By: Simonetta Carr

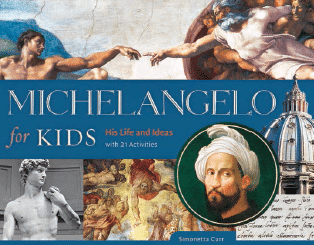

Michelangelo for Kids: His Life and Ideas with 21 Activities (Chicago Review Press, 2016)

Reviewed by: Rev. William Boekestein

Chicago Review Press does not publish Christian books. Their publishing submission guidelines explicitly state that they do not publish books in the area of religion. But in Michelangelo for Kids: His Life and Ideas with 21 Activities (for readers nine and up), Chicago Review Press has published an excellent Christian book.

Let me clarify. Michelangelo for Kids is written by a Christian author, about a Christian person, exploring Christian themes, and produced with a thoroughly Christian insistence on truth and excellence, beauty and order. So in partnering to produce this book, the author hasn’t hoodwinked the publisher and the publisher hasn’t compromised its guidelines. Instead, they have teamed up to provide author Simonetta Carr the well-deserved opportunity to use her talents to tell part of God’s story in a more nuanced way and to a more secular audience than her typical publishers ordinarily allow. The book preaches, but it doesn’t sound at all like a Bible sermon. Instead it invites readers to experience the book of God’s natural revelation, that “most elegant book wherein all creatures, great and small, are as so many characters leading us to contemplate the invisible things of God, namely His eternal power and divinity,” to borrow language from the Belgic Confession (Art. 2), which was written just a few years before Michelangelo’s death. This book is Christian because it is the kind of product upon which Christ could stamp his imprimatur, his “well done, good and faithful servant” (Matt. 25:23).

A secular publisher publishing a truly Christian book is doubly ironic. Tragically, much of what passes as Christian literature is not worthy of the title; too often, despite a shell of religion, the product does nothing to advance the reader’s understanding of God’s magnificence. In other words, a fair test of the quality of Christian writing is whether it meets the expectation of a reputable but non-religious publishing company. Michelangelo for Kids passes with gusto, from its clear and lively writing, to its copious striking images, to its overall feel of facility. You don’t have to be Christian to appreciate quality. A School Library Review raves, “This intelligently written, comprehensive, and fascinating account of the Renaissance icon’s life, art, personal and professional relationships, and prickly personality and the ways in which he navigated the religious and political upheavals of his time are handled smoothly and with sophisticated language.” Not only does this praise aptly describe Michelangelo for Kids, but also it helps set a much-needed benchmark for any writing that Christians (or anyone else) should care to embrace: When given the choice, we should settle for nothing less than writing that is intelligent, thorough, and fascinating.

Anyone who has written or read historical books understands the tension between getting the story right and using the story to grab readers by the hand and heart and draw them into the narrative. Carr does both. As readers learn about Michelangelo’s blossoming talents as a young man we can’t help feeling a desire to create. As the artist wrestles with disappointment, mortality, and God’s sovereignty, readers can easily join him in the strain.

Michelangelo (1475–1564) was a slightly older contemporary of Martin Luther—the artist was born almost ten years earlier and died almost twenty years later than the theologian. Like all of us they wrestled with the same questions. What is real beauty? How can a mortal experience immortality? They asked these questions in different contexts and did not answer them in exactly the same way. But we need to know both their stories. Both the artist and the churchman can help us know God.

The best historical writing—regardless of the topic—leaves the reader not only with a pocket full of facts about the historical plot, and an experiential acquaintance with the subject, but also a bolder, more robust outlook on life. After finishing the 130-page book I (and my children who read with me) know Michelangelo—not nearly exhaustively—but truly. In a small way, through her interactions with Michelangelo’s works, the author has also given the gift of beauty. Michelangelo has stretched our imaginations. The book has, if only in a small way, helped us to flourish. That is a testimony to good writing . . . no matter the subject guidelines of the publisher.

Rev. William Boekestein pastors Immanuel Fellowship Church in Kalamazoo, MI. His most recent book, Shepherd Warrior (Christian Focus 4 Kids, 2016), is a story of the exciting life of Ulrich Zwingli written for readers eight to fourteen years old.

By: Connie L. Meyer

Gottshalk, Servant of God. A Story of Courage, Faith, and Love for the Truth. (Reformed Free Publishing Association. 2015)

145 pages. $17.95 ISBN: 978-1-936054-88-6 Ebook ISBN: 978-1-936054-89-3

Reviewed by: Rev. Jerome Julien

Gottshalk of Orbais [c.806–c.868] is an important but sadly little known character in church history. Very few books deal with him and his contribution to the doctrines of the Christian church. Mrs. Meyer has written this as a book for young people, yet it is very readable for any age. In fact, every child of God would benefit from reading it. The illustrations, the endnotes, and even the inclusion of some of Gottshalk’s writings are helpful.

Why ought Reformed people know about Gottshalk? He stood for the Reformed truth of God’s sovereignty in salvation. As a monk, priest, and missionary in the medieval church he would give his life as a sacrifice for the truth of double predestination (election and reprobation). As a student of Augustine’s works, he was convinced that Augustine was correct in his teaching on this basic biblical truth. Yet, the Roman Catholic Church was becoming humanistic/man-centered in its approach to many teachings. Leaders objected to his teachings and writings so much that they had him cast into prison. Though Gottshalk’s letter concerning his teaching to Pope Nicholas I (who seemed to have some agreement with Gottshalk) was smuggled out of the monastery prison, we see no change in Catholicism of that day.

It can certainly be said that he was a man who was valiant for truth. Thus, this fine little book becomes a primer on predestination and it should be viewed that way. If there is any concern this reviewer has with this fine volume, it would be that more could have been made of Gottshalk’s missionary work and how that work fit right in with his views on double predestination. Many like to characterize those who believe in predestination as being against missions. Our ancient brother saw no contradiction.

Mrs. Meyer has done a great piece of work here, making Gottshalk’s role in church history much better known. Until this volume, as far as this reviewer knows, anything on him has been in scholarly volumes—many in a foreign language or in scholarly journals, with the exception being a fine chapter in Professor Herman Hanko’s Portraits of Faithful Saints.

Rev. Jerome Julien is a retired minister in the URCNA living in Hudsonville, MI, and serves on the Board of Reformed Fellowship. He and his wife, Reita, are members of Bethel URC, in Jenision, MI.