and an accursed idolatry.”

Perhaps the most serious difference in the Reformation period between Lutheranism and the Reformed faith concerned the human nature of Christ. Lutheranism taught that Christ’s divine nature, having interpenetrated his human nature, had communicated to it the attribute of ubiquity or omnipresence and that consequently the very body and blood of Christ are present in, with, and under the sacramental elements of bread and wine. Lord’s Day XVIU insists that, although the two natures of Christ are never separated from each other, his human nature “is no more on earth.” Also, in explaining the second commandment of the decalogue, Lord’s Day XXXV condemns the Lutheran use of images in the churches “as books for the laity.” Question and Answer 74 uphold in opposition to Anabaptism the practice of infant baptism.

Today there is in most Protestant churches a strong aversion to doctrinal controversy. In view of the undeniable fact that grave errors abound both within the church and in the so-called cults or sects, that is an alarming situation. Such was not the case in the Reformation era. Then the truth was dearer to a believer than his possessions, even his wife and children, yes, his own life. He was wont to sing:

“Let goods and kindred go, This mortal life also; The body they may kill, God’s truth abideth still.”

Present-day disgust with doctrinal controversy is due in large measure to indifference to God’s truth. He who is profoundly concerned about the truth, as every Christian must be, cannot but we1come its vigorous defense.

Every once in a while one hears a sharp distinction made between controversial preaching and teaching on the one hand and constructive preaching and teaching on the other. The latter is wont to be extolled, the former condemned. So far as the Heidelberg Catechism is concerned that antithesis is false. The Catechism does indeed refute error, and it docs so in no uncertain terms, but it does not stop there. Rather, it sets forth the truth over against error. Thus its emphasis becomes decidedly positive. And how obvious it is that, just as white never stands out as clearly and boldly as when it is placed against a black background, so the truth never stands out as clearly and boldly as when it is contrasted with error. Controversial presentation truth can be highly constructive. Of that fact the Heidelberg Catechism offers convincing proof.

A CONFESSIONAL CATECHISM

A distinction is sometimes made between a Catechism and a Confession. But a Catechism can very well be a Confession. The Heidelberg Catechism is. It is a Confession in the form of questions and answers.

Let no one think that the Heidelberg Catechism is an objective or abstract statement of Christian doctrine such as one expects to find in a textbook of Dogmatics.

Nor may this Catechism be conceived of merely as a document in which a church confesscs its faith. To be sure, it is that too. Many Reformed churches have officially adopted it as a doctrinal standard.

The Heidelberg Catechism is confessional in a much more specific sense. It is a confession of personal faith by the individual Christian.

How evident that becomes at the very outset! The Christian confesses “that I with body and soul, both in life and death, am not my own, but belong unto my faithful Savior Jesus Christ; who with his precious blood has fully satisfied for all my sins, and delivered me from all the power of the devil; and so preserves me that without the will of my heavenly Father not a hair can fall from my head; yea, that all things must be subservient to my salvation, wherefore by His Holy Spirit he also assures me of eternal life, and makes me heartily willing and ready, henceforth to Jive unto him.” And when defining true faith in Answer 21, he says: “true faith is not only a sure knowledge whereby I hold for truth all that God has revealed to us in his Word, but also a firm confidence which the Holy Spirit works in my heart by the gospel, that not only to others, but to me also, remission of sins, everlasting righteousness and salvation are freely given by God, merely of grace, only for the sake of Christ’s merits.” That intensely personal note pervades the whole of this Catechism.

No doubt, the feature under discussion has contributed immeasurably to the preciousness of the Heidelberg Catechism to countless children of God. It is a confession that wells up from the very bottom of their believing, hoping, and loving hearts. As they peruse the Catechism, their souls respond time and again with a fervent “Amen.” Their inmost being is strangely warmed. They exclaim, “My Lord and my God!”

In consequence this Catechism is a powerful antidote for orthodoxism or dead orthodoxy, which may be defined as a cold, intellectual acceptance of the truths of Holy Writ without a preceding change of heart and without a subsequent and consequent change of life. Popularly put, the emphasis throughout is not merely on head-knowledge, necessary though that is for salvation, but on heart-knowledge, which is eternal life itself, according to the words of the Lord Jesus: “This is life eternal, that they might know thee, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom thou hast sent” (John 17:3).

A GOD-CENTERED CATECHISM

It has sometimes been intimated that the Heidelberg Catechism, although essentially a Reformed Confession and admittedly a doctrinal standard of many Reformed churches, is hardly emphatically Reformed. Particularly in the light of its opening question it has been said to put more emphasis on man’s comfort and less emphasis on God’s glory than one might reasonably expect of a formed Confession.

True it is that not each of the so-called five points of Calvinism looms as large in the Heidelberg Catechism as it does in the Canon of Dort, but that, of course, is because Arminianism had not yet reared its ugly head. As a matter of plain fact, the Catechism is God-centered. And is not God-centeredness the hallmark of the Reformed theology?

The first question together with its answer does indeed deal with the believer’s comfort, but that comfort is said to consist in his not being his own but being the very property of another, that other being Jesus Christ, who is his divine Lord as well as his Savior.

As for Sin, knowledge of it is said to be out of the law of God, the great and first commandment of which demands love for God with one’s entire being (Questions and Answers 3, 4).

As for Salvation, from its inception to its completion it is said to belong to the Triune God, and to him alone. God the Father provided the Mediator. From God he was made unto us wisdom, righteousness, sanctification, and complete redemption (Question and Answer 18). The church consists of God’s elect (Answer 54). God the Son merited salvation to the full so that all human merit is ruled out once and for all (Lord’s Day XXIII). God the Holy Spirit applied salvation by imparting to the spiritually dead sinner the new birth, and as the author of faith the same Spirit makes the sinner a partaker of Christ (Answer 8, 53). Thus the Catechism ascribes to God precisely all the glory for man’s salvation. In the process of his salvation man is completely passive at the beginning, and when he subsequently becomes active he does so solely by the grace of God.

As for Service, it is to be motivated by gratitude to God for his great salvation (Answer 86) and expressed in good works, “which are done according to the law of God and to his glory, and not such as are based on our own opinion or the precepts of men” (Answer 91).

The Catechism explains at length the Apostles’ Creed, the Decalogue, and the Lord’s Prayer. Each of these is emphatically God-centered. The Apostles’ Creed consists of three parts: God the Father and our creation, God the Son and our redemption, God the Holy Spirit and our sanctification. The Decalogue is the law of God and an expression of God’s very nature. In it God commands what he commands because he is who he is. It requires love for God above all else and love for neighbors for God’s sake. Of the six petitions in the Lord’s Prayer the first three concern God’s name, God’s kingdom, and God’s will and it ends with doxology ascribing to God the kingdom, the power, and the glory for ever.

The Heidelberg Catechism in its entirety is God-centered. That feature can only endear it to every true child of God who makes its acquaintance. For his deepest drive is love for God and his highest aim the glory of God.