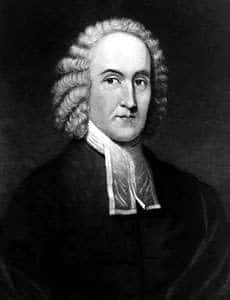

Three hundred years ago this month (October 5), Jonathan Edwards greeted the world in East Windsor, Connecticut. He was the lone son of Rev. Timothy Edwards and his wife, Esther Stoddard Edwards. But Jonathan was not the sole child—he had ten sisters. This auspicious year (1703) was also the year of John Wesley’s birth. The great American Calvinist and the great British Arminian would share natal years, but their soteriology would be as distant as the span of the Atlantic Ocean (and beyond).

To Yale

Edwards was precocious. By age seven, he had learned Latin (from the ‘home school’ tutelage of his father). By 1716, at age twelve, he had added Greek and Hebrew to his vocabulary. In that twelfth year, he matriculated at the Collegiate School of Connecticut (later Yale College, now Yale University) in the branch campus at Wethersfield, Connecticut.

Three years later, Edwards moved to New Haven for his senior year. He graduated first in his class with his Bachelor’s degree at age sixteen (1720). After two more years at Yale (1720–22) in which he labored on his Masters degree, Jonathan Edwards received a call to a Presbyterian Church in New York City (a branch congregation of the First Presbyterian Church of that locale). The small fledgling congregation was destined to fail from financial problems and Edwards was back in Connecticut in April 1723 after a nine month ‘pastorate’. Returning to his Masters studies, he completed the requisite thesis in September 1723. It was entitled “A Sinner is Not Justified before God except through the Righteousness of Christ obtained by Faith”.

To Northampton

A short ‘pastoral’ sojourn in Bolton, Connecticut (November 1723–Spring 1724) ended when he was invited to serve as Tutor at Yale (1724–26). In August 1726, his maternal grandfather, Solomon Stoddard, invited Jonathan to assist him in the church at Northampton, Massachusetts. Solomon Stoddard, the ‘Pope’ of the Connecticut Valley, had labored in Northampton for 55 years. Stoddard’s peculiar view of the Lord’s Table was to be portentous: he invited non-communicant persons to the Table in the hope that they would be converted by means of the experience. In 1726, Jonathan little realized the ominous significance of his grandfather’s ‘converting ordinance’ view of the Lord’s Supper.

Edwards was ordained to the ministry February 15, 1727 and served with his grandfather until the latter’s death February 11, 1729. Meantime, he married Sarah, a seventeen year-old member of the wealthy Pierrepont family in New Haven. Edwards was 23 years old at the time, but confessed that he had been smitten with Sarah when she was 13.

The union between them was to produce eleven children. Relief from the duties of parenting was found by Jonathan and Sarah in delightful afternoon horseback rides in which Jonathan would discuss the profoundly penetrating ruminations of his amazing mind with his best beloved. Associating each thought with a piece of paper pinned to his great coat, Sarah would help him arrange and record the thoughts on their return to the parsonage.

From 1729, Edwards was alone in the shoes of the ‘Pope’ of Northampton. Preaching was his work; it was his meat and drink. For 13 hours per day (according to his first biographer, Samuel Hopkins), Edwards labored over his sermons in his study. The heart of his work was the justification of God in his mercy—and his wrath. And this drove Jonathan Edwards to Jesus Christ. The Son of the Father is the chief affection of the believer—an affection generated by the breath of the Holy Spirit. One of the favorite terms for the person and work of Christ on the Edwards tongue (and pen) was the word “sweet”. Christ Jesus was the sweetest Savior; his grace was the sweetest favor; his presence was the sweetest savor.

To Boston

Edwards was not to be destined to revel in Christ’s sweetness without the furnace of controversy. The hostility began when he was asked to deliver the ‘Great and Thursday Lecture’ on July 8, 1731. All Boston turned out to hear the ‘Pope’s’ grandson address them on the topic “God Glorified in the Work of Redemption by the Greatness of Man’s Dependence upon Him, in the whole of it.” It was a straightforward declaration of sola gratia.

Boston objected. Boston in 1731 had already subtly embraced Arminianism and worse, Latitudinarianism and Deism. As Edwards exalted classic Reformed doctrines of free grace, man’s native depravity, the sinner’s dependence on God alone—yea Christ alone—for salvation, Boston’s elite winced and cringed. Edwards was too old-fashioned for their progressive lights. The young grandson of Solomon Stoddard would most definitely not be invited back!

Revival

Two years after he had caused a stir in Boston, the Holy Spirit began to stir the hearts in his own hometown and congregation. While Edwards rebuked the young people of his church for their Sabbath evening ‘frolics’ (drinking bouts, lewd songs and language, general Sabbath desecration), he also invited them to his home/parsonage to meet with him and discuss “the things of the Lord.” The young people agreed, suspended their ‘frolics’ and turned to Bible study and discussion with their pastor on Sabbath evenings. It was the beginning of the “surprising conversions”.

The following year (1734), Edwards launched a series of sermons on justification by faith. Within a year, the Northampton revival was at its peak. Edwards himself was surprised and catalogued the revolution at Northampton in the Faithful Narrative of Surprising Conversions (1737). John Wesley was to read Edwards’ book the year after its publication as he walked from London to Oxford. He wrote, “This is the Lord’s doing and it is marvelous in our eyes.“

Back in Massachusetts, the Northampton church had returned to ‘normal’ by 1736. One factor in the decline in fervor was the suicide of Edwards’ uncle (Joseph Hawley) who imagined that a voice had commanded him to slit his throat. Hawley had suffered from extreme depression, but his death depressed the revival in the village.

The Great Awakening

Four years later, the Grand Itinerant, George Whitefield, arrived in Northampton at the height of the Great Awakening. Edwards invited Whitefield to spend four days in the Edwards home. When Whitefield preached on the Lord’s day, Jonathan Edwards sat before him in tears. Whitefield’s preaching was sweet, too!

It was during the Awakening in July 1741 that Edwards delivered the most famous sermon in American history: “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God.” Most of us have been exposed to Edwards via this message. For power and imagery, it is probably unsurpassed.

Yale Commencement

In the fall of 1741, Edwards was invited to deliver the commencement address at Yale, his alma mater. The address formed the basis of his book Distinguishing Marks of a Work of the True Spirit of God (1741). In that speech and work, Edwards was defending the Great Awakening against its critics. Yes, there were excesses in the Awakening—especially the ‘falling down fits,’ ‘swoons’ and the noisy outcries heard in many venues. But Edwards cautioned that the critics not throw the baby out with the bathwater. Excesses did not negate the genuine work of the Holy Spirit. That work was a sincere love for God Himself—Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Edwards emphasized that bodily effects were not a true mark of the work of the Holy Spirit. The true work was the regenerating act of the Holy Spirit on the heart—a work evidenced in love for Christ. In his follow-up book, Charity and its Fruits (an exposition of 1 Corinthians 13), Edwards directed his readers to Paul’s central affection—love for Jesus Christ. Love of one’s personal religious experience was emotionalism, fanaticism, subjectivism because it was anthropocentric (me-centered because man-centered). But love for Christ was other-oriented, theocentric and Christocentric passion. Such affection for Jesus looked away from self to the Savior. In accordance with the apostle’s emphasis (Distinguishing Marks was an exposition of 1 John 4), Edwards urged his hearers/readers to turn from self-love to God-in-Christ-by-the-Holy-Spirit love.

Bad Book Incident

Back in Northampton, normalcy had begun to brew hostility to the village pastor. In 1744, squabbles erupted over Edwards’s salary (it was withheld by the church); over Sarah’s clothing and jewelry (she was “vain”). But the lid blew off when the village boys got hold of a book on midwifery. The boys began to taunt the village girls as “nasty creatures”—even teased them in public about their menstrual periods.

To Jonathan Edwards, this was public lewdness as well as disrespect for the way God had created the female of the species. At the close of a worship service, Edwards read a list of persons who were summoned to appear before the elders. But in reading the names, Edwards did not distinguish between the accused and those being summoned merely as witnesses. All Northampton broke out in an uproar. While three boys were disciplined by the church as a result (and they declared their contempt for the authority of the elders in language which would outrage even us in this profane era!), the damage to Edwards’ pastorate was irreversible.

For four years (1744–48), Edwards was the object of bickering and backbiting. Most of it arose from the town merchants, who resented Edwards’ authority and counsel, i.e., that the Bible and the preached Word are the rule of life in the community of the saints—even when the saints do “business”. Moneyed interests in Christendom face the same dilemma even now. Will they use their God-given wealth to serve the Lord Jesus; or will their money be the club which they hold over the humble servants of Christ? Every wealthy Christian should beware of riches (as Christ and the entire New Testament warns them). For wealth used against God’s true and humble servants is the tool of the Devil.

Break with his Grandfather

The last straw was a flashback to Edwards’ grandfather and the Lord’s Supper. Jonathan came to believe that Scripture did not present the Lord’s Supper as a converting ordinance. When he published his views (An Humble Inquiry into the Rules of the Word of God concerning the Qualifications Requisite to a complete standing and Full Communion in the Visible Christian Church [1749]), his detractors accused him of demanding assurance of salvation for admission to the Table.

Edwards required a credible profession of faith for admission to the Lord’s Supper (i.e., a knowledge of the basic teaching of the Christian faith; a profession of acceptance of that doctrine; a life which reflected that profession).

While this may seem like a ‘no brainer’ to us, we must remember that Stoddard’s position allowed people at the Table who had made no profession of faith at all. Hence Edwards’s change of mind was a rejection of his sainted relative and a bar to social acceptance in the community. Such a shift was unforgivable.

To Stockbridge

On June 22, 1750, Edwards was overwhelmingly dismissed from his pulpit (the vote was 200 to 20, a margin of 10 to 1 against him). Ironically, he was asked to remain and supply the pulpit for over a year after his dismissal.

Unemployed, Edwards, his wife and ten children left Northampton in November 1751. The family made their way west to an Indian village and frontier stockade at Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Here Jonathan Edwards, erudite, profound, powerful preacher, proclaimed the riches of the gospel to the Mahican/Mohican and Mohawk Indians. How did the great theologian communicate with the (mostly) illiterate Native Americans? Very plainly and very patiently. Here is a sample outline of a sermon on Hebrews 11:14–16 preached to the aboriginal Americans: (1) This world is an evil country; (2) Heaven is a better country. Gracious simplicity from a theological genius!

The Stockbridge years gave Edwards peace—peace and time to write. His greatest works date from these years of relative quiet in which he put down on paper books which had been rumbling about in his mind (and jotted down in his notebooks) for years. The magnificent Freedom of the Will (1754) which, once understood, makes Arminianism an impossibility; indeed impossible because absurd!!

The Great Christian Doctrine of Original Sin (1758), a tour de force against Pelagianism, so profound that John Murray was fascinated by it. The History of Redemption (finished in 1739, but first published in 1774) was his attempt at a “body of divinity on a entirely new principle.” In fact, it is a faltering stab at an elementary biblical theology.

To Princeton and Christ’s Sweet Presence

In 1757, the call to leave Stockbridge came from Princeton, New Jersey. The College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) had lost its President, Edwards’s son-in-law, Aaron Burr, to death. The father-in-law was sought by the revival party at Princeton as a replacement. Edwards reluctantly answered the call and in January 1758 left Stockbridge for the long, lonely horseback ride to Princeton. He was installed President Edwards on February 16.

When the threat of a smallpox epidemic was noised about, Edwards submitted to inoculation as a proposed preventative. Whether his lifelong constitutional weakness (like Calvin, Edwards was rarely “well“—“weak in body,“ as George Whitefield described him), the absence of his very attentive wife, the depletion from the arduous winter journey from Massachusetts to New Jersey—whatever the physiological cause, Edwards died from the inoculation on March 22.

Edwards was buried in Princeton cemetery where his gravestone stands as a mute witness to America’s only native-born genius (and he a theologian!). “The greatest thinker that America has produced“—James McCosh. “We are, with Edwards, in the hands of one of the great minds of world history“—Bruce Kuklick.

The name Jonathan Edwards continues to fascinate and alienate. Many, even in the Reformed movement, have a love-hate relationship with Edwards. He has been excoriated as an “incipient Arminian.” Such slander is as ignorant as it is vicious. And yet he is embraced for delaying the triumph of Arminianism for at least a hundred years (as B.B. Warfield pointed out). The unbiased reading of Edwards finds him a classic Calvinist (see the sympathetic treatment in John H. Gerstner, The Rational Biblical Theology of Jonathan Edwards, 3 volumes) with profound insights into historic Reformed truths.

Postscript

The standard biographies by Perry Miller (Jonathan Edwards), Ola Winslow (Jonathan Edwards, 1703-1758: A Biography), Patricia Tracy (Jonathan Edwards, Pastor) are complemented (and corrected) by Iain Murray (Jonathan Edwards: A New Biography). George Marsden’s newest is entitled Jonathan Edwards: A Life. But the sleeper in this biographical catalogue is M. X. Lesser, Jonathan Edwards (1988). Unfortunately out-of-print, Lesser masterfully interweaves biography with theological development (through succinct summaries of Edwards’s writings) in an uncannily scintillating manner. It is the finest brief outline of Edwards and his Christianity ever put to paper.

The Yale edition of The Works of Jonathan Edwards has now reached 19 volumes. More than 27 volumes are projected. Yet the final Yale edition of 27 tomes will be but half of what Edwards wrote. Were we to have the entire Edwardsean written corpus, it would reach to 55 volumes and beyond. A CD-ROM version of Edwards in toto is being discussed by Yale. Precocious; prolific; profound; protean indeed!

The Yale project is but one part of the living voice of the ‘Last Puritan’. But it is also the lives of men and women and children changed by the preaching, teaching and writing of Jonathan Edwards which will be his legacy until his Lord—until Jonathan Edwards’s sweet Lord Jesus Christ returns.

Rev. James T. Dennison, Jr. is Academic Dean at Northwest Theological Seminary, Lynnwood, Washington where he also teaches Patristics.