Holy Scripture maintains the fundamental doctrine that God takes the initiative and speaks to the human race in a number of ways. Two of the principal channels of the divine communication are mentioned in the opening sentence of the epistle to the Hebrews. The apostle calls our attention to a progression in the revelation from God, a movement from the lesser (the prophets) to the greater vehicle of revelation (the Son of God): “God, after He spoke long ago to the fathers in the prophets in many portions and in many ways, in these last days has spoken to us in His Son” (Hebrews 1:12a).

The biblical writer draws our attention in this statement to the fundamental importance of the Old Testament prophets, that long succession of men of God beginning with Moses and going all the way to the time of the prophet Malachi. God, he assumes, did not speak directly to the Jewish fathers. Rather, He spoke through His chosen intermediaries, the prophets who were sovereignly chosen to convey the Word of God to the people. The prophetic revelation was not given all at once or on one specific occasion. The disclosure of the mind of God came little by little, to one generation after another. In addition, God did not use just one method in unveiling truth to His prophetic spokesmen. He used a variety of ways to communicate what He had to say—including the divine voice alone, visible manifestations, visions, and dreams.

Revelation by the Son

There is no question that the prophets were crucially important as channels of the mind of God as it was revealed to man. The point of the writer to the Hebrews, however, is that revelation has made a significant advance with the appearance of Jesus Christ. The arrival of the Messianic era means that God has now spoken in a way that is unprecedented in comparison to His previous ways of granting revelatory truth. In these last days, God has spoken to us in His Son, “whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He made the world” (Heb. 1:2b). The very person who created the world is now the one who has become the spokesman of God, the great prophet anticipated in the Old Testament. But even more than this, the Son is “the radiance” of God’s glory and “the exact representation of His nature” (Heb. 1:3). The Son, as the Greek text states, is the character of God’s nature. Just as the impress made by a seal exactly represents its original, so likewise, does the Son precisely reflect the divine nature of the Father.

Who Is God Himself

Because the New Testament insists upon the supreme dignity of the person of Christ, the true church throughout its history has refused to compromise on the issue of the identity of her Lord. The Creed of Nicea (AD 325) reflects the exegetical brilliance of the church fathers in its assertion that “the catholic and apostolic church” believes in “one Lord Jesus Christ” who is both “God of God” and “of one substance with the Father.” These three crucial Greek terms— homoousion to patri—accurately summarize the central New Testament message that the Son of God has the same divine nature that is possessed by God the Father. It is indeed the case that the homoousion formulation—that the nature of the Son is identical to the nature of the Father—was a decisive step in the church’s deepening understanding of the gospel message.

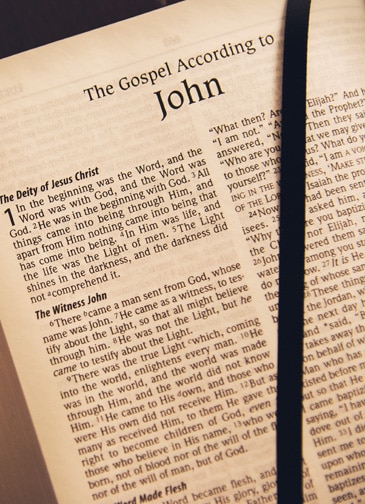

This perspective regarding the ultimate dignity of Christ lies at the heart of the New Testament. John, for example, began his Gospel with the affirmation: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (Jn. 1:1). The Logos (the revelatory Word of God), declared the apostle, was existing at the moment of creation, at the very beginning when God created the heavens and the earth. In addition, the Logos existed in a close relationship with God the Father. He was “with God.” And the Logos was much more than an exalted creature such as an angel. “The Word was God.” Furthermore, this pre-existent divine person was instrumental in bringing the creation into existence: “All things came into being by him” (Jn. 1:3). But even more remarkable in terms of the gospel is the statement that He came into the creation which He had made: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (Jn. 1:14). The revelatory Word took to Himself that which He was not. He became flesh, adding to Himself a fully human nature in all of its weakness, except for sin.

Exegeting the Father

Why did the Logos enter into human history? By presenting the testimony of John the Baptist, the apostle John directs our attention to the redemptive purpose of the incarnation: “Behold, the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world” (Jn. 1:29). But even before he refers to the salvific intention of the coming of Christ, John calls our thinking to the revelatory purpose of the Word becoming a man. “No man has seen God at any time,” John asserts (Jn. 1:18a). God is incomprehensible—incapable of being fully grasped by human understanding. But there is one person who has fully understood the Father, and he has even shared that understanding with us: “The only begotten Son, who is in the bosom of the Father, he has explained him” (Jn. 1:18b).

Since the Son was embraced within the loving arms of the Father from all eternity, there is no question that he fully knows who the Father is. The incarnation then makes it possible for the Son to share his knowledge of the Father with man who stands in such desperate need of that knowledge. The Son has done this very thing and has, quite literally, exegeted the Father. He has led the Father out before us so that we may come to know who the Father is. This was the very point that Jesus made in response to the request of Philip that he and the other apostles be allowed to see the Father: “Have I been so long with you, and yet you have not come to know me, Philip? He who has seen me has seen the Father” (Jn. 14:9).

Disclosing Pity and Grace

As we look into the face of Jesus, we look into the face of God. Jesus is the window through which we see God himself. As we see Jesus in action in the Gospels, we behold the love of God. Abraham Kuyper rightly stated that in the revelation provided in the incarnation God does not reveal himself to the sinner “antipathetically in His anger, but sympathetically…in His pitying grace” (Encyclopedia of Sacred Theology, 280). This indeed is the point made in John 3:17: “For God did not send the Son into the world to judge the world; but that the world should be saved through him.”

The crucial question in response to this divine revelation of mercy in the Son of God relates to every person’s individual response. There are, in reality, only two possible responses: faith (pistis) or unbelief (apistia). In unbelief, “the faith life of the sinner is turned away from God.” It “attaches itself to something creaturely, in which it seeks support against God” (Ibid, 280–281). Such unbelief is often reflected in trust placed in one’s own intellectual prowess or in a personal history of benevolence and good deeds. In this situation, the sinner essentially dares God to condemn the achievements of human reason or the excellence of moral conduct. To challenge God in such a way is surely the height of arrogance and folly, for fallen human beings are “darkened in their understanding” (Eph. 4:18) and “there is none righteous not even one” (Rom. 3:10). In the response of faith, the heart of the believer embraces the Christ, his cross, and his righteousness as they are freely offered in the gospel. This is true wisdom: to recognize one’s own desperate condition in the presence of the infinitely Holy, and then to reach out to Christ and to embrace him and his mercy.

The vital importance of each individual’s personal response is underscored in the Johannine declaration: “He who believes in him is not judged, he who does not believe has been judged already, because he has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God” (Jn. 3:18). Until this very hour, mercy and forgiveness are offered to the one who turns to Christ in faith. How do you respond to him through whom God has spoken in these last days?

Dr. Mark Larson is the home missions pastor at Providence OPC in Aiken, South Carolina. He is a regular contributor to The Outlook.