Few Christians in North America, at least among those who follow developments in the churches, are unfamiliar with the writings of Hal Lindsey (The Late Great Planet Earth), the Scofield Reference Bible or an institution like Moody Bible Institute. More of them are probably familiar with the subject of the “rapture,” as it is known in short-hand, than any group of Christians at any previous period in the history of the church. Many are keenly interested in the historical developments of the twentieth century, most notably the restoration of many Jews to their ancient homeland in Palestine, regarding these developments as portents of the close of the present age and the return of Christ. With the return of the Jews to Palestine, one of the most important preconditions for the coming millennium has been met—at least, so many Christians believe.

Though there are many other aspects of dispensational pre-millennialism which have become commonplace, particularly among conservative or fundamentalistic evangelical churches in North America, these alone are sufficient to illustrate the widespread influence of that view of the millennium known as “dispensationalism” or, perhaps more accurately, “dispensational pre-millennialism.”

This understanding of the millennium, though increasingly being abandoned or significantly modified, remains a highly influential and significant one. Reformed Christians have the responsibility not only to be aware of this view and its influence, but also to understand where it departs from the historic biblical and Reformed view of the millennium.

A BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Unlike historic pre-millennialism, dispensational pre-millennialism is a relative newcomer to the debate regarding the millennium. Though the language of “dispensations” or “economies” in the history of redemption has been used throughout the history of the church, only more recently has this language become common coin due to the growing influence of this millennial position.

The story of modern dispensationalism really begins around 1825 A.D. when several dissenting groups withdrew from the established churches of the British Isles. Among these groups were the “Plymouth Brethren” of Plymouth, England. An influential leader of the Plymouth Brethren was an Irishman by the name of John Nelson Darby. Darby established himself as an influential Bible teacher and, through his many writings and lecture circuits, introduced many of the features of what would come to be known as dispensationalism.

Though there were a number of influential ministers and Bible teachers who followed Darby’s interpretation of the Bible, the single most important figure in the subsequent growth and spread of dispensationalism was Cyrus I. Scofield. Scofield was a Congregationalist minister in the United States who had heard Darby lecture and embraced many of his views. Although Scofield’s training was in law and not in theology, he prepared his own study Bible with extensive notes placed throughout the Scriptures. This Bible, known popularly as the Scofield Reference Bible, was first published in 1909 and became the single most important means in the spread of dispensationalist teaching. Many who have used this Bible and its second, revised edition, tend to read the Scriptures in terms of the notes and interpretive comments found throughout its pages.1

Next to the influence of Darby and Scofield, nothing contributed more to the spread of dispensationalism, especially in North America, than the emergence of a number of fundamentalistic Bible institutes and colleges in the early decades of the twentieth century. Many of these Bible institutes and colleges were established by conservative or fundamentalistic Christians who opposed the liberalism and modernism of many mainline church institutions. Their commitment to a dispensational and literal reading of the Bible was often fortified by the conviction that alternative views were merely the fruits of an unbelieving approach to the Scriptures. To this day, much of the influence and spread of dispensationalist teaching is due to the work of these institutions. Among those institutions that remain dispensationalist or predominantly dispensationalist, the following require mention: the Philadelphia College of the Bible (founded by Scofield), Moody Bible Institute, Dallas Theological Seminary (the largest dispensationalist Seminary), the Master’s Theological Seminary, the Bible Institute of Los Angeles (BIOLA) and Talbot Theological Seminary, Grace Theological Seminary and Western Conservative Baptist Seminary. Of those influential or well-known ministers and theologians who hold a dispensationalist view today, the following are only a sampling: John F. Walvoord, Dwight Pentecost, Charles Ryrie, John MacArthur, and Charles Swindoll.

Despite the recent development of dispensational premillennialism, and despite some evidence of a waning of its influence and popularity.. this understanding of the millennium remains the majority opinion among many conservative Christians, especially in North America. Indeed, in many places it is still regarded as a kind of litmus test of commitment to the truthfulness of the Scriptures. Those, for example, who do not embrace dispensationalism are often regarded with suspicion by dispensationalists, since their view of Scripture is suspected as being something less than it should be.2

THE MAIN FEATURES OF DISPENSATIONALISM

In some respects, to summarize the main features of dispensationalism in brief form is an act of folly. There are so many varieties of dispensationalism that it has become impossible to keep track of them all. Moreover, there are clearly discernible stages in the history of modern dispensationalism, in which increasingly the old dispensationalism has been modified and in some cases even overturned. Despite these difficulties however, I believe there are some primary features of dispensationalism that continue to distinguish it as a particular view, even amidst many variations. Discernible within the variations or movements, common themes can still be detected.

The idea and terminology of “dispensations”

Perhaps the simplest place to begin in summarizing the main tenets of dispensationalism is with the name itself. What is meant by “dispensationalism” or “dispensation”?

This term derives from a biblical term from which we get the English word, “economy” (compare Eph. 1:10; 3:2; Col. 1:25).3 It refers originally to the arrangement or manner in which a household is administered. In dispensationalism, this term is used to describe the various ways in the history of redemption by which God regulates man’s relationship with Himself. In the old Scofield Bible, a dispensation is defined as “a period of time over against a redemptive economy.” A more recent publication of dispensational authors defines a dispensation as “a particular arrangement by which God regulates the way human beings relate to Him.”4 In the course of God’s administration of history, spanning the period from the creation of man before the fall to the ultimate consummation of history at the end of the millennium, God has employed a diversity of arrangements or stewardships in regulating His dealings with His image-bearers.

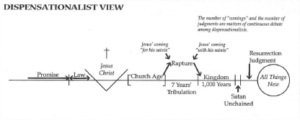

Though there is some debate within dispensationalism regarding the precise number and significance of these different dispensations, the most common position distinguishes seven such dispensations or economies: the dispensation of innocency from creation until man’s expulsion from the garden of Eden; the dispensation of human conscience from man’s expulsion until the great flood; the dispensation of human government from the time of the flood until the calling of Abraham; the dispensation of promise from the call of Abraham until the giving of the law at Sinai; the dispensation of the law from the time of Sinai until the crucifixion of Christ; the dispensation of the church from the cross of Christ until His coming “for His saints”; and the dispensation of the kingdom or the millennium when Christ reigns over restored Israel on David’s throne in Jerusalem for one thousand years. Within this dispensational conception of the history of redemption, each successive dispensation is introduced to further God’s purposes in a distinct manner and with respect to a particular people. The most important of these dispensations are clearly the last three, the dispensations of law, of the gospel, and of the kingdom.

One especially difficult question that arises in connection with the distinguishing of these various dispensations is whether there is one way of salvation, indeed One who is Savior; during these different periods. Though the implication of the original definition of a dispensation (and, I might add, the popular form in which dispensationalism is often taught and believed) seems to be that there are several ways of salvation, official statements today of dispensationalism will typically deny this conclusion. For example, in the doctrinal statement of faith of Dallas Theological Seminary, Article V dealing with “The Dispensations,” declares that “according to the ‘eternal purpose’ of God (Eph. 3:11) salvation in the divine reckoning is always ‘by grace through faith,’ and rests upon the basis of the shed blood of Christ.” This doctrinal affirmation actually represents a tendency in more recent expositions of dispensationalism which has been to modify or minimize an earlier, more sharp division of the economy of redemption into distinct administrations.

The uniqueness of the church

Within the broad framework of this dispensational view of history, historic dispensationalism insisted upon the uniqueness of the church, especially its distinction from Israel and God’s dealings with Israel before and after the dispensation of the church.

In its earliest and perhaps most blatant expression, this view argued that Christ began His ministry upon earth after His first coming by preaching the “gospel of the kingdom,” offering to restore the fortunes of national Israel and assume the throne of David in Jerusalem. However, when the Jewish people of His day rejected Him, the establishment of the kingdom of heaven was postponed and God commenced the dispensation of the church. The dispensation of the kingdom of heaven, because it has to do with God’s purposes for earthly Israel in a literal, Messianic kingdom, has now been “put on hold,” as it were, so that God’s purposes for the church might be realized. This accounts for the description of the church dispensation as a kind of parenthesis in the course of the history of redemption, a dispensation during which God’s peculiar dealings and purposes for Israel have been delayed or put off until they can resume again in the future.

With the suspension of God’s dealings with His earthly people, Israel, there is revealed, after the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ, what is often termed the “mystery” phase of the kingdom of God. This mystery phase unveils the peculiar purposes of God to gather in this present dispensation a predominantly Gentile people, the church, through the proclamation of the gospel to the nations and the call to faith and repentance. This is the “mystery” of the gospel taught, for example, in a passage like Colossians 1:25–27: though hidden from His people throughout all preceding dispensations in the economy of redemption, God has now made it known through the gospel that He has, alongSide His earthly people, Israel, a heavenly people, the church. This period or mystery phase of the kingdom of God coincides, according to dispensationalism, with the period between the 69th and 70th weeks of Daniel 9:24–29, the period from Pentecost, the birth of the New Testament Gentile church, and the “rapture” of the saints at Christ’s coming.6

Old Testament prophecies and the church

It is at this point that one of the most significant features of dispensationalism comes into full view: tile sharp separation made between God’s earthly people, Israel, and His heavenly people, the church, a separation which informs an all–embracing method of reading and understanding the Bible.

According to dispensationalism, the prophecies and promises of the Old Testament regarding Israel do not find their fulfillment in the dispensation of the church but in the dispensation of the kingdom or millennium yet to come. These prophecies and promises, which have to do with earthly blessings (a new Jerusalem, a restored Davidic kingdom and throne, universal peace among the nations, economic and material blessing, the restoration of Israel to the land of promise), have to be interpreted Iiterally and not spiritually or allegorically. And since they have not and cannot be literally fulfilled in terms of the present dispensation of the church, they must await their fulfillment when God’s purposes for Israel re-occurrence. Because the earthly, national and political aspects of God’s promises to Israel were not fulfilled at Christ’s first coming—when His own people rejected Him – they await their fulfillment during the dispensation of the millennium.

This is one of the most distinctive features of dispensationalism and its approach to the interpretation of the Scriptures: its insistence upon a literal hermeneutic or manner of reading the Bible’s promises in the Old Testament. If the Old Testament promises a rebuilt temple (Ezekiel), the temple in Jerusalem must be rebuilt. If the Old Testament promises that David’s Son will sit upon his throne (2 Samuel), this throne must be located in a literal Jerusalem still to come. If theOld Testament speaks of a renewed creation in which prosperity and peace will be enjoyed (Isaiah), then this must be fulfilled during a literal, earthly period of Christ’s reign upon this earth. It is simply inadequate to interpret these promises as having been or being fulfilled in the present age. Were that the case, so dispensationalism argues, the language of Scripture would no longer be reliable or literally true?

The only solution available is one which treats the Old Testament prophecies and promises as directed to a future age in which God’s purposes for His earthly people will be realized in history, the dispensation of the millennium. Furthermore, the fact that God’s dealings with the church do not fulfill Old Testament expectation only confirms that they are part of that hidden or mystery phase of the kingdom which God had purposefully kept concealed from His Old Testament people, Israel.

The pre-tribulational rapture of the church

If God’s dealings with the church are a kind of parenthesis or interruption of His dealings with Israel, the obvious question for dispensationalists is: how do you anticipate God will resume His dealings with Israel in the future?

At this point, the dispensationalist argues that the church dispensation will be concluded at the time of the rapture or Christ’s coming “for His saints.” A distinction is often made between this rapture or parousia in which Christ will come “for” His saints, and a later (seven years later) return in which Christ will come “with” His saints. Some early dispensationalists even argued that the first phase or rapture is always termed in the New Testament Christ’s “coming” (parousia) or “appearing,” and that, Similarly, His return is always termed Christ’s “revelation.” More recent dispensational writers acknowledge that this sharp distinction in the use of terms for Christ’s return cannot be maintained.

Furthermore, most dispensationalists believe that the “rapture” referred to in 1 Thessalonians 4:17 will occur before the period of “Great Tribulation.” They hold, accordingly, a view known as pre-tribulational rapturism.8 At the rapture, the “blessed hope” of every Christian, resurrected believers and transformed believers will be caught up with Christ in the clouds to meet Him in the air. Thereupon the body of believers, the raptured church, will go with Christ to heaven to celebrate with Him the seven years of the marriage feast of the lamb. Meanwhile, the seventieth week of Daniel 9 will commence on the earth. This period will be a period of tribulation on the earth, the latter half being the period of “Great Tribulation” during the reign of the anti-Christ (the “beast out of the sea”). This period of Great Tribulation will witness the conversion of the elect Jews and be concluded with Christ’s final triumph at the Battle of Armageddon over Satan and his host.

The millennial kingdom

Thus, during this seven year period, God’s program and purpose for Israel will resume in earnest and issue in the one thousand year or millennial dispensation. At the return of Christ, the second phase of His coming after the seven year period of tribulation, the Jews, many of them gathered to their ancient homeland, Palestine, will for the most part believe in Him and be saved, fulfilling Old and New Testament prophecy (compare Romans 11:26). The devil will be literally bound and cast into the abyss for a literal period of one thousand years.

As with historic pre-millennialism, dispensationalism believes that the millennium will begin with the first of at least two resurrections, the resurrection of saints who died during the seven year period of tribulation and the remaining Old Testament saints. These saints, together with the raptured church, will live and reign in heaven, while the Jewish saints on earth will begin to reign with Christ from Jerusalem for a period of one thousand years.9 Two judgments will also occur at this time: the judgment of the Gentiles who persecuted the people of God during the seven year period of tribulation (compare Matt. 25:31–46) and the judgment upon Israel (compare Ezek. 20:33–38).10

The millennium that ensues at the return of Christ will be, according to the dispensationalist, a literal fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies of a future golden age on earth. Universal peace and economic prosperity will prevail. Christ will reign with His saints, Israel. upon the earth. However, there will still be the experiences of life and death, marriage and family. At the end of the millennium, nominal believers and others will join Satan in his “little season” of rebellion, only to be crushed under foot by Christ. The millennium will end with the resurrections of those saints who died during this period and the “second resurrection” of all the unbelieving. The unbelieving will be subject to the Great White Throne judgment and be cast with Satan into hell. All believers, the church and Israel, will then enter into the final state when the heavenly Jerusalem descends to the earth.

“PROGRESSIVE DISPENSATIONALISM”

In order to complete this admittedly brief sketch of dispensational pre-millennialism, mention must be made of a contemporary movement within dispensationalism known as “progressive dispensationalism.” This movement has introduced some considerable modifications into the older, more classical form of dispensationalism.11 Among the newer emphases of this progressive dispensationalism, the following are most important.

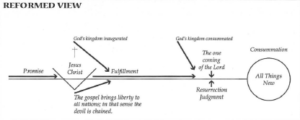

First, progressive dispensationalism, while retaining the distinction between the various successive dispensations, argues that ultimately God’s redemptive purposes bestow the same redemptive blessings upon the whole people of God, including Gentile as well as Jew. Without rejecting the distinction between the dispensation of the church and the earthly kingdom or millennium, progressive dispensationalism denies that the dispensation of the church is a kind of interruption or intrusion into the course of redemptive history. In fact, the spiritual blessings of salvation granted to the church will be the portion of the entire people of God in the final state. There will not be, in the final state, a separation between an elite class of Jews whose salvation is upon the earth, and a secondary class of Jews and Gentiles whose salvation is in heaven. All the purposes and blessings of salvation, spiritual and material, will terminate upon one people of God.

Second, progressive dispensationalism, as its name suggests, endeavors to emphasize more adequately the continuity and progress of the history of redemption. Rather than speaking of the dispensations in the redemptive economy as simply different, the progressive dispensationalist wants to emphasize the progress from one dispensation to the next, noting, where appropriate, the manner in which each successive dispensation fulfills and continues what was promised and begun in a previous dispensation. Consequently, though progressive dispensationalists will still distinguish the various economies, they will also acknowledge that these economies represent the historical realization of one kingdom program and purpose. Moreover, the differences between the various covenants, do not mean that there is not a genuine covenantal unity throughout the Scriptures.

Third, because of its willingness to acknowledge the progress from one dispensation to another in the history of redemption, progressive dispensationalism has modified the older dispensationalism’s view of the Old Testament promises and their fulfillment. Rather than insisting upon the literal and exclusive fulfillment of these promises during the millennium, progressive dispensationalism allows the fulfillment of these promises to occur in progressive stages. Many promises, for example, of the Old Testament are not only fulfilled at one level during the dispensation of the church, but find a further and related fulfillment in the dispensation of the millennia! kingdom.

Fourth, and perhaps most decisively, progressive dispensationaIism rejects the radical separation between two peoples and two purposes of God in the history of redemption. Ultimately, God has but one people, comprised of Jew and Gentile alike, and one program of salvation. However, multiform or diverse may be the progressive and successive working out of His redemptive purpose in the dispensations of redemptive history, the purpose of God is to save one people in Christ, a people whose salvation will be equally shared by all the nations and peoples of which it is comprised.

CONCLUSION

A careful study of progressive dispensationalism suggests that, in many ways, it represents a departure from the classic form of dispensationalism and a return to what I termed in my last article, historic pre-millennialism. Those features of dispensational pre-millennialism that distinguish it from historic pre–millennialism—the strict separation of Israel and the church, the insistence that Old Testament prophecy has no fulfillment in the dispensation of the church, the understanding that the church is a kind of parenthesis in history—have all been largely abandoned by the progressive dispensationalists. It is hard to find any substantial difference between this modification of dispensationalism and its older and more historic cousin, classical pre-millennialism.

This does not mean, however, that the older dispensationalism has been abandoned or has no longer any viability. I suspect that the advocacy of progressive dispensationalism has been, until now, largely an academic pursuit among scholars who wish to retain their place within the broader orbit of dispensationalism. The older dispensationalism, only slightly modified, remains alive and vital for many believers and their churches. However, the fact that such a substantial revision of dispensationalism is underway, from within the ranks of dispensationalists themselves, does not bode well for the future vitality of the older dispensationalism.

FOOTNOTES

- The revised or New Scofield Bible was issued in 1967 and is the product of a nine-member committee of leading dispensationalist theologians. This revision re presents the predominant dispensationalist view, one in which some of the more extreme positions of the original dispensationalism have been muted. The revisions are not as radical, however, as those being promoted by present-day “progressive dispensationalists.” I will consider this more radical revision briefly in what follows

- If I may be permitted a brief autobiographical note, I can attest to this general suspicion often found among dispensationalists against those who do not hold this view. As a high school student, I attended a Baptist academy whose teachers were dispensationalists and whose students, if they carried a Bible with them, always carried the Scofield Bible (was there any other?). It was always a difficult assignment for me to prove to my teachers and classmates that my opposition to dispensationalism was not the product of a liberal or unbelieving view of the Bible!

- English translations will often render this word as “administration” or “stewardship.”

- Craig A. Blaising and Darrell L. Bock, Progressive Dispensationalism: An Up-to-date Handbook of Contemporary Dispensational Thought (Wheaton, IL: Victor Books, 1993), p.14.

- I use the language “kingdom of heaven” here purposefully. Many dispensationalists have argued that this language in the gospel of Matthew is sharply to be distinguished from the language, “kingdom of God,” since it concerns God’s earthly program for Israel, not His purpose for the church. The astute reader will immediately see what this means for the present relevance of the gospel of Matthew, including the Sermon on the Mount, for the New Testament church. Those portions of the Scriptures that are directly related to the dispensation of the kingdom of heaven, are not directly binding upon us in the present dispensation. It should be noted that, linguistically, there is no real difference in meaning between the language “kingdom of heaven” and “kingdom of God.” The former phrase, found in the gospel of Matthew, only confirms the Jewishness of Matthew the evangelist’s first audience. It was customary among the Jews to use this language, in part to avoid the too frequent and casual use of the name, “God.”

- If someone might object that the passage in Daniel makes no mention of this period between the sixty-ninth and seventieth weeks (after the “cutting off” of the Messiah), the response is predictable: no mention is made of it because it was previous to the revelation of the NewTestament, a “mystery” kept hidden from God’s people!

- One prominent application of this principle is the insistence that, when the Bible uses the word “Israel,” it must refer to the national people of God, the Jewish community, not the church community (comprised predominantly of Gentiles)!

- There are a few dispensationalists who advocate a “mid-tribulational,” and even fewer, a “post-tribulational” rapture. See Millard J. Erickson, Com temporary Options in Eschatology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1977), pp. 125–81.

- The literalistic understanding of dispensationalism is particularly evident in its insistence that even the temple sacrifices in the temple will be revived during the millennium (though they will not be expiatory or detract from the one sacrifice of Christ)! It is important to observe that classic dispensationalism even insisted upon a sharp separation between two peoples of God, so much so that during the millennium and even in the final state, there will be a spiritual people of God in heaven and an earthly people upon the earth! This has been modified in the revised dispensationalism, represented by the New Scofield Bible, and abandoned altogether by progressive dispensationalism.

- Perhaps this is the place to note that some ardent dispensationalists have distinguished no less than seven different judgments and seven different resurrections, depending upon the time and persons involved. These judgments are to be distinguished from the “Great White Throne” judgment that will occur at the end of the millennium, in which those who join Satan in His final rebellion will be condemned to eternal punishment.

- 11 In addition to the book of Blaising and Bock cited earlier (fn4), the following sources provide a good summary of this view: Craig A. Blaising and Darrell L. Bock, eds., Dispensationalism, Israel and the Church: The Search for Definition (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992); and Robert L. Saucy, The Case for Progressive Dispensationalism (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993).

Dr. Venema, Professor of Doctrinal Studies at Mid-America Reformed Seminary in Dyer, IN, is a contributing editor ofThe Outlook.