Several important motifs in the book of Hebrews set it apart from the rest of the New Testament. Most prominent among them is the epistle’s unique emphasis on Jesus Christ’s priestly office as a fulfillment of the old covenant priesthood and the accompaniments of its religious order. In general, the writer of Hebrews offers resources of spiritual encouragement to a group of suffering Christians called to endure with courage their own banishment from Jewish religious institutions, including the synagogue and temple (Heb. 13:13). His inspired word of exhortation comes to lift their “drooping hands” and strengthen their “weak knees” (Heb. 12:12).

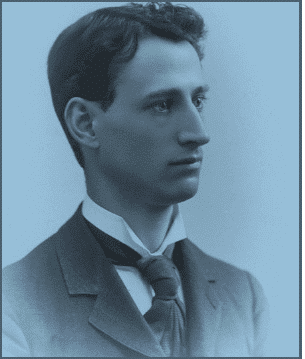

Distinguished biblical theologian Geerhardus Vos considers those texts that expound Jesus Christ’s heavenly priesthood to be particularly valuable for all Christians’ perseverance in this present age and thus crucial to the epistle overall. Such passages not only orient readers’ approach to the book of Hebrews but they also offer a profoundly insightful, and thus not merely academic vision for seeing the eschatological benefits of Christ’s eternal priesthood. Vos regards a proper understanding of the eschatological significance of Christ’s high priestly office essential for the development of a vibrant Christianity: its “whole character ought to be prospective; everything in it ought to be determined by the thought of the future . . . the inheritance of the final kingdom of God.”1

At the start of his treatment of Christ’s priesthood in Hebrews, Vos distinguishes between the coordinated offices of Christ as “Revealer” and as “Priest.” The opening verses of Hebrews reveal the importance of these closely linked roles. In verses 2–3 we read, God “has spoken to us by his Son,” and, “after making purification for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high.” Likewise, in 3:1, the Savior bears this dual title—the “apostle and high priest of our confession.” Since the single article and binds these two capacities closely together, they are vitally connected for the benefit of the Christian believer and the endurance of his confession. In order that we might be partakers of the heavenly calling of God in Christ, we must cast our gaze upon our eternal high priest.2 We will do that in this article by tracing the nature and benefits of Christ’s priestly office, granting particular attention to the eschatological blessings afforded believers on account of Christ’s ongoing heavenly session as a priest at God’s right hand. In addition to the broad text of Hebrews, Geerhardus Vos’s essays, sermons, and lengthier works on this subject will inform the overall flow of this article and the content of its conclusions.

The Nature and Benefits of Christ’s Heavenly Priesthood

Throughout Scripture, exhortations to new obedience often follow divine promises. In a similar manner, the significance of Christ’s heavenly priesthood relates to believers in the form of promise and exhortation. The assurances of God’s Word evoke genuine thanksgiving, which should result in grateful diligence to God’s righteous call. Hebrews 4:14 illustrates this common scriptural pattern: “Since then we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God, let us hold fast our confession.” Likewise, in verses 15 and 16 of the same chapter, we read, “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin. Let us then with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need.”

The exhortation to hold fast and maintain an enduring public confession of Christ raises important questions: How is this to take place in the believer’s life? What provisions are there for Christians to take an abiding stand for truth in the midst of this present evil age?

The inspired writer to the Hebrews saw the reality of Christ’s priestly office not only as a profound basis for the call to “stand firm” but also as the eschatological reality by which believers are strengthened for faithful endurance in this present age of tribulation. The enduring basis upon which Christians must and can “hold fast” is that “we have a great high priest who has passed through the heavens, Jesus, the Son of God” (4:14). Richard Gaffin reflects, “The secret of holding fast our confession is not something finally that we do, but what Christ has done and continues to do.”3 With this beautiful promise in mind, we turn our attention to the writings of Geerhardus Vos, who has helpfully examined the unique characteristics of Jesus Christ’s priestly office that make it so vital not only to the content of our confession but also to the enduring nature of our Christian profession.

In the first place, Vos draws our attention to what makes Jesus Christ’s priestly office so unique. The greatness and perfection of Christ’s priesthood is necessarily tied to and shaped by his eternal existence as the Son of God. Jesus belongs to a different class of priest, quite distinct from the earthly Levitical priesthood that served its purpose for an appointed term and then became obsolete (8:13). Jesus Christ is a priest forever after the order of Melchizedek (5:6), not based on a legal requirement or hereditary descent, “but by the power of an indestructible life” (7:16). Vos writes:

When Melchizedek appears in Scripture as a priest who derives nothing from ancestors or predecessors in office, but everything from his own royal personality, it is only because he has been by inspiration made alike in this respect unto the Son of God that he might prefigure the Son of God. Christ draws the qualification for his priesthood from his divine nature as well as from his human nature because it can be said of him that he is without beginning of days and end of life; therefore he remains a priest forever. He has his priesthood unchangeable because the power of an endless life is in him. He transcends and abrogates by his ministry the Levitical priesthood because in his, the undying person, he has forever assumed all its functions and prerogatives in an infinitely higher sense. Through the eternal Spirit, he offered up himself without blemish unto God and therefore he has perfected forever by one sacrifice all them that are sanctified.4

Interestingly, Vos notes that the unique temporal appearance of the priestly order of Melchizedek was due only to the eternal nature of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, whose priesthood, historically speaking, was patterned after it. He writes, “Now, if the greatness and eternity of the person of the Son of God determined the greatness and eternity-appearance of the figure of Melchizedek, and in consequence also determined the character of Melchizedek’s priesthood, and if further the priesthood of Christ was, historically speaking, copied after the order of Melchizedek, then it follows that it is ultimately nothing else but the divine eternal nature of the Son of God by which his priesthood is shaped and from which it derives its unique character.” Jesus Christ’s eternal sonship renders his priesthood distinct from every other type of priesthood.5

Vos’s observation of the unique nature of Christ’s priesthood directs our attention to the central theme of Hebrews—the comprehensive superiority of Jesus as the Son of God. The author of Hebrews states that he is superior to angels in virtue of his more excellent name (1:4). Christ’s honor and glory also surpass that of Moses, for he is the faithful steward over God’s house “as a son” (3:3–6). Centrally, the epistle to the Hebrews identifies Jesus Christ as the high priest whose service far transcends the qualities of the Mosaic priesthood. In virtue of his divine qualifications for priestly ministry, Christ introduces new hope through which believers can draw near to God. “Sworn in” to priestly office by a divine oath, Jesus is “the guarantor of a better covenant” since the old covenant made nothing and no one perfect (7:19–22).

The qualitative superiority of Christ’s priesthood provides better new covenant benefits that come to believers by way of guarantee. The former priests of the old covenant were prevented from continuing their priestly mediation because of their sin and consequent death. Christ, on the other hand, continues forever and “holds his priesthood permanently” after offering up himself for sinners “once for all” (7:23–24, 27). Because of his interminable intercession before God, he is “able to save to the uttermost those who draw near to God through him” (7:25). Jesus Christ, the eternal Son, who God appointed to make perfect forever those who respond in faith and obedience, surpasses the weakness of the human priesthood under the old covenant. “For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are being sanctified” (10:14).

In sum, the epistle to the Hebrews identifies Jesus Christ as the eternal Son of God who manifests his supremacy through his divine appointment as a better priest to a better priesthood that brings about better effects than that of the old covenant. Within the structure of the old covenant, the law made nothing and no one perfect (7:19). However, Christ’s sacrifice as the eternal high priest is sufficient to sanctify many “through the offering” of his body “once for all” (10:10).

Vos identifies a second key characteristic of Christ’s superior priestly office. The priesthood of the Son of God is necessarily better because he is a heavenly priest. Vos believes it is foundational to our apprehension of the blessings of Christ’s priesthood that he has “passed through the heavens” on our behalf (4:14). In fact, throughout the epistle to the Hebrews, the inspired author describes Jesus as belonging to the heavenly world, “in which everything bears the character of the unchangeable, the abiding.”6 Whereas the ministry of the high priest under the conditions of the old covenant properly belonged in location to the Holy of Holies, where the temporary priesthood alone could be officiated, so much more “the ministry of Christ belongs to heaven, where he alone can be a priest.”7

A principal benefit of Christ’s office is the superior locale where his priestly service transpires. Vos notes the clear spatial contrast between heaven and earth that exists within the epistle to the Hebrews in order to emphasize the ontological superiority of what takes place in heaven compared to the inferiority of earth. The point of the inspired epistle writer is that we have Jesus Christ, the high priest of a better covenant, who “is seated at the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in heaven, a minister in the holy places, in the true tent that the Lord set up, not man” (8:1–2, emphasis added). He labors for believers now and forever in the better heavenly tabernacle made by God himself, the “true tent.”

As much as the heavenly venue of Christ’s priestly work is superior, Vos would also have us see that God established a relationship of derivation between the earthly tabernacle and the heavenly tent. The earthly tabernacle derived its existence, pattern, and purpose from the heavenly tabernacle. In this way the earthly tent, though but a shadow, was necessarily a type of the heavenly reality. In fact, Christ’s priesthood is so tied to its heavenly location that “he would not be a priest at all” if he were still on earth (8:4). Vos comments:

His eternity and priesthood are seen most closely united in this—that for the main part the discharge of his priestly functions takes place according to our epistle in heaven where he ministers in his glorified state. The two are so inseparable that the author simply says: “If he were on earth, he would not be a priest at all.” But being in heaven, he is the one priest, and his priestly state partakes of the unchangeability which is the supreme law of that world. He is a priest upon his throne (to use an Old Testament phrase) and his throne, as we have seen, is everlasting since it stands at the right hand of the throne of God himself. Even when the priestly work in the specific sense of the application of his redemption shall have ceased, when it no longer will be necessary for him to make intercession or plead his merit for us because all sin and all consequences of sin shall have been removed—even then he will remain the everlasting High-Priest of humanity offering up to God the united adoration and praise of the redeemed race of which he is the Head.

Thus, it was necessary for the copies of the heavenly reality to be purified by the heavenly sacrifices themselves. Christ has not entered into mere types of the heavenly place for priestly labor, but into heaven itself. The heavenly is the true, original, abiding, and permanent place of atonement, while the earthly is an impermanent copy constructed by men. When Christ went “behind the curtain,” he entered into the heavenly sanctuary, just as the earthly priest once a year went into the Holy of Holies, which was a copy of God’s heavenly throne room (6:19). By implication, Christ’s ministry was not complete on earth. He had to ascend to the heavenly tent. Hence, his ascension was not a detour from his priestly labor. Rather, he is working—and he must work—from heaven, because entering the true and eternal Holy of Holies is the specific cosmic goal for all of Christ’s atoning work. He must continue to make intercession for us before God’s throne in heaven if we are to receive his saving benefits. Therefore, the book of Hebrews shifts our attention to a world in which heaven is not distant or inactive. Rather, it is where the most important action takes place. It is surely at the center of our religious existence. Indeed, says Vos, heaven is the primary locale of our atonement.

Our conception of Christ’s high priestly work often culminates at the cross. Vos agrees, of course, that the atonement for sin procured at the cross of Calvary is of central importance to Christ’s priesthood. At the same time, he cautions relegating the priestly work of Christ to his atoning work on earth. The author to the Hebrews places the emphasis of Jesus Christ as our priest in a heavenly context. Even with all the emphasis upon Christ’s earthly sacrifice for sin, the writer of Hebrews teaches that the death of Jesus Christ has something preliminary about it. Christ’s death, with all that it accomplishes, is still preparatory for what he is doing presently as our high priest in heaven. Vos comments that Christ, who is the supremely “heavenly person,” performed his act of atonement “in the milieu of heaven” since he was himself “a piece of heaven come down to earth.”8 Christ’s historic sacrifice for sin, while profoundly and necessarily temporal in nature, pertains principally to the age to come because of his heavenly priesthood. “Through the eternal Spirit he offered himself up to God, and therefore the acts of his priesthood, though spatially taking place on earth, really belonged to the sphere of the aionion. Its ideal reference was not to any earthly order of priesthood but in the ministry of heaven, for which it proved the necessary basis.”9 Moreover, if it is true that Christ offered his temporal sacrifice in regard to the sphere of heaven in order to appease the wrath of a holy judge, so too the intermingling of heaven and earth takes place for the Christian, who is made a partaker of the benefits of Christ’s death, resurrection, and ascension into heavenly glory. This intermingling takes place even now since “the Christian already anticipates his heavenly state here on earth.”10 Vos sees such anticipation of and interaction with the coming aionion on the part of the believer to be a “redemptive acquisition” stemming from the priestly work of Christ in heaven.11

Vos further identifies how Christ’s intercession at the right hand of God offers heavenly benefits of an eschatological nature for Christians living in the present age. Christ continually presents himself as our advocate before the Father in heaven, pleading our case upon the basis of his imputed righteousness. Because Christ offered himself in the heavenly sanctuary as the righteousness God requires of us, we can be assured that even in the midst of this present evil age we can “with confidence draw near to the throne of grace, that we may receive mercy and find grace to help in time of need” (4:16). Believers can also pray to God the Father with Christ as their intercessor, knowing that in Christ they are taken up into heaven to invoke God’s name and seek his mercy and grace.

Indeed, says Vos, such is the essence of the office of a priest. “A priest is one who brings near to God. His function differs from that of a prophet in that the prophet moves from God toward man, whereas the priest moves from man toward God. This idea is found in [Hebrews 5:1], where the author gives a quasi-definition of a priest: ‘For every high priest, being taken from among men, is appointed for men in things pertaining to God, that he may offer both gifts and sacrifices for sins.’ Thus a priest is one who brings men near to God, who leads them into the presence of God.”12

Vos more fully considers the true significance of being ushered into God’s

presence because of Christ’s priestly work. The task of any priest must be first to approach God in virtue of his unique authority in order to act as a representative for his people: “The priest brings men to God representatively, through himself.”13 The question arises, then, whether believers come near to God merely in and through the representation of another, enjoying no real connection with God themselves. Is there a sort of “imputed” fellowship with God through the mediator-priest, without the believer’s essential enjoyment of it? Vos responds by saying, “In the priest, the nearness to God is not merely counted as having taken place for the believers, as a mere imputation. Rather, so close is the connection between the priest and the believers that a contact with God on his part at once involves also a contact with God for them. The contact with God is passed on to them as an electric current through a wire.”14 Indeed, a believer’s intimate union with Christ by faith secures direct, permanent, and life-giving fellowship with God, who is in heaven.

Finally, an essential characteristic of a priest’s work, and that of Christ most specifically, is that “a priest does not content himself with establishing contact only at one point; he draws the believers after himself, so that they come where he is.”15 Christ draws his children into full and complete fellowship with God so that the age to come, at least in principle, has already arrived for the Christian.16 Vos explains:

Although in one sense the inheritance of this world lies yet in the future, yet in another sense it has already begun to be in principle realized and become ours in actual possession. The two spheres of the earthly and the heavenly life do not lie one above the other without touching at any point; heaven with its gifts and powers and joys descends into our earthly experience like the headlands of a great and marvelous continent projecting into the ocean.17

The author of the epistle to the Hebrews states that Christians actually have arrived at “Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem” (12:22). To regard this language as purely metaphorical is to pass over the true meaning of the author, Vos says. “Christians are really in vital connection with the heavenly world. It projects into their lives as a headland projects out into the ocean.”18 As a priest, Christ works instrumentally to procure actual fellowship between God and his saints. Believers truly enter into “the sanctuary of perfect communion with God” through their heavenly representative, Jesus Christ. Moreover, as the intercessor of the saints, Christ obtains and savors the fruit of his priestly labor on behalf of his people. In virtue of our union with him by faith, then, we have a foretaste of eschatological glory in and through Christ, the high priest. “He dwells with God as the first heir of the blessedness to which his ministry has opened the way.”19

Through his appearing, Christ is “the great representative figure of the coming aeon.” As a result, “the new age has begun to enter into the actual experience of the believer. He has been translated into a state which, while falling short of the consummated life of eternity, yet may be truly characterized as semi-eschatological.”20 Christ’s close identification with his people secures these eschatological blessings for them. Since Christ, through his voluntary sacrifice unto death, has become the head heir and already active participant of the eschatological state, Vos concludes, “He leads us in the attainment unto glory.”21 In virtue of their union with Christ, the heavenly priest, believers have a foretaste and already enjoy something of the newness of the coming age. They experience truly, though not completely, “the eternal side of the promises of God.”22 The book of Hebrews on the whole, then, seeks to demonstrate the necessarily better nature of Christ’s heavenly priesthood in order for believers to draw close to God “through a fresh and living way.”23

- Geerhardus Vos, “A Sermon on Hebrews 12:1–3,” Kerux 1, no. 1 (May 1986): 4–15.

- Geerhardus Vos, The Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1956), 91.

- Richard B. Gaffin Jr., “Christ, Our High Priest in Heaven,” Kerux 1, no. 3 (December 1986): 17–27.

- Geerhardus Vos, “A Sermon on Hebrews 13:8,” Kerux 4, no. 2 (September 1989): 2–11.

- Geerhardus Vos, “The Priesthood of Christ in Hebrews,” in Redemptive History and Biblical Interpretation: The Shorter Writings of Geerhardus Vos, ed. Richard B. Gaffin Jr. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1980), 153 (emphasis added).

- Geerhardus Vos, “The Eternal Christ,” in Grace and Glory: Sermons Preached in the Chapel of Princeton Theological Seminary, by Geerhardus Vos(Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1994), 204.

- Vos, “Priesthood of Christ in Hebrews,” 160.

- Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 114.

- Geerhardus Vos, “Hebrews, The Epistle of the Diatheke,” in Redemptive History and Biblical Interpretation: TheShorter Writings of Geerhardus Vos, ed. Richard B. Gaffin Jr. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1980), 220.

10. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 114.

11. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 114.

12. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 94.

13. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 95.

14. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 95 (emphasis added).

15. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 95.

16. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 52.

17. Vos, “Sermon on Hebrews 12:1–3,” 4–15.

18. Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 51.

19. Vos, “Priesthood of Christ in Hebrews,” 137–38.

20. Geerhardus Vos, “The Eschatological Aspect of the Pauline Conception of the Spirit,” in Redemptive History and Biblical Interpretation: The Shorter Writings of Geerhardus Vos, ed. Richard B. Gaffin Jr. (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1980), 92.

21. Vos, “Hebrews, the Epistle of the Diatheke,” 214.

- Vos, Teaching of the Epistle to the Hebrews, 21.

23. Vos, “Priesthood of Christ in Hebrews,” 141.

Mr Timothy R. Scheuers is a graduate of Mid-America Theological Seminary in Dyer, Indiana.