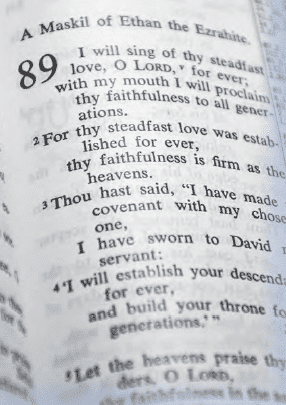

Although Psalm 89 is in the genre of “laments,” it nonetheless reveals much about God’s steadfast love to a needy, sinful people. In this Psalm, the Lord takes great care to show how He will not abandon His people. He shows this in His word, His oaths, His might, and in the promise of future redemption. Finally, in swearing an oath on His holiness, God gives surety that He cannot ever abandon His people. No matter how greatly they transgress, He will bring them back to Himself.

Scripture entreats us to view our relationship with God in terms of covenants. God is a covenant-keeping God. He relates to mankind through covenants. From the beginning of time God has entered into covenants with man. The first such covenant was “a covenant of works, wherein life was promised to Adam, and in him to his posterity, upon condition of perfect and personal obedience.” The Lord also blessed certain individuals, such as Abraham, with covenant relationships. Psalm 89 is primarily concerned with the covenant God made with Abraham’s son, David. It is to this covenant that the prophet most often appeals.

This Psalm is filled not only with outright references to the covenant, but with covenant language such as the Hebrew word hesed (cf. verses, 1, 2, 14, 24, 28, 33, 49), often translated “lovingkindness,” “mercy,” or “steadfast love.” Sinclair Ferguson writes of hesed, “it means God’s deep goodness expressed in his covenant commitment, his absolute loyalty, his obligating of himself to bring to fruition the blessings he has promised, whatever it may cost him personally to do that.” Based on the language used by the prophet in this psalm, it is clear that the prophet had a similar understanding of hesed, which is why there are so many references to God’s faithfulness (cf. verses, 1, 2, 5, 8, 14, 24, 33, 49). God’s faithfulness and steadfast love are bound up together: God is faithful because of His steadfast love, and He has steadfast love because He is faithful.

The psalmist begins this lament with the beautiful praises of God’s long established mercies and blessings. This lament shows the prophet’s trust in God. Although he and his nation are greatly afflicted, he nonetheless is still moved to praise God’s mercy of old, assured that one day the tangible manifestations of that distinct mercy will be visible again to the covenant people.

In verses 3–4 the prophet introduces the covenant God made with David, the mediator through whom this prophet makes his appeal. In these verses, we see that the foundation of his faith is the Word of the Lord. Calvin writes, “Faith ought to depend on the Divine promise,” which gives the reader more confidence in the authority of the prophet’s appeal. The confidence is not in God’s word to the prophet alone, but God’s word to him through David—a covenant mediator—for the people of geopolitical Israel.

The covenant with David was but a shadow of God’s covenant with Christ. David represents Christ, who is the ultimate covenant Mediator. God’s covenant with His people through Christ allows the church to go to the Father and ask blessings. So here, too, the psalmist came expecting God’s grace because of God’s word to David. When the New Testament saint prays, he follows his Lord’s command to pray “in Jesus’ name,” because Christ is the ultimate covenant Mediator for the church. Prayers not offered through and in Christ’s name are abominations to God. So too, in this revelation of God’s covenant, the Old Testament saint prays for the sake of the most immediate covenant mediator, David, who is a type of Christ.

The saint knows that, although times may be hard at present, God will keep His covenant with David. This confidence moves him to song and is the reason for the persistent joy he has through affliction. The everlasting nature of this covenant is cause for great thanksgiving because the prophet knows it points to a new type of David, one who could truly have an everlasting reign: namely Jesus Christ. The saint sings in expectation of that promised deliverer.

After confessing his faith and its foundation, the psalmist recites God’s greatness and tells of His wonders. He begins by praising God for his wonders, but the exaltation is chiefly praise for God’s steadfastness. This mighty God is also faithful. These verses serve as an introduction to the next fourteen verses, which praise God’s deeds, tokens of His faithfulness. In verses 9–10, the psalmist gives an example of that mighty faithfulness displayed, recalling God’s sovereignty over the sea and His destruction of Rahab. Calvin sees these verses as referring to the Exodus, with Rahab representing Egypt.

In verse 14, the psalmist takes us into God’s sanctuary to view the very foundation of God’s throne. The ornaments of Jehovah’s throne and reign are not those of an earthly potentate, but the very attributes of His character, alone more grand than any earthly prince: “righteousness and justice.” Earthly magistrates must adorn their throne with foreign objects to give the appearance of majesty, but Jehovah is by His nature more majestic than they. The psalmist does not stop only at God’s righteous justice, for He is ever preceded by two other attributes, “steadfast love and faithfulness.” The Father is not only an all-powerful, perfectly righteous judge, but also full of mercy and longsuffering concern for His people. God’s mercy and His justice meet together in the person of Christ. Christ was sent to show God’s mercy to bring His unfaithful people to Himself, and to bear the just punishment upon Himself. Righteousness and justice kiss steadfast love and faithfulness on the cross at Calvary.

After recounting the joys of membership in the covenant community, the prophet considers the covenant with David. The psalmist again and again emphasizes God’s choice, for since this covenant rests not on the merits of the chosen, but purely on the grace of God, it is everlasting. At first glance, it may appear that God chose the mighty, but it quickly becomes clear that the mighty one is only great because God has “granted,” “exalted,” “found,” and “anointed” him. David, whom He chose, was not great and powerful but the weakest of his brothers. There was nothing of royalty in David or in any whom God chooses. God’s wisdom is unfathomable to men; it is like the wind blowing where it wishes. In the same way, we do not know how or why God chooses whom He will. Because of this, our only response must be gratitude, not second guessing God’s grace or justice. Calvin clarifies that this covenant with David does not supersede the Abrahamic covenant, but rather strengthens it and carries it “forward by a continued process of improvement” ultimately in Christ.

After praising the Author of this covenant, the psalmist recounts God’s promises of blessing for David and His people. God promises David aid from the wicked and the increase of his reign and honor. Though at times David’s line would be cut down, a root always remained until the coming of Christ. Because of Christ, these blessings can be assured to David and the church at large. Christ’s victory outwitted the enemy; Christ crushed his foes and struck down the adversary of His church. Christ’s Kingdom extends even beyond the “sea” and the “rivers” (cf. vs. 25, Ps. 72:8). In fulfillment of David’s Kingdom, the church has citizens from every tribe and nation on the earth adopted into God’s family.

The great victory that allowed these gracious kisses of God did not come, however, without great cost. In the very manner in which God the Father exalted His people, God—incarnate as the Son—lowered Himself. First, God declares: “My arm also shall strengthen Him.” Christ went willingly to the cross, weak, as a lamb led to the slaughter. For the transgressions of David, Abraham, and all His covenant people, God withdrew His arm and allowed Christ to be wounded, smitten, stricken, and afflicted. Such was the faithfulness of God to His whoring people, that He would come to them and bear their sins and credit His righteousness to them.

Second, “the enemy shall not outwit him.” Day after day, Christ taught in the temple, yet none of the legalists dared touch Him, for fear of the people. Instead, the priests plotted with one of His twelve to outwit and capture Him in an orchard outside the city. His enemy thought he could deceive Him, but even this was comprehended in God’s infallible foreknowledge. Our Lord allowed Himself to be captured by the enemy so that the blessings of David might be possible, God’s word fulfilled, and His people ransomed. The Devil thought he could outwit the Lord, but Christ triumphed over him, though to all the scoffers (cf. Ps. 1) it appeared as though they had outwitted Him.

Third, “the wicked shall not humble him.” Christ, the second person of the Trinity, abandoning His glory, came to earth and took on the very form and infirmities of man. He not only became a man of sorrows, living a life as a humble sojourning preacher, but He was exposed to shame, spitting, and scoffing by the wicked at His death. Those who hated Him struck Him down and murdered Him.

Fourth, “I will crush his foes before him.” It was the will of God to “crush” Christ for the iniquity of His people. He brought down the full measure of His wrath and condemnation upon our Lord, the full measure which we deserved. The Father crushed His own Son that we, His foes, may be reconciled to Him.

With the fullness of Scripture, we can see the vastness of God’s grace, mercy, and steadfast, covenant love displayed for all to see: bleeding, dying, afflicted on a cross, set on a hill used to execute the most egregious of criminals. There, for mercy’s sake, once and for all, Christ, Himself fully God, fully Man, fully Righteous, took on the sin “of many” that they may be forgiven and have life in the covenant. But even without the completion of God’s special revelation, the prophet knew God would keep His people. He ends this section with God’s promise that His covenant will stand and establish David’s offspring forever. These promises, by design, precede the saint’s retelling of the “covenant curses” on David’s line, to serve as an introduction to what follows.

After the psalmist recounts the promises of God and the blessings of God to the church through the covenant mediator, he turns to address a more immediate situation. In verses 30–37, the psalmist shows God’s concern to keep His people from rejoicing in sin. God, knowing that the “posterity of David . . . would frequently fall from the covenant, by their own fault, has provided a remedy . . . in His pardoning grace.” Not only has He provided a remedy, He does not allow them to continue in their sins, and promises chastisements that they may learn to follow Him and not delight in sin.

When the results of their sins come down upon them, His people learn to see the beauty of God graciously giving His statutes. Through the misery, they see the horrid nature of their sin, which drives them to their Redeemer. Even affliction is a sign of His grace for it drives them back to Him, away from their sin. Through the trouble, they see their need for Christ’s righteousness all the more and are humbled anew, seeing that the “salvation of the church depends solely upon the Grace of God and the truth of His promises.” God uses affliction to drive His people back to Him; though He “punish[es] their transgression with the rod and their iniquity with stripes” (vs. 32), His punishment does not consume them. The Son bore the full measure of God’s wrath, so that the people of God might only be chastised and not smitten, for by the Son’s stripes we are healed.

The prophet dwells briefly on the chastisement, but then returns to considering God’s faithfulness, for it alone endures. In the strongest words possible, the psalmist retells God’s faithfulness despite affliction. He recounts the Lord’s strongest oath, upon His holiness, that He will be faithful to David. God’s oath will not change. He swears not only by mere created things, but makes a covenant with David founded in Himself on His own holiness. To allow even one member of David’s line, the church, to fall away would be to impugn God’s honor and His holiness. For that reason, with His Son before Him pleading mercy (vs. 36), God ensures that all heirs of this covenant persevere to the end. This covenant is a shadow of the glorious covenant between the Father and the Son, which accomplishes our redemption, that Christ would redeem a people by shedding His blood for them.

After making it clear that he knows God’s word, God’s faithfulness, and the demands of God’s covenant, the prophet moves to the reason for his prayer: the affliction of the church. The saint does not begin this prayer as one would think, “O Lord have pity on us in this our hour of need. . . .” Instead, he cries out to God in familiarity, as a Father, “You have renounced the covenant with your servant!” It appeared as though God had renounced the covenant, since the blessings ceased. God was the source of immediate blessings, but God was also the source of immediate and temporal covenant curses for transgressions. The church was in the dust, overrun by her enemies. The saint has completely changed his tune, from Newton to Nietzsche. The change is so complete that it does not make logical sense, at first reading.

Either the saint has forgotten the entire psalm up to this point and calls God a liar, or this saint structured his prayer in such a way as to provide a comforting assurance of God’s steadfast faithfulness before making his complaint known. These accusations give the appearance that all things are going contrary to the divine promise. When we consider the whole psalm, we see that the saint prays to God knowing that He did not renounce the covenant, for he knows God will not and cannot. This section follows a declaration that, when the church sins, God will send affliction. Now that the saint has acknowledged the justice of God’s chastisement, he pleads with God to restore Israel’s fortunes.

It is a further sign of God’s graciousness that the saint approaches God, not with bitterness, but with a heavy heart and with clear, specific complaints and lamentations, knowing that God will hear him. He began by singing of the steadfast love of the Lord. The prophet clearly understands God to be gracious, despite what he may feel; by the assurance of God’s own words. He knows God will not cast off His people because he has just read it in the Word of God. Although he is not afraid to bare his feelings to God, his feelings are restricted and controlled by what he knows from God’s Word.

Even if the calamities had not been sent upon Israel, there is still the problem that man will someday die. He confesses the utter worthlessness of life apart from God and pleads with Him to show mercy and to end His wrath. Herein the saint reaches his climax; in verse 48 he cries out for a deliverer. He confesses the need for one not only to deliver man from hardship, but from the very power of death itself.

Paul writes in I Corinthians 15 that the blood of Jesus Christ alone can unite God and man. In Him, death is swallowed up in victory. Because of Christ, death has no sting and sin has no power over God’s people. Christ has won the victory, and God counts the church as victorious with and through Christ. Throughout the psalm, the psalmist has pointed to Christ through shadows and now claims Him plainly for all to see. The psalmist sees that all these promises are vanity and fleeting without one who can deliver man from hell’s power. At this verse, the psalmist seemingly cries out, “send us the Christ; send us your Messiah!” In this verse, the prophet exclaims the truest and deepest need of Israel, not that her walls be rebuilt, but that her people be saved from death. And that is the essential need that all people have.

Now that he has confessed Christ and his utter need of Him, there little left to say, and the psalmist moves to a recapitulation. He pleads for a return of the “steadfast love of old” and calls to mind the suffering of God’s people. He does so in a different manner now that He has made his profession of the Messiah. He tells the Father that the insults against the church are not simply against the saints, but mock the very footsteps of the promised Christ, who would deliver Israel to perfect peace and blessedness with the Father.

The saint ends with simple trust: “Blessed be Jehovah forever!” With his mature faith, he knows there is nothing left to say, but to trust in God’s faithfulness and sovereignty. He rejoices in affliction because of the promises of God, ending his lament with a doxology and to “assuage the greatness of his grief in the midst of his heavy afflictions, that he might entertain the livelier hope of deliverance.” From this Psalm, we see, first, the importance of frequent, fervent, and familiar prayer. The saint can cry to God in such a manner because he knows his Father. He is frequently in prayer. Also apparent is that he is regularly reading the Scripture, the book of the covenant. Fervent, effectual prayer is tied to a regular, close reading of the Scripture, for how else do we know what to pray. This psalm is the result of the Spirit’s working through one who is frequently in the Word of God and frequently in prayer.

Second, we learn that in time of trouble and affliction, the saints must look to God’s Word and not to their own feelings. As the hymnist writes, “When all around my soul gives way, He then is all my hope and stay.” We ought not to view a “frowning providence” as testimony that we have been cast off. In the Scriptures, the saint finds his assurance that God is with him through the difficult times and learns how to live his life and turn in repentance from sin, by prayer and petition. The reading of Scripture in times of affliction affects the prayers of the afflicted, for in it one learns how to pray and sees God’s promises of faithfulness.

Third, the attitude of a Christian ought to be naught but gratitude, trust, and humility before the righteous God. Were it not for God’s faithfulness, God’s concern for His holy honor, every article of the covenant with Abraham, Moses, and David would be trampled in the dust by the church’s pursuit of other gods. Instead, God pursues His people and causes them to return to Him and turn from their sin, imputing Christ’s righteousness to them in His grace. From this we see the necessity of Christ. Our security in the covenant is only because of His work; we may only appeal to the Father through Christ as Mediator because He alone can come to us, taste death for us, and rescue us from its power.

Finally, God can never cast off His chosen. Christ’s work is the security of the saint’s salvation. God will never lose him. Though the evil one will attempt to deceive and convince the saint that God has forgotten him, it is the Father’s great concern for His people to know that He will not forsake them. He will bring His people unto Himself to cause them to return to Him. God’s promise is founded in His holiness and guaranteed by the blood sacrifice of His Son. He will be faithful to complete the work He began; He cannot forget His dear ones, whose names are written, even engraved on the palms of His hands.

————————

1. Westminster Confession of Faith (1646), 7.2.

2. Sinclair B. Ferguson, Faithful God, (Bryntirion, Wales: Bryntirion Press, 2005), 64. (emphasis original)

3. John Calvin, Calvin’s Commentaries, vol. 5, “Commentary on the Book of Psalms: Volume Second” (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2005), 421

4. Calvin, 426

5. Also consider Matthew 5:2–12

6. Robert Lewis Dabney, The Five Points of Calvinism (Richmond, VA.: Presbyterian Committee of Publications, 1895; Harrisonburg, VA: Sprinkle Publications, 1992), 53. citations are to the Sprinkle edition

7. Calvin., 434

8. Calvin, 441.

9. Calvin, 459.

Mr. Ryan Biese is a graduate of Grove City College in Pennsylvania. He plans to attend Reformed Theological Seminary in the fall.