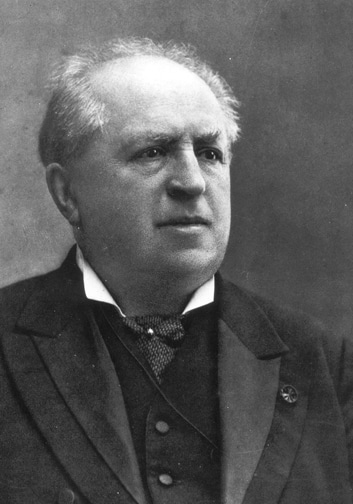

In my previous article, I noted that Kuyper has been a controversial figure within the Reformed community. During his own lifetime and afterward, Kuyper’s articulation of a Calvinistic worldview has provoked considerable debate. Evaluations of Kuyper’s position have ranged from enthusiastic approval to vigorous dissent, with any number of positions between these extremes. The number and variety of Kuyper’s critics attest to the importance of the issues he raised for the service of Christian believers in his day and ours.

Having considered some of the more common criticisms of Kuyper’s doctrine of the church and his principle of sphere sovereignty, we have yet to consider those criticisms that relate to Kuyper’s understanding of the antithesis and of common grace. Here too Kuyper’s viewpoint has evoked rather different responses. Indeed, something of the complexity of Kuyper’s thought is evident in his emphasis upon both the antithesis and common grace. Among those influenced by Kuyper, quite different approaches and viewpoints have been adopted, depending upon the role and prominence of one or another of these principles.1 Some have enthusiastically embraced Kuyper’s insistence upon the antithesis between faith and unbelief as it affects every area of life. As a result, their policy has been to vigorously separate from all illegitimate entanglements with the world in the area of worldly amusements, organizations and institutions and so on. Others have more affinity to Kuyper’s view of common grace and have adopted, accordingly, a more affirmative policy toward the world. Each of these policies can easily find support in Kuyper’s writings.

CRITICISMS OF KUYPER’S VIEW OF THE ANTITHESIS

One of the keynotes of Kuyper’s life was that of the antithesis between faith and unbelief. This antithesis between the truth and the lie, the kingdom of Christ and the kingdom of this world, cuts through all of life and profoundly influences human life at every level and in all of its expressions. There is no neutral place so far as the recognition and service of Christ as King is concerned. Whether it be in marriage, the home and family, the business enterprise, the school or academic institution, the political party, the labor union—in all the areas and spheres of life one either works “for the King” (pro Rege) or against Him.

For this reason, one of the distinctive fruits of Kuyper’s reforming activity in the Netherlands was the promotion of distinctively Christian institutions whose formative principles were based upon the Christian worldview. Not only in the Netherlands, but also in North America, those who have followed Kuyper have sought to establish separate Christian organizations in various life spheres.

Kuyper’s influence was far-reaching in the promotion of, for example, Christian schools at every level (from primary school to university), Christian labor unions, and Christian political associations. The consequence of this emphasis is known today in the Netherlands as a process of verzuiling (“pillarization”) in which the whole of society is structured along ideological lines with different groups (Reformed, Catholic, secularist) developing separate institutions to express their particular principles.2 Similarly, the conflicts within many Reformed communities regarding the subject of “worldly amusements” and the dangers of world-conformity were the product, at least in part, of a Kuyperian emphasis upon separation from all illegitimate entanglements with the principles and practices of the world.

Kuyper’s stress upon the antithesis and its implications for the separate development of Christian institutions has been criticized in several ways. One criticism often voiced is that Kuyper’s emphasis encourages a kind of isolationism in which the Christian community develops a radically separate form of existence in each sphere of life. By insisting upon the separate development of Christian institutions in every area of life, Kuyper’s worldview encourages pluralism within human society that unnecessarily and dangerously isolates differing communities from each other. As a consequence, there is little place for any bonds of community or society that bridge the differences between ideological or religious communities. This can lead, say Kuyper’s critics, to a kind of isolation from the world on the part of the Christian community that will be counter-productive to any leavening influence within society. Furthermore, within the academic sphere, Kuyper’s stress upon two kinds of science can lead to an obscurantism within the community of Christian scholars, one which rejects any accountability to or interaction with the broader world of scholarship.

A different, though related, criticism of Kuyper’s insistence upon the antithetical development of distinctively Christian institutions is the charge that it often produces an unrealistic, even triumphalistic, social policy. Advocates of Kuyper’s vision have often maintained that—no matter how impractical it might prove to be—the Christian community must establish its own organizations in order to be faithful in the service of Christ. Nothing less than a Christian political party or a Christian labor union, for instance, will answer to the need to honor Christ’s lordship, respectively, in politics and labor relations. Critics of Kuyper’s vision frequently argue that this approach is na’ive at best. grandiose at worse. It assumes that Christian believers not only can form such organizations, but also can expect them to make a real difference in society. But it is hardly possible in a country like the United States that a Christian political party could be formed that would have any meaningful impact upon the formation and implementation of public policy. Nor is it likely that—in spite of the brave talk about the transformation of this or that dimension of modern life—these efforts will make any appreciable difference in the patterns of western secular society. Often, it is alleged, these efforts result more in being conformed to than transforming the world.

It is difficult to respond to these criticisms of Kuyper’s emphasis upon the antithesis and its implications for Christian practice. Some of them do not so much address Kuyper’s position as distortions or one-sided approaches on the part of those who claim to be working “in his line.” Others represent a lack of appreciation for the biblical teaching that the believer and the believing community are to be separated from the world in order to be consecrated to the Lord’s service. Still others reflect the conviction that the transformation of individual believers is a more appropriate policy than the formation of Christian organizations which often become an obstacle to real transformation.3

However, in some cases Kuyper’s emphasis may produce the kinds of ill fruit described.

Ironically, the separation from the world which Kuyper advocated on the basis of his doctrine of the antithesis can become the occasion for a kind of isolationism which cuts the Christian community off from any meaningful (including evangelistic)4 engagement with the world. This is ironic in view of Kuyper’s emphasis upon separation from the world for the sake of a distinctively Christian practice in the world. Kuyper did not intend the formation of Christian institutions to be the means of escape from engagement in legitimate worldly vocations. Rather, he intended these institutions to be the means of expressing and exhibiting Christ’s lordship over all of life in the various life spheres. The kind of isolationist practice that characterizes some advocates of Kuyper’s principle of the antithesis represents a distorted and one-sided appropriation of Kuyper’s insights. This practice often reflects an appreciation for Kuyper’s emphasis upon the antithesis, but a rejection of his emphasis upon common grace.

One legitimate aspect of these criticisms of Kuyper’s understanding of the antithesis relates to the different situation Kuyper faced in the Netherlands at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. What Kuyper advocated and encouraged in terms of the separate development of Christian institutions in the Netherlands in this period is often impractical in North America at the end of the twentieith century. This is not a concession to a kind of pragmatism that measures what is proper by what is practical. But it is a recongnition that there were unique circumstances and developments in the Netherlands during Kuyper’s lifetime that cannot be replicated in North America in our day. Though the principles Kuyper articulated are of continuing significance, the policies that these principles recommend may be somewhat different. Though the formation of separate Christian organizations, where this is feasible and permitted, may be a preferred means to express the lordship of Jesus Christ in different areas of life, alternative means may in some cases have to be found by the Christian community today.5

COMMON GRACE AND “POSITIVE” CALVINISM

It is fitting that I should reserve to the last the doctrine of common grace as Kuyper developed it. No feature of Kuyper’s thought has been the subject of more sustained reflection or severe criticism than his understanding of common grace. No feature of Kuyper’s thought has provoked greater dissension among his critics. On the one hand, there are those who receive Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace as an important “corrective” or antidote to his at times extremist development of the principle of the antithesis. According to these critics, the doctrine of common grace blunts the sharp edges of Kuyper’s view of the antithesis, preventing the kind of isolationism and obscurantism of which I spoke in the preceding section. On the other hand, there are those who regard Kuyper’s development of this theme as a kind of “Trojan horse” within the camp of a Christian worldview. By developing and expanding the doctrine of common grace beyond anything known previously in the Reformed tradition, Kuyper opened the door to the very thing his emphasis upon the antithesis ought to have nailed shut — a policy of conformity to the world.

One of the remarkable features of the discussion of Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace is the prominent role this doctrine has played within the (Dutch) Reformed community in North America. Students of the history of the Reformed churches in North America are familiar with the debates regarding common grace, for example, that troubled the Christian Reformed Church in the early decades of the twentieth century and led to the formation of the Protestant Reformed churches.6 Though I will not enter into the history and course of these debates, these ecclesiastical developments reflect the intense and ongoing debate that Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace has evoked.

Among those who appreciate Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace, it is generally acknowledged that this doctrine allowed Kuyper to account for the possibility and propriety of engagement with the world at every level. Because common grace expressed God’s continued goodness toward the creation in upholding, maintaining and directing its life and development, Christians were obligated to continue to serve God within the full range of human life and culture. Because God by His common grace hindered and prevented the full expression of sinful rebellion in human life and culture, much that was good and praiseworthy could be found and appreciated by the Christian community in its use of the products of human culture. Common grace, according to Kuyper, accounted for the presence of institutions (the state), the progress of science and scholarship, the arts, and the like, which Christian believers are obligated to receive with gratitude and use in the service of Christ. However corrupted or distorted through human perversity and sinfulness, these fruits of God’s common grace in the preservation and development of the creation are not to be despised or wholly rejected. Common grace, therefore, provided Kuyper with a basis for encouraging Christian activity in the world rather than flight from the world. This doctrine provided the kind of balance Kuyper needed to prevent his understanding of the antithesis from spinning off in the direction of the kind of isolationism described in the preceding section.

Those who have little appreciation for Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace view this doctrine in an entirely different light. According to these critics, Kuyper not only failed to show any meaningful connection between his understanding of “particular” and “common” grace, but he also provided a basis by means of this doctrine for emasculating the antithesis of its power. By expanding the doctrine of common grace, Kuyper laid the foundation for the kind of positive Calvinism that has little eye for the antithesis between faith and unbelief, but a keen eye for all the ways the kingdom of Christ and of the world converge. This positive Calvinism finds much of the culture and scholarship of the world to be congenial to the Christian faith. It looks eagerly for common ground with the world and risks thereby accommodation to the allurements of worldly success and approval. Though it still speaks of the need to “transform” all of life, its practical policy is one of “conformity” to the dictates of contemporary culture and scholarship. Rather than seeking to distance the Christian community from the world’s patterns of thought and life, the mind of common grace looks upon the world and its products as benign and nonthreatening.

That Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace could give rise to such widely divergent responses ought to caution against too simplistic an evaluation of his position. However, it is striking to notice how Kuyper is criticized by some for emphasizing too much the antithesis. This criticism maintains that Kuyper’s doctrine of the antithesis can only lead to isolationism and radical separation from all worldly engagements. Others also criticize him for emphasizing too much the doctrine of common grace. This criticism then maintains that Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace can only lead to world conformity and accommodation to sinful human culture and scholarship. Two more conflicting sorts of criticism could hardly be imagined!

At the risk of being regarded as too much a “Kuyperian,” I would argue that these criticisms of Kuyper represent a kind of one-sided caricature of Kuyper’s worldview. Neither of them answers to the complexity and breadth of Kuyper’s full position, a position that resists playing off the antithesis against common grace as though these were inherently at odds. No doubt many of Kuyper’s followers have embraced one or another aspect of his thought — some emphasizing the Kuyper of the antithesis, others emphasizing the Kuyper of common grace. Kuyper’s legacy includes not only those who are sometimes termed “antitheticals,” but also those who are sometimes termed “positive” Calvinists. Each of these approaches can appeal to Kuyper against the other. But in so doing they confirm that Kuyper’s worldview was more complicated and rich than their own, one-sided worldview which offers, dare I use the term, a more “simplistic” handling of the issues Kuyper was addressing.

Now this does not mean that Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace is wholly satisfactory. There is some real ambiguity in Kuyper’s doctrine on the question of the relation between particular and common grace. In some of his formulations, Kuyper so emphasizes the working of God’s common grace that it seems to have a completely independent significance, unrelated to the purpose and working of God’s special grace in the salvation of His people.7 As a result, Kuyper does not always carefully articulate the significance of common grace as it provides a context for the accomplishment of God’s redemptive purposes. Nor does he provide an adequate account of the kind of interrelation that exists between the principle of the antithesis and the doctrine of common grace. It is not surprising, therefore, that students of Kuyper have been able to take hold of one or another of these emphases while rejecting or depreciating the other.

CONCLUSION

When I first consented to the request of the editors of The Outlook to write an article or two on Abraham Kuyper, I had no idea that this project would grow into a series of articles. However, now that I have come to the conclusion of this survey of Kuyper’s life and legacy, I am struck by how much more could be written! Much of what I have written has been rather general and abbreviated. Many things demand further discussion and reflection. But I will have to resist the temptation to do so here.

It has not been my purpose in this series to provide a complete account of Kuyper’s life. Nor have I provided anything like an adequate evaluation and critique of his articulation of a Christian worldview. Rather, I have written this series in commemoration of the 100th anniversary of Kuyper’s famous Stone Lectures at PrincetonTheological Seminary, with the hope that it will contribute in a small way to a renewal of interest in Kuyper’s life and legacy.

As the Christian community in North America, especially the Reformed community, confronts the challenges of the present day, Kuyper’s writings and ideas represent a rich resource of biblical and Reformed insight. They deserve to be read and pondered, as the challenge of presenting the Christian worldview confronts the forces and currents of contemporary culture. If withdrawal from the world and retreat from the challenge of modern scholarship are not viable options for us — as I believe they are not — then we have a great deal of hard work to do in carefully studying the resources of our tradition and articulating the catholic claims of the biblical worldview in our time.

For this reason, Kuyper’s legacy is not so much the ideas or principles he articulated, important and useful as they may continue to be. Nor is Kuyper’s legacy the extraordinariness of his life and labors. We do not pay homage to any person. Rather, Kuyper’s legacy lies in his insistence that we bring every thought and work captive to the obedience of Christ. There can be no rest for the Christian or the Christian community in relentlessly seeking to love the true and living God with all of our soul, mind and strength. This means not only that every thought be brought captive to Christ, but that every deed be tested by the standard of God’s kingdom and its righteousness. The Triune Redeemer who is the Creator of all things demands (and deserves) nothing less than that from us.

Kuyper’s legacy remains best expressed in his well known words, spoken on the occasion of the founding of the Free University: “[N]o single piece of our mental world is to be hermetically sealed off from the rest, and there is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry: ‘Mine!’”

FOOTNOTES

1. The Protestant Reformed churches, for example, have historically embraced Kuyper’s insistence upon the antithesis but rejected wholeheartedly his development of the doctrine of common grace.

2. See Peter S. Heslam, Creating a Christian Worldview, pp. 2–8, for a brief description of this process in Dutch society and its connection with Kuyper’s influence.

3. This last objection to Kuyper’s promotion of Christian institutions does not seem very significant. The failure of an institution to fulfill its promises (e.g. a Christian school) might simply call for renewed effort to improve the institution or form another, similar institution. Though no one should place their trust in such institutions, they are often a helpful means of acknowledging the lordship of Jesus Christ.

4. In this connection, it is interesting to note that Kuyper does not have much to offer in terms of the evangelistic and missionary calling of the church. Kuyper lived in a world very different from the one many of us face in North America at the end of the twentieth century. The terms often used to describe the contemporary situation, “post-modern” and “post-Christian,” would not describe the situation in which Kuyper worked. Whereas the Christian community today in the West faces a new missionary situation, Kuyper simply assumes the presence of a Reformed community of churches. He does not directly address the question of how the gospel should be communicated to a culture than has turned away from the Christian faith.

5. For example, in some circumstances “home schooling” may be preferable to the Christian school as a means of providing Christian education for the children of Christian parents. These circumstances could include: the absence of a good existing Christian school; inadequate financial resources for tuition; the strength and aptitude of the child’s parents for teaching at various levels; the unique circumstances of the child; political, cultural or legal obstacles to the establishment of a separate Christian school and others. It should also be noted that there might be circumstances where the preferred policy for the Christian community is one of withdrawal from involvement in some areas of modern life.

6. See James D. Bratt, Dutch Calvinism in Modern America (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, (984). pp. 37–54,93–122; and Henry Zwaanstra, Reformed Thought and Experience in a New World (Kampen: JH. Kok, (973). pp. 68–131. Bratt and Zwaanstra describe in considerable detail the debates within the Reformed churches (the Christian Reformed especially) in North America regarding Kuyper’s views and the doctrine of common grace. Both of these authors argue that different sectors of the Reformed community tended to emphasize one or another of Kuyper’s principles. Those who emphasized the antithesis are termed “antithetical” Calvinists by Bratt and “separatist” Calvinists by Zwaanstra. Those who emphasized the doctrine of common grace are termed “positive” Calvinists by Bratt and “American” Calvinists by Zwaanstra. Though these labels and party designations tend to oversimplify matters, they do help to sort out some of the debates and differences of emphasis that characterized conflicting groups within the Dutch Reformed community of churches.

7. See s. U. Zuidema, “Common Grace and Christian Action in Abraham Kuyper,” (in his Communication and Confrontation [Toronto: Wedge, 1971]), pp. 52–105, for a thorough evaluation and criticism of Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace. Students of Kuyper’s doctrine of common grace generally acknowledge that it remains an unfinished item on the agenda of Reformed theology. Cf. Edward Heerema, Letter to My Mother (Freeman, S.D: Pine Hill Press, (990). pp. 5–22. Heerema describes the doctrine of common grace as “unfinished business” so far as the history of the Christian Reformed Church is concerned.

Dr. Venema teaches Doctrinal Studies at Mid-America Seminary in Dyer, IN.