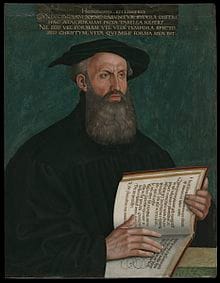

Heinrich Bullinger (1504–1574) is one of those Reformers of great fame and influence in the sixteenth century who has been largely forgotten in the twenty-first. He was roughly a contemporary of John Calvin, born five years before Calvin and living ten years longer. Who was Bullinger and why should we remember him on this 425th anniversary of his death?

Bullinger became the leading pastor in the city of Zurich after the death of Ulrich Zwingli, whom we might call the grandfather of the Reformed movement. Zwingli had come to the Reformation faith shortly after Luther, and along with Luther, was one of the most prominent leaders of the Reformation. Zwingli and Luther, while agreed on most points, disagreed strongly on the meaning of the Lord’s Supper. They had tried to resolve their differences at the colloquy of Marburg in 1529, but those efforts failed. Less than two years later in 1531, Zwingli and 24 fellow ministers of Zurich died in the Second War of Kappel defending their city against a Roman Catholic attack. The young Heinrich Bullinger (only 26 years old) was called from the relative obscurity of his teaching and preaching work in the neighboring town of Kappel, to one of the most important pulpits in the Protestant world.

Heinrich Bullinger was born on July 18, 1504, in the Swiss town of Bremgarten. He was the son of a Roman Catholic priest who lived in a stable relationship with his mother which was regarded as normal in many parts of pre-Reformation Europe. He received a good education in Renaissance learning in his early years and attended the University of Cologne between 1519 and 1522, earning his B.A. and M.A. degrees. He was in Cologne when the theological faculty there publicly burned Luther’s books on November 15, 1520. That fire sparked Bullinger’s interest in theology, leading him to read Luther, the New Testament, and in 1521, Philip Melanchthon’s new systematic theology, the Loci Communes. By the end of his studies in Cologne, he had embraced the new theology.

He returned to Switzerland and took up a teaching post at a monastery school in Kappel. There he found time to study the Scriptures and write commentaries on New Testament books. He heard Zwingli preach for the first time in 1523 and participated in the reform of the church in Kappel in 1525. He accompanied Zwingli to Bern in 1528 where he met key Reformed leaders: Berchtold Haller of Bern, Martin Bucer of Strassburg, and Guillaume Farel who would later introduce the reform to Geneva. Zwingli invited Bullinger to accompany him in 1529 to the meeting with Luther, but he declined, being very busy with his new preaching responsibilities in Kappel. That year he also married a former nun with whom he would have eleven children.

Of his many works, one of the better known was the First Helvetic Confession (1536) of which he was one of the principal authors. That confession guided many of the German-speaking Swiss churches for about thirty years. Even more influential was his collection of sermons known as the Decades. This collection of sermons, ten in each section, was published in final form in 1558. These sermons were widely translated and read throughout Europe. The leaders of the Anglican church especially treasured these sermons and they were required reading for the clergy in England for many years.

Calvin and Bullinger often corresponded and worked closely together to promote the unity of the Reformation cause. In 1549 they led their churches to accept the Consensus Tigurinus (the Zurich Agreement) which they had prepared. This statement signaled a common confession on the Lord’s Supper embraced by Zurich and Geneva.

Some scholars have suggested that Bullinger represented another Reformed tradition from the one developed by Calvin.1 This suggestion is not just about the Lord’s Supper (where some think that Bullinger is closer to Zwingli than Calvin) or about church discipline (which Bullinger entrusted ultimately to the civil magistrate rather than to the church). Rather this interpretation of Bullinger argues that he had a bilateral view of the covenant (distinct from Calvin’s monolateral view) and that he rejected Calvin’s doctrine of reprobation in favor of a single, positive decree of predestination. While there are different emphases in the theologies of Bullinger and Calvin, the scholarly argument that sees them in opposition to each other is very much overstated.

We find the clearest summary of Bullinger’s theology in his most famous work, and the only one much known today, the Second Helvetic Confession, written in 1561 and published in 1566. Many of the Reformed churches of Europe approved this confession and it was officially adopted by most of the German-speaking Swiss Reformed churches. The Hungarian Reformed Church also adopted it.

The Second Helvetic Confession is lengthy, running to 76 pages in one English translation, and divided into 30 chapters. It is quite theologically elaborate, with many quotations from the Bible and very specific rejections of a wide variety of heresies. In this confession Bullinger presented the Reformed truth, insisting that the Gospel he taught was the true, ancient religion revealed by God: “And although the teaching of the Gospel, compared with the teaching of the Pharisees concerning the law, seemed to be a new doctrine when first preached by Christ (which Jeremiah also prophesied concerning the New Testament), yet actually it not only was and still is an old doctrine (even if today it is called new by the Papists when compared with the teaching now received among them), but is the most ancient of all in the world. For God predestinated from eternity to save the world through Christ, and he has disclosed to the world through the Gospel this, his predestination and eternal counsel (II Timothy 2:9f.). Hence it is evident that the religion and teaching of the Gospel among all who ever were, are and will be, is the most ancient of all. Wherefore we assert that all who say that the religion and teaching of the Gospel is a faith which has recently arisen, being scarcely thirty years old, err disgracefully and speak shamefully of the eternal counsel of God” (chapter 13).2

In the Second Helvetic Confession and in all his work, Bullinger expressed the faith which he regarded as biblical, ancient and catholic—the faith reformed in the sixteenth century according to the Word God. He was a faithful and diligent servant and confessor of Jesus Christ.

(Part II – Heinrich Bullinger: Christian Confessor to be continued in the November/2000 issue of The Outlook)

Footnotes

1 See for example]. Wayne Baker, Heinrich Bullinger and the Caverumt The Other Reformed Tradition, Athens, Ohio (Ohio University Press), 1980.

2 Quotations from the Second Helvetic Confession are taken C. Cochrane, from Arthur ed., Reformed Confessions of the 16th Century, Philadelphia (Westminster Press), 1966.

Dr. W. Robert Godfrey, professor of Church History, is also president of Westminster Theological Seminary in Escondido, CA. He is a contributing editor of The Outlook Magazine.