How can the US Congress prevent the establishment of religion while also insuring the free exercise of religion? Are concepts such as justice and rights inherently religious? (The American Declaration of Independence states that rights come from the Creator.) How can we fully discuss issues such as prayer in public schools, abortion and civil rights without reference to religion? Political questions of this sort are of much greater importance to our society in the long run than a middle class tax cut. But where do we go for help in thinking through such questions?

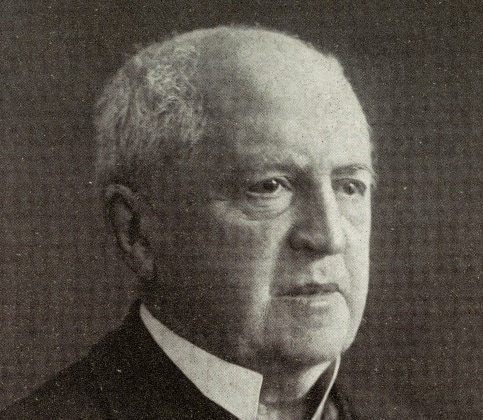

One source of help can be found in that profound Dutchman, Abraham Kuyper (1837–1920). Kuyper was one of the most remarkable Reformed men of the modern era. He was both a powerful thinker and an effective activist. He was a minister and churchman, a professor and theologian, a writer and newspaper editor, a politician and statesman. In the political arena he reorganized the Anti-Revolutionary Party and made it a potent force in national politics in the Netherlands. He also founded a daily newspaper, De Standaard, to give expression to his political views. He served in parliament and as prime minister (1901–1905).

Kuyper expressed his political his political ideas in numerous writings during his lifetime. The most accessible of Kuyper’s work for the English reader is the famous Stone Lectures that Kuyper delivered at Princeton University in 1898. In those six lectures Kuyper sought to crystallize his thought on a variety of topics: “Calvinism a Life-system,” “Calvinism and Religion,” “Calvinism and Science,” “Calvinism and Art,” “Calvinism and the Future,” and of special interest for our purposes, “Calvinism and Politics.”

The lecture on politics not only demonstrated Kuyper’s knowledge of traditional Calvinist reflection on the subject, but also his knowledge of recent history and the changing modern world that the Calvinist confronted in the late nineteenth century. He spoke of “the battle of the ages between Authority and Liberty”1 as a driving force of political history in our fallen world. In paradise there was a perfect balance between authority and liberty. But in the fallen world authority tends to tyranny and liberty to license. This basic battle, Kuyper argued, manifests itself in different forms in different periods of history.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In the Middle Ages the church sought to direct the state in the balance of authority and liberty, but that in itself was a form of tyranny expressed in institutions like the Inquisition. In the modem world the church was replaced either by the state or by popular sovereignty as the source of justice and of the appropriate balance between authority and liberty. But Kuyper argued that these modem conceptions of sovereignty were as faulty as the medieval. Popular sovereignty. as expressed in the French Revolution, led to chaotic liberty and the Terror. State sovereignty, as was emerging in German political thinking, led to oppressive authority. Both popular sovereignty and state sovereignty tended to tyranny.

Kuyper insisted that the only proper way to prevent tyranny of one kind or another was to acknowledge that authority and liberty were based in God’s sovereignty. He suggested three theses as the summary of his political faith:

1. God only—and never any creature—is possessed of sovereign rights, in the destiny of nations, because God alone created them, maintains them by His Almighty power, and rules them by His ordinances. 2. Sin has, in the realm of politics, broken down the direct government of God, that therefore the exercise of authority, for the purpose of government, has subsequently been invested in men, as a mechanical remedy. And 3. In whatever form this authority may reveal itself, man never possesses power over his fellow-man in any other way than by an authority which descends upon him from the majesty of God.2

For Kuyper the only way to guarantee and temper both authority and liberty was by recognizing that both derive from God.

Kuyper offered as historic examples the Dutch. English and American revolutions which—based on the sovereignty of God—both recognized legitimate authority and increased liberty. He contrasted them with the French Revolution—based on popular sovereignty—which led to greater tyranny. Had he lived longer, he might have used Nazi Germany as an example of the result of unlimited confidence in the sovereignty of the state.

PROBLEMS—SOLUTION

In founding his political thinking on the sovereignty of God, Kuyper sought to avoid two recurring historical problems: first, the tendency of the state to try to dominate all of life, and second, the tendency of the church to try to dominate the state.

The first problem Kuyper solved with his idea of sphere sovereignty. Human life is lived in various spheres such as family, business, science and others. Each of these spheres has a character derived from God and responsibility directly to God. Kuyper saw these spheres arising “organically” (we might say naturally) out of human life. He resisted the notion that the state with its “mechanical” (we might say artificial) power should seek to dominate each of these spheres. The spheres should develop according to their innate, God-derived principles, not as servants of the state.

The clearest example of this concept ofsphere sovereignty in Kuyper’s political life was the issue of the education of children. Liberal politicians in Kuyper’s day believed that education was the work of the state. The state should decide the values and content communicated in the schools. Kuyper responded by insisting that God had given children to parents and that parents had the responsibility to raise and educate their children. The basic character of education was a matter that parents must decide for their children. The state had an interest in seeing to it that children were educated, but parents needed to choose the kind of school that their children would attend. Kuyper succeeded in getting tax support for all schools to aid parents in making that choice.

As the issue of education shows, the state does have responsibilities in relation to other spheres of life. Kuyper summarized his position:

[The state] possesses the three-fold right and duty: 1. Whenever different spheres clash, to compel mutual regard for the boundary lines of each; 2. To defend individuals and the weak ones, in those spheres, against the abuse of power of the rest; and 3. To coerce all together to bear personal and financial burdens for the maintenance of the natural unity of the State.3

But the state must not move beyond these limits. When the state recognizes these limits it properly asserts its own God-given authority and the God-given liberty of society to develop apart from state domination.

The second problem Kuyper addressed was the problem of church domination of the state. Does the idea of state recognition of divine sovereignty imply subservience of the state to the church? Kuyper insisted that it did not. He was no theocrat. “A theocracy was only found in Israel, because in Israel, God intervened immediately.”4

He taught that the state as a sphere was itself directly responsible to God. The church must be free to be the church and the state must be free to be the state. As the church is not competent to decide many political matters, so the state is not competent to decide which is the true church. In the state the sovereignty of God is not expressed by establishing one true church, but in God’s Word ruling “through the conscience of the persons invested with authority.”5

Kuyper did believe that God should be formally recognized as sovereign in the state. He said of the magistrates:

They have to recognize God as Supreme Ruler, from Whom they derive their power. They have to serve God, by ruling the people according to His ordinances. They have to restrain blasphemy, where it directly assumes the character of an affront to the Divine Majesty. And God’s supremacy is to be recognized by confessing His name in the Constitution as the Source of all political power, by maintaining the Sabbath, by proclaiming days of prayer and thanksgiving, and by invoking His Divine blessing …the fact of blasphemy is only then to be deemed established, when the intention is apparent contumaciously to affront this majesty of God as Supreme Ruler of the State.6

At this point Kuyper’s American reader may pause and wonder if he is as modern as we first thought. And indeed some of the nineteenth century character of his reflections can be seen at this point. Kuyper assumed that he was speaking in a context where Christianity was dominant, and the pressing ecclesiastical question was whether one denomination would dominate others. He spoke in an American context where many political documents recognized the supremacy of God, where the Sabbath was protected by law and where the government did call people to prayer regularly.

Kuyper rightly saw the value of various churches’ freely and by spiritual means presenting their truth claims to society. He stated: “The churches flourish most richly when the government allows them to live from their own strength on the voluntary principle.”7

CONTEMPORARY APPLICATIONS

Kuyper also recognized that politics must be related to historical circumstances in the efforts to create a just society.8 He was no naive utopian or abstract theorist. Although he did not anticipate the much greater religious and cultural diversity of America today, he would have seen the challenge as an intriguing one. While it is not clear how he would have worked out the details, it is clear that he would still have insisted that the sovereignty of God ought to be recognized in the state and that the state should not coerce citizens in matters of religious conviction and affiliation. Balancing these two ideals is not easy as recent American experience with school prayer, abortion, civil rights and other issues shows. But secularist efforts to remove God from the public arena has already demonstrated the tyrannical tendency that Kuyper feared. (For an interesting and moderate discussion of some of these issues, see Stephen L. Carter, The Culture of Disbelief, New York, 1993.)

Kuyper would have read with understanding and general approval the amazing essay that appeared recently in Time magazine calling for a restoration of prayer in the public schools. Richard Brookhiser wrote his essay entitled “Let Us Pray”9 to argue that a sensible reading of American history points to the propriety of restoring prayer to the schools. He noted that the day after the House of Representatives passed the First Amendment to the US Constitution, the House officially called for a day of thanksgiving and prayer in the land. Brookhiser also offered a more theoretical argument in combination with the historical one:

Men have imagined other sources for their rights besides the Almighty. The Declaration mentions “the Laws of Nature.” But it immediately adds, “…and of Nature’s God.” Wisely so. The past 200 years have shown that nature is a distressingly malleable concept. It is the philosopher’s parlor trick to collapse it into history (nature in time) or will (nature in us). When such philosophies seeped into politics they spawned communism and Nazism. It is also true that God—and various gods—has covered a multitude of political sins over the millenni. But in the modern world, rights fare best when they are derived from a Source men fear to tamper with.

Kuyper in a much fuller way anticipated these sentiments.

Abraham Kuyper remains for us as Reformed Christians a fascinating political analyst for several reasons. The issues he examined are still very much with us. He saw the big picture in the development of western civilization in a very helpful way. His commitment to liberty of conscience and multiformity while expressed in a rather Romantic, nineteenth-century way is still valuable today. But most importantly his determination to recognize God as the source of all true authority and all real liberty is as true and necessary today as ever.

FOOTNOTES

1. Abraham Kuyper, Lectures on Calvinism, Grand Rapids, Michigan (Eerdmans), 1975, p.80.

2. Ibid., p. 85.

3. Ibid. , p. 97.

4. Ibid. , p. 85.

5. Ibid., p. 104.

6. Ibid., p. 103.

7. Ibid., p. 106.

8. He wrote of the need to “reckon with the effects of historical conditions,” ibid. Time., (December 19, 1994), p. 84.

Dr. Godfrey, President and Professor of Church History at Westminster Seminary in CA, is a contributing editor of The Outlook.